The COTs never had a chance.

There are regular TIO reports on the progress of the CoT claims.

Senate Hansard information dated 26th September, 1997 (GS-CAV Exhibit 89 to 154(b) - See GS-CAV 124-B) confirms that:-

Ted Benjamin, Telstra’s main arbitration defence liaison officer in Graham and Alan’s arbitrations, was also a member of the TIO Council and

During a Senate hearing into COT issues, the then-new TIO, John Pinnock, agreed that Mr Benjamin had not removed himself from council discussions of COT matters:-

Senator SCHACHT – “Mr Benjamin, you may think that you have drawn the short straw in Telstra, because you have been designated to handle the CoT cases and so on. Are you also a member of the TIO Board?”

Mr Benjamin – “I am a member of the TIO council.”

Senator SCHACHT – “Were any CoT complaints or issues discussed at the council while you were present?”

Mr Benjamin – “There are regular reports from the TIO on the progress of the CoT claims.”

Senator SCHACHT – “Did the council make any decision about CoT cases or express any opinion?”

Mr Benjamin – “I might be assisted by Mr Pinnock.”

Mr Pinnock – “Yes.”

Senator SCHACHT – “Did it? Mr Benjamin, did you declare your potential conflict of interest at the council meeting, given that as a Telstra employee you were dealing with CoT cases?”

Mr Benjamin – “My involvement in CoT cases, I believe, was known to the TIO council.”

Senator SCHACHT – “No, did you declare your interest?”

Mr Benjamin – “There was no formal declaration, but my involvement was known to the other members of the council.”

Senator SCHACHT – “You did not put it on the record at the council meeting that you were dealing specifically with CoT cases and trying to beat them down in their complaints, or reduce their position; is that correct?”

Mr Benjamin – “I did not make a formal declaration to the TIO.”

10. Telstra's CEO and Board have known about this scam since 1992. They have had the time and the opportunity to change the policy and reduce the cost of labour so that cable roll-out commitments could be met and Telstra would be in good shape for the imminent share issue. Instead, they have done nothing but deceive their Minister, their appointed auditors and the owners of their stockÐ the Australian taxpayers. The result of their refusal to address the TA issue is that high labour costs were maintained and Telstra failed to meet its cable roll-out commitment to Foxtel. This will cost Telstra directly at least $400 million in compensation to News Corp and/or Foxtel and further major losses will be incurred when Telstra's stock is issued at a significantly lower price than would have been the case if Telstra had acted responsibly.

11. Telstra not only failed to act responsibly, it failed in its duty of care to its shareholders. So the real losers are the taxpayers and to an extent, the thousands of employees who will be sacked when Telstra reaches its roll-out targetÐcable past 4 million households, or 2.5 million households if it is assumed that Telstra's CEO accepts directives from the

Did Telstra covertly eavesdrop on my phone conversations with two different clinical psychologists, with whom I confided the deep-rooted trauma of living with the betrayal by China and North Vietnam? I entrusted the names of these professionals to the Australian Federal Police (AFP) after the government regulator, AUSTEL, revealed that Telstra had been secretly monitoring my service lines—without my consent or even my knowledge → Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1)

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

Hovering your cursor or mouse over the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp image above will lead you to a document dated March 1994, referenced as AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings. This document confirms that government public servants investigating my ongoing telephone issues supported my claims against Telstra, particularly between Points 2 and 212. It is evident that if the arbitrator had been presented with AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, he would have awarded me a significantly higher amount for my financial losses than he ultimately did.

Government records (see Absentjustice-Introduction File 495 to 551) show AUSTEL's adverse findings were provided to Telstra (the defendants) one month before Telstra and I signed our arbitration agreement. I did not receive copies of these same findings until 23 November 2007, 12 years after the conclusion of my arbitration, which was outside the statute of limitations for me to use those government findings to appeal the arbitrator's award.

AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, dated 4 March 1994, confirmed that my claims against Telstra were validated (see points 2 to 212 in that report). Unfortunately, I did not receive a copy of these findings until November 23, 2007, 12 years after the termination of my arbitration process. Moreover, the government officials had already validated my claims as early as March 4, 1994, six weeks before April 21, 1994, when I signed the arbitration agreement.

But despite that, I was still required to pay over $300,000 in arbitration fees to prove something the government had already established in my case, that Telstra was still not meeting their General Carriers licensing conditions in regard to my service lines at the time the arbitrator Dr Gordon Hughes stopulated in his award findings that Telstra had met those continues after July 1994 as point 2.23 (h) in his award states.

In straightforward terms, AUSTEL (now known as ACMA) failed in its legal obligations to me by not directing the arbitrator to modify his decision until Telstra could demonstrate compliance with its licensing conditions. The attached evidence, Chapter 4: The New Owners Tell Their Story, shows that Telstra was still not meeting those licensing conditions as recently as November 2006, nine years after the arbitrator prematurely issued his findings.

What is important to add here is that the Candadian Prinipal technical advisor, Paul Howell, in his 30 April 1995 formal report, advised Dr Gordon Hughes (the arbitrator) that:

“One issue in the Cape Bridgewater case remains open, and we shall attempt to resolve it in the next few weeks, namely Mr Smith’s complaints about billing problems.

“Otherwise, the Technician Report on Cape Bridgewater is complete.” ( Open Letter File No/47-A to 47-D)

and

“Continued reports of 008 faults up to the present. As the level of disruption to overall CBHC service is not clear, and fault causes have not been diagnosed, a reasonable expectation that these faults would remain ‘open’,” (Exhibit 45-c -File No/45-A)

As of 2026, Dr Hughes has not provided any explanations regarding why he and his technical consultants failed to diagnose the issue. Additionally, he has not addressed the issue of my two service lines being locked, which was causing my ongoing billing issues.

On 27 January 1999, after having also read my first attempt at writing my manuscript absentjustice.com, the same manuscript I provided Helen Handbury, Sister to Rupert Murdoch, Senator Kim Carr wrote:

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

It is now 2026, and the Australian Federal Police AFP has still not disclosed to me why Telstra senior management has not been brought to account for authorising this intrusion into my business and private life, regardless of Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stating:

"No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks."

It is most important that we raise the statement made in a Telstra internal email that is discussed on this website absentjustice.com noting:

"The sensitive papers referred to above, dated 23 August 1993, of which Telstra’s corporate secretary claimed, “Nothing in these documents to cause Telecom any concern in respect of your case,” actually provided clear evidence that Telstra’s management had recorded a telephone conference I had with the former prime minister of Australia Malcolm Fraser in April 1993, although what I had discussed with Mr Fraser had been redacted (blanked) out).

The Weight of Treachery

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

Leading up to the signing of the COT Cases arbitration, on 21 April 1994, AUSTEL wrote to Telstra on 10 February 1994 stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

This internal, dated 25 February 1994, is a Government Memo confirming that the then-Minister for Communications and the Arts had written to advise that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (AFP Evidence File No 4)

The fax imprint across the top of this letter is the same as the fax imprint described in the Scandrett & Associates report (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), which states:

“We canvassed examples, which we are advised are a representative group, of this phenomena .

“They show that

- the header strip of various faxes is being altered

- the header strip of various faxes was changed or semi overwritten.

- In all cases the replacement header type is the same.

- The sending parties all have a common interest and that is COT.

- Some faxes have originated from organisations such as the Commonwealth Ombudsman office.

- The modified type face of the header could not have been generated by the large number of machines canvassed, making it foreign to any of the sending services.”

The fax imprint across the top of this letter, dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the January 1999 Scandrett & Associates report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations. One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

It is clear from exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

Does Telstra expect the AFP to accept that, every time this officer left the Portland telephone exchange, the alarm bell set to broadcast my telephone conversations throughout the exchange was turned off? What was the point of setting up equipment connected to my telephone lines that only operated when this person was on duty? When I asked Telstra under the FOI Act during my arbitration to supply me all the detailed data obtained from this special equipment set up for this specially assigned Portland technician, that data was not made available during my 1994.95 arbitration and has still not been made available in 2026.

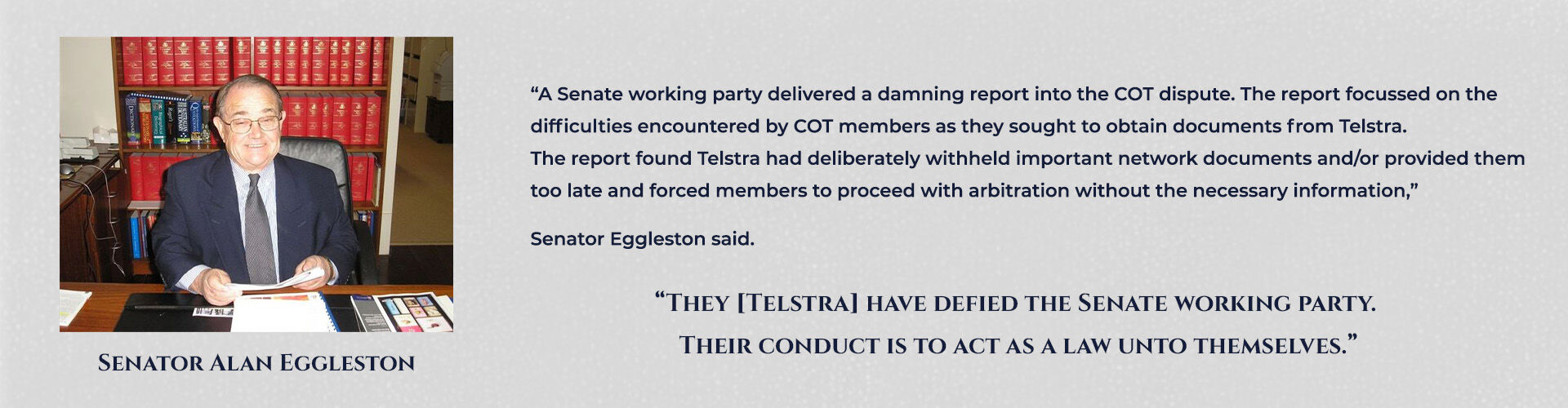

On 23 March 1999, after most of the COT arbitrations had been finalised and business lives ruined due to the hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees to fight Telstra and a very crooked arbitrator, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Hover your mouse over the following six senators highlighted below which takes to the Australian Senate

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston → Sen Richard

These six senators all formally record how those six senators believed that Telstra had ‘acted as a law unto themselves’ throughout all of the COT arbitrations, is incredible. The LNP government knew that not only should the litmus-test cases receive their requested documents but so should the other 16 Australian citizens who had been in the same government-endorsed arbitration process → An Injustice to the remaining 16 Australian citizens

Dreams Betrayed

Owning the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp should have been the fulfilment of a cherished childhood dream. I envisioned laughter echoing through the halls, families gathering for holidays, and the satisfaction of building something enduring in the hospitality industry. Instead, almost from the first week, I was confronted with a sinister silence — phones rang without connecting, and customers were met with dead lines or recorded messages claiming the number was not in service.

The joy of welcoming guests morphed into a relentless cycle of frustration. Suppliers reported they could not reach me, essential faxes evaporated into thin air or returned blank, and clients resorted to writing letters through Australia Post to tell me they could not get through. Seventy‑six of these letters were forwarded to the government communications authority as evidence of the issues I faced, as my Letter of Claim → CAV P3- Exhibit 8- Exhibit 9 shows.

What should have thrived was slowly strangled by faults Telstra refused to acknowledge. Each time I reported the issue, the response was chillingly identical: “No fault found.” My livelihood was collapsing under the weight of a communication network that had become utterly unreliable. What began as a dream of hospitality and community was cruelly betrayed by negligence and deceit, leaving me to fight for survival in a business suffocated by silence.

The Farce of Arbitration

When the government finally consented to arbitration, I allowed myself a glimmer of hope that justice might be within reach. Instead, the process unfolded as a sordid charade, designed to protect Telstra and bury our claims beneath layers of obstruction. Evidence was systematically withheld or delivered in such a delayed and heavily censored manner that it was rendered meaningless. Vital conversations were intercepted, crucial faxes vanished, and documents were fabricated to suit Telstra’s agenda.

The arbitrator ignored the core issues of my claim, no matter how persistently I raised them. Regulators stood idly by, impotent in the face of corporate malfeasance, while ministers who had once promised support turned their backs upon assuming power. It became alarmingly clear that the arbitration was not a quest for fairness — it was a deliberate attempt to silence dissent.

Telstra approached me as if I were a common criminal, wielding every tactic to delay, confuse, and exhaust me. What should have been a straightforward assessment of proven faults spiralled into a costly, protracted ordeal. The very system established to deliver justice had transformed into a theatre of injustice, where rules were bent, evidence was tampered with, and accountability was brutally erased.

What emerged was not merely a breakdown of telecommunications but a profound erosion of trust in the institutions meant to safeguard citizens. This arbitration was not just a farce; it revealed a darker truth: unchecked corporate power, shielded by government complacency, has the capacity to turn ordinary lives into battlegrounds, shrouded in treachery and deceit.

Freehills Hollyndale & Page / Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne.

The matter at hand raises an important question: Does Herbert Smith Freehills in Melbourne recognize a moral and ethical responsibility to clarify to the Australian government why their company, which was previously known as Freehills Hollyndale & Page, provided false information to Mr. Ian Joblin during my arbitration proceedings, as well as to the Senate in the year 1997? This false information was submitted despite the Senate explicitly requesting confirmation about the validity of my claims. Such an act of deception directed at a Senate Committee—especially as highlighted in the context of Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2—can be categorised as contempt of the Senate, a serious offence that undermines the integrity of governmental processes.

During this same arbitration, I endured a relentless barrage of corrupt practices that not only decimated my business but also drew the unwanted attention of government authorities. It is nothing short of shocking that, five months after the arbitrator delivered his ruling declaring that there were no ongoing issues affecting my business as point 3.2 (h) in his findings, the government communications authority AUSTEL (now called ACMA) allowed Telstra to sweep in and illegally resolve these unresolved arbitration billing issues in a clandestine meeting on October 16, 1995 (See Absent Justice Part 2 - Chapter 14 - Was it Legal or Illegal)?

This duplicitous intervention obliterated my legal right to reply to Telstra's response to my arbitration claims, rendering me powerless as AUSTEL/ACMA, supposedly representing the government’s interests, turned a blind eye to the truth. They granted Telstra the ability to respond to my unresolved claims in secret, effectively silencing me when I needed a voice the most. The misuse of the Confidentiality Agreement by all parties involved is an outright betrayal; it serves as a shield for their corruption, allowing them to evade accountability while I am left to battle the overwhelming evidence of their deceit.

This egregious manoeuvring has inflicted thirty years of anguish on my partner and me, revealing a deeply sinister conspiracy that has eroded trust and justice. What should have been a fair process has descended into a dark realm of manipulation and injustice, leaving us grappling with the devastating consequences of their greed and betrayal.

You can learn more about the deceptive conduct of the arbitrator, Dr. Hughes, as well as the administrator of my arbitration, John Pinnock, who was also involved in this deception as the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, along with John Rundell, the Arbitration Project Manager. For further details, click on Major Fraud Group Victoria Police, which is also discussed below.

• falsified technical reports• intercepted communications• withheld evidence• compromised arbitrators• government regulators who looked the other way• and a corporate giant determined to silence the truth

• how Telstra manipulated evidence• how government‑endorsed arbitration became a weapon• how whistleblowers were silenced• how truth was buried under layers of bureaucracy• and how ordinary Australians were sacrificed to protect corporate interests

It is a warning — and a testament to the resilience of someone who refused to be erased.If you believe in accountability…If you believe in justice…If you believe that truth still matters…

This was not administrative chaos. It was a pattern.

Telstra and its lawyers withheld approximately 150,000 FOI documents from the COT Cases during the 1994–1996 arbitrations. These documents — critical, time‑sensitive evidence — were only released to five of the twelve COT Cases in 1998, and only because the Senate forced Telstra’s hand. Such conduct was not accidental. It was a strategic obstruction.

It was corruption — calculated, deliberate, and devastating. On 26 September 1997, Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman John Pinnock formally addressed a Senate estimates committee refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D). He noted:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

There is no amendment attached to any agreement, signed by the first four COT members, allowing the arbitrator to conduct those arbitrations entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedure – nor was it stated that he would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. How can the arbitrator and TIO continue to hide under a confidentiality clause in our arbitration agreement when that agreement did not mention that the arbitrator would have no control because the arbitration would be conducted entirely outside the agreed procedure?

In October 1997, Telstra submitted the Cape Bridgewater/Bell Canada International Inc (BCI) report in response to inquiries posed by the Senate. At that time, Telstra was fully aware that the information contained in that report was inaccurate. Despite this knowledge, the company has faced no repercussions for its actions, which many argue constituted a clear contempt of the Senate by providing intentionally misleading information (as referenced in (see Scrooge – exhibit 62-Part One – Sue Laver BCI evidence and Scrooge – exhibit 48-Part Two – Sue Laver BCI Evidence)

To illustrate the severity of the situation, I reflect on my own circumstances. Had I, in 1997, dared to reveal the truth about Telstra’s unethical corporate practices—practices that the Senate was aware were legitimate violations—I would have faced the possibility of imprisonment. Yet, when Telstra itself supplied false information about the telephone exchanges to which my business was connected, they were remarkably not held accountable for their contempt toward the legislative body. This profound disparity in accountability raises serious questions about corporate ethics and the integrity of our regulatory systems.

This underhanded tactic stripped me of my legal right to challenge Telstra's submission, while Dr Hughes, the arbitrator, had already issued his findings in Telstra's favour, deceitfully claiming that my business had not suffered ongoing problems after July 1994.

Was he completely unaware of the ongoing billing issues affecting my business, or was he involved in hiding these systemic problems? These billing issues raised concerns for Mr Neil Jepson, the barrister for the Major Fraud Group, as the archive files of the Major Fraud Group would show.

At point 3.2 (h) in his award, Dr Hughes notes: "The claimant adds that he continued to suffer transmission problems after March 1993, although since July 1994 he has had relatively little cause for complaint".

This statement at point 3:2,(h) in Dr Hughes' formal awar,d does not match the statement made by his official technical consultants DMR & Lane in their 30 April 1995 formal findings at 2.23, which state:

“One issue in the Cape Bridgewater case remains open, and we shall attempt to resolve it in the next few weeks, namely Mr Smith’s complaints about billing problems.

“Otherwise, the Technician Report on Cape Bridgewater is complete.” ( Open Letter File No/47-A to 47-D)

and

“Continued reports of 008 faults up to the present. As the level of disruption to overall CBHC service is not clear, and fault causes have not been diagnosed, a reasonable expectation that these faults would remain ‘open’,” (Exhibit 45-c -File No/45-A)

The Evidence Dr Hughes Refused to Examine

AUSTEL’s Mr Kearney made it plain in his February 1996 report (see ) that my arbitration claims were valid. His conclusions were drawn directly from the five volumes of technical evidence that Dr Gordon Hughes refused to allow his own two arbitration consultants the extra time they requested to assess. Kearney’s findings were unequivocal: the faults I had documented were still present in Telstra’s network as late as 13 January 1995.

The twenty‑three examples he identified demonstrated that Telstra’s late submission to AUSTEL on 16 October 1995 was fundamentally flawed. In fact, without my agreement for AUSTEL to send Mr Kearney on a twelve‑hour round trip from Melbourne to Cape Bridgewater to collect the material Dr Hughes had ignored, AUSTEL would never have discovered that Telstra’s October submission was a fabrication.

This is the critical point: the information Telstra was allowed to provide to AUSTEL in secret—without giving me my legal right of reply—did not align with Mr Kearney’s February 1996 findings. The two sets of information cannot be reconciled. One was grounded in evidence; the other was constructed to mislead.

It was these secret addresses of my arbitration claims by Telstra and the government communications authority that prompted Mr Neil Jepson to conclude that others in a higher position than those administering my arbitration were guiding my evidence away from investigation under the agreed rules of arbitration. These semantic billing problems were dynamite

Major Fraud Group Victoria Police

The link above to the Major Fraud Group at Victoria Police provides important information regarding my case. It details how, during an official arbitration investigation led by Laure James, the President of the Institute of Arbitration in Australia, Dr. Gordon Hughes (the arbitrator from my previous arbitration), John Pinnock (Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman and also the administrator of my prior arbitration), and John Rundell (the Project Manager appointed by the TIO) conspired to prevent Mr. James from uncovering the truth about my claims. They collectively undermined my credibility as an Australian and attacked my character by investigating issues that never occurred.

Anyone who reviews the more than 3,600 pieces of evidence available on the website absentjustice.com will likely conclude that I am a person of strong character. Unfortunately, the collective dishonesty of Dr Hughes, John Pinnock, and John Rundell prevailed, resulting in the termination of Mr James's investigation. I believe I deserve to have my character assessed based on my years of service as a merchant seaman

The Deal

The most disastrous deal ever struck by any government — a deal that treated its own citizens as little more than dart‑board targets — stands as a monument to failure. It was crafted not to heal old wounds but to drive the blade deeper, ensuring that past conflicts would fester rather than fade. Instead of offering reconciliation, it inflamed grievances that had already scarred generations, widening a rift of mistrust and animosity that may never fully close.

This ill‑conceived pact has become a bitter legacy, a stark reminder of how easily the pursuit of personal or political gain can descend into collective ruin. It shows, with painful clarity, what happens when those in power choose expedience over integrity, and self‑interest over the people they are sworn to serve.

Deleted Without Being Read: The DCITA Cover-Up

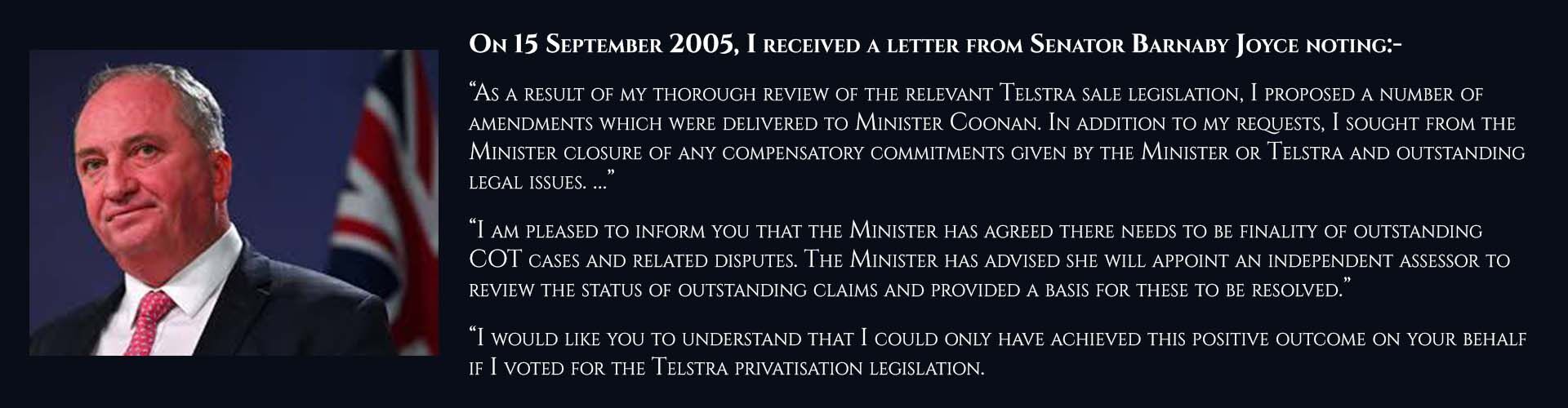

I hold two email receipts—dated 23 April and 25 July 2006—sent by my claims advisor, Ronda, to the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts (DCITA). These aren’t just technical records. They’re evidence of a disturbing pattern of deception. They demonstrate how my legitimate claims were systematically undermined, ignored, and ultimately erased from the process intended to protect me.

These emails were part of a government-endorsed process—one that Senator Barnaby Joyce publicly supported when he cast his critical vote in favour of Telstra's privatisation. Joyce had been assured that my claims would be assessed appropriately. That promise turned out to be hollow.

A Process Shrouded in Secrecy

From the beginning, the DCITA assessment was cloaked in secrecy. There was no transparency, no accountability. Then, in August 2006, the process was abruptly shut down—without explanation. Ronda Fienberg, my dedicated and loyal editor, received confirmation that her emails had been opened. But what’s truly chilling is that two critical items in my submission were never read. They vanished—deleted without being opened on 1 February 2008, more than 18 months after they were sent.

Two examples follow:

MESSAGES RECEIVED 1st February 2008, on behalf of Alan Smith:

Your message

To: Coonan, Helen (Senator) Cc: Lever, David; Smith, Alan Subject: ATTENTION MR JEREMY FIELDS, ASSISTANT ADVISOR Sent: Sun, 23 Apr 2006 17:31:41 +1100

was deleted without being read on Fri, 1 Feb 2008 16:56:36 +1100

ATTACHMENT:

Final-Recipient: RFC822; Senator.Coonan@aph.gov.au

Disposition: automatic-action/MDN-sent-automatically; deletedX-MSExch-Correlation-Key: sdD1TSUHx0CoTD0Qm4wBVw==oOo

Original-Message-ID: 001601c6669f$95736a00$2ad0efdc@Office

Your message

To: Coonan, Helen (Senator) Cc: Smith, Alan Subject: Alan Smith, unresolved Telstra matters Sent: Tue, 25 Jul 2006 00:00:42 +1100

was deleted without being read on Fri, 1 Feb 2008 16:56:23 +1100ATTACHMENT:Final-Recipient: RFC822; Senator.Coonan@aph.gov.au Disposition: automatic-action/MDN-sent-automatically; deleted X-MSExch-Correlation-Key: bNlMYfUKcUGqvIXiYQZULA==

Original-Message-ID: 003a01c6af21$2b7ece30$2ad0efdc@Office

“Hundreds of federal public servants were sacked, demoted or fined in the past year for serious misconduct. Investigations into more than 1000 bureaucrats uncovered bad behaviour such as theft, identity fraud, prying into file, leaking secrets. About 50 were found to have made improper use of inside information or their power and authority for the benefit of themselves, family and friends“

Therefore, I have relied on page 3 of the Herald Sun (22 December 2008), published under the blunt and telling headline “Bad Bureaucrats,” because it is short‑worded, direct, and impossible to misinterpret. It stands as further proof that Australia’s government public servants have, at times, behaved as a law unto themselves and must be held accountable for their misconduct. Were some of these "Bad Bueaucrats" chosen by the Liberal Coalition Government to assess the COT Cases 205/2006 DCITA claims?

"Beware The Pen Pusher Power - Bureaucrats need to take orders and not take charge”, which noted:“Now that the Prime Minister is considering a wider public service reshuffle in the wake of the foreign affairs department's head, Finances Adamson, becoming the next governor of South Australia, it's time to scrutinise the faceless bureaucrats who are often more powerful in practice than the elected politicians."

"Outside of the Canberra bubble, almost no one knows their names. But take it from me, these people matter."

"When ministers turn over with bewildering rapidity, or are not ‘take charge’ types, department secretaries, and the deputy secretaries below them, can easily become the de facto government of our country."

"Since the start of the 2013, across Labor and now Liberal governments, we’ve had five prime ministers, five treasurers, five attorneys-general, seven defence ministers, six education ministers, four health ministers and six trade Ministers.”

This article was quite alarming. It was disturbing because Peta Credlin, someone with deep knowledge of Parliament House in Canberra, has accurately addressed the issue at hand. I not only relate to the information she presents, but I can also connect it to the many bureaucrats and politicians I have encountered since exposing what I did about the China wheat deal back in 1967, and the corrupted arbitration processes of 1994 to 1998. These government stuff-ups and cover-ups have cost lives.

Senate Investigations and the BCI Deception

This chapter examines the significant errors that came to light during five Senate Estimates Committee investigations related to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, with a particular focus on the flawed Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) testing process. Deficiencies marked this process and, in my experience, proved to be impractical.

From 1994 until at least 2011, Graham Schorer, spokesperson for the COT Cases, consistently maintained a compelling belief. He recalled an unsettling phone call from computer hackers in April 1994. Among them, one prominent individual—whom we now suspect to be Julian Assange—used the term “report” when discussing documents and emails that allegedly exposed Telstra’s unlawful conduct.

"I can recall that during the period 2000/2001, I had arranged to meet Detective Sergeant Rod KURIS from the Victoria Police Major Fraud Squad at the foyer of Casselden Place, 2 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. At the time, I was assisting Rod with the investigation into alleged illegal activities against the COT Cases.

Rod then stated that he wanted me to follow him to the left side of the foyer. When we did this he then directed my attention to a male person seated on a sofa opposite our seat. He then told me that the person had been following him around the city all morning. At this stage Rod was becoming visibly upset and I had to calm him down. Rod kept on saying that he couldn't believe in what was happening to him. I had to again calm him down".

Points 21 and 22 in Mr Direen’s statement also record how, while he was a Telstra employee, he had cause to investigate “… suspected illegal interference to telephone lines at the Portland exchange,” but when he “… made inquiries by telephone back to Melbourne (he) was told not to get involved and that another area of Telstra was handling it” and that “... the Cape Bridgewater complainant was a part of the COT cases” (my Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp) business.

What remains unsettlingly unproven is the complicity surrounding the shadowy figures of Dr Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator, and Warwick Smith, the arbitration administrator. Both were fully aware that the Australian Federal Police were probing the very same phone and fax interception issues that Des Direen, representing Telstra, was investigating at the Portland Telephone exchange. These are not mere administrative oversights; they are deeply troubling matters that raise grave concerns about misconduct.

Continuity of Corruption: 2000–2025

Some people like to believe this corruption was confined to the past, resolved in the 1990s. They’re wrong. Between 2008 and 2011, the same practices continued: altered court documents, perjury, and even allegations of criminal activity within government ranks. In both State and Federal Parliament, betrayal runs rampant. Colleagues are destroyed through malicious falsehoods, just as claimants were destroyed during the arbitrations. The corruption didn’t end—it mutated.

The Human Cost

This wasn’t just about faulty Ericsson telephone equipment. It was about lives. My business was dismissed, my credibility undermined, and my livelihood jeopardised. Customers were left exposed to dangerous infrastructure while Telstra and government officials escaped accountability. The human cost of this betrayal is immeasurable.

The arbitration system failed because it was never truly independent. It was corrupted by political and corporate influence from the start. The COT Cases peeled back the layers, but the treachery has only deepened since. My role now is to document the truth, to ensure these betrayals are not forgotten, and to empower others to challenge the silence.

My struggle was never just about me. It was about whether democratic systems can be trusted to uphold transparency, fairness, and accountability. Canada’s handling of the Cape Bridgewater report, and Australia’s willingness to allow witnesses to be compromised, revealed a disturbing truth: when powerful interests are threatened, the rule of law bends. It delays. It ignores.

I urge you, my readers, to consider a disheartening reality: are we truly living under systems that safeguard the vulnerable while holding the powerful accountable? Or are we trapped in a web of corruption that masquerades as a legitimate process, where silence is presented as a resolution?BCI and SVT reports - Section One

As you scroll down the homepage, remember to hover your mouse over the images shown below.

Who hijacked the BCI and SVT Reports

The letter to the Federal Magistrates Court, dated December 3, 2008, reveals a troubling narrative involving Darren and Jenny Lewis, the new owners of my business since December 2001. After years of fighting against the negligence of the TIO and Telstra—who obstinately refused to test my business telephone lines despite ongoing issues first reported in February 1988—it became clear that something far more sinister was at play.

The arbitration process I underwent in 1994 was supposed to bring resolution, yet critical documents, notably the BCI and SVT test results for the Cape Bridgewater telephone exchange, vanished without a trace. Fast forward to 2008: copies of those very same results mysteriously disappeared again while being shipped to the Federal Court by the new owners.

How can we explain the uncanny repetition of document disappearances in two separate legal battles, fourteen years apart? It raises unsettling questions about corruption and treachery lurking within the very systems meant to protect us.

My letter to the Hon. David Hawker MP (see File 274 – AS CAV Exhibit 234 to 281] exposes a deeply unsettling truth: staff at the Portland Australia Post office were fully aware that certain mail leaving their facility could not be trusted to reach its destination. In that light, what possible purpose was served by mailing my arbitration documents to the arbitrator in 1994 and 1995? And why would the new owners of my business later submit critical Telstra‑related documents to the Federal Magistrates’ Court when there was every chance—every reasonable chance—that those documents would simply disappear into the void?

A letter dated 3 December 2008 from Darren and Jenny Lewis, the new owners of my business, echoed my concerns with chilling clarity. Their testimony underscored the same disturbing pattern I had witnessed years earlier. This was not a coincidence. This was not incompetence. This was something far more sinister.

What makes this even more unconscionable is the government’s silence—a silence so complete it borders on complicity. The accompanying image links show that the new owners were battling the very same phone problems I faced in 1988. Problems the arbitrator was supposedly tasked with resolving during my 1994–1995 arbitration. Yet here they were, still poisoning the business in 2008, still eroding its viability, still haunting my once beloved business, as the following link shows Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story

Such negligence does not happen by accident. It reeks of something darker—an entrenched treachery, a system where truth is disposable and duty is optional. It forces me to ask the question no honest citizen should ever have to ask: → Were there forces at work that prefer deceit over justice?

The key question is: Were these six sworn statements made under oath truthful or false? An honest response to this question could have significant implications, potentially affecting billions of dollars in Commonwealth spending and suggesting that Telstra misled the arbitrator to minimise its liability towards me. As demonstrated by the evidence, my phone issues persisted for eleven years after the arbitrator ruled in favour of Telstra, stating that they had resolved the network problems.

23 June 2015: Had the arbitrator appointed to assess my arbitration claims correctly investigated ALL of my submitted evidence, it would have validated my claim as an ongoing problem, NOT a past problem, as his final award shows. It is clear from the following link dated > Unions raise doubts over Telstra's copper network; workers using ... that when read in conjunction with Can We Fix The Can, released in March 1994, these copper-wire network faults have existed for more than 24 years.

9 November 2017: Sadly, many Australians in rural Australia can only access a second-rate NBN. This didn’t have to be the case: had the Australian government ensured the arbitration process it endorsed to investigate the COT cases’ claims of ongoing telephone problems been conducted transparently, it could have used our evidence to start fixing the problems we uncovered in 1993/94. This news article https://theconversation.com/the-accc-investigation-into-the-nbn-will-be-useful-but-its-too-little-too-late-87095, again, shows that the COT Cases' claims of copperwire ailing network were more than valid.

28 April 2018: This ABC news article dated 28 April 2018 regarding the NBN see >NBN boss blames Government's reliance on copper for slow ... needs to be read in conjunction with my own story going back 20 1988 through to 2025, because had the arbitration lies told under oath by so many Telstra employees had not occurred then the government would have been in a better position to evaluate just how bad the copper-wire Customer Access Network (CAN) was just 7-years ago.

The Final Insult

When I left Cape Bridgewater for the last time in February 2019, I carried the weight of decades of disillusionment. What began in March 1987 as a simple fight for a fair go had twisted into something far more sinister — a long, punishing struggle against a system that seemed determined to break me. The arbitration process, which should have delivered truth and justice, instead unfolded like a carefully staged performance, its outcome shaped long before I ever stepped into the ring.

Throughout that ordeal, seven Telstra employees stood before the arbitrator and swore that my business had always enjoyed the “world’s best rural telephone service.” Seven statements. Seven signatures. Each one felt like another layer in a web designed to obscure, confuse, and suffocate the truth. Two additional witness statements were made under oath, claiming that other customers had never experienced the phone issues I reported.

However, the government communications authority, AUSTEL, had already conducted its own investigation into my six‑year complaint. Their covert findings, completed in March 1994 and covering the very same unresolved telephone faults (see points 2 to 212 AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) left no room for doubt: the two additional sworn witness statements submitted by Telstra in their December 1994 arbitration defence were demonstrably false.

With those exposed, the tally rose to nine sworn statements that were found to be untrue. Nine Telstra employees—each one prepared to sign their name to false evidence—collectively worked to undermine my business, my livelihood, and my reputation, all to shield the interests of their employer, the government‑owned Telstra Corporation.

It was not an accident. It was a coordinated betrayal carried out under the protection of institutional power.

As we turned onto the ring road out of Portland, hoping to leave the nightmare behind, a towering billboard rose above the highway — a final, mocking reminder of everything I had endured.

Its message sliced through me like a blade:

“We’ve expanded Australia’s best network to Cape Bridgewater.”

There it stood, bold and triumphant, completely at odds with the sworn statements that had shaped my arbitration. The billboard, erected in 2018, cast a long shadow over the entire process. It felt like a public contradiction, a silent revelation that the narrative presented during arbitration had never aligned with the reality on the ground.

In that moment, the façade cracked. The contrast between what had been said under oath and what now loomed above the highway was impossible to ignore. It was a chilling reminder of how easily truth can be buried, how effortlessly a narrative can be shaped, and how deeply betrayal can cut when trust has already been stretched to breaking point.

The Weight of Treachery

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

Leading up to the signing of the COT Cases arbitration, on 21 April 1994, AUSTEL wrote to Telstra on 10 February 1994 stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

This internal, dated 25 February 1994, is a Government Memo confirming that the then-Minister for Communications and the Arts had written to advise that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (AFP Evidence File No 4)

Hugh Grant - English actor

On 24 January 2026, the Australian Sun Herald ran a story under the headline: “Hurley weeps in court over devil of a ‘privacy invasion’.”

In London, Elizabeth Hurley broke down as she told the High Court that deeply personal matters she had fought to keep private were now exposed to the world. Her ordeal echoed the experiences of many others, including Prince Harry, Sir Elton John, and David Furnish — all alleging they were victims of unlawful information‑gathering practices. The case referenced intercepted landline calls, covert monitoring, and confessions of systematic intrusion.

For me, the parallels were chilling.

On 21 March 1995, after the government regulator acknowledged that the Australian Federal Police possessed evidence that my own landline service had been secretly monitored without my knowledge or consent, I was asked to present this information to several Senators during the review of the Interception Amendment Act 1991. I did so — the same evidence I had already provided to Detective Superintendent Jeff Penrose of the AFP, who was present at that Senate hearing.

And yet, from that day forward, no one from the government or the AFP has ever raised the matter again. Silence — absolute and deliberate.

As you read through this COT story, you will see how these unresolved privacy violations, left to fester for decades, have taken a devastating toll. They have shortened lives, broken families, and inflicted wounds that never healed. The cost of this silence has been immeasurable.

Living with the following threats has been immeasurable.

In a particularly treacherous move, AUSTEL tampered with its official findings in the AUSTEL COT Cases Report. They deceitfully stated that there were only 50 or so COT Cases with ongoing problems, feeding this false information to the COT arbitrator and the media in April 1994. This was done despite AUSTEL's prior correspondence with Telstra, which acknowledged the government's drastic reduction of an alarming 120,000 COT-type faults to a mere 50 or more (see Chapter 1 - Can We Fix The CAN → (See Open Letter File No/11).

Such a significant distortion of facts should have been exposed in the prospectus, yet it remained buried.

I must take the reader fourteen years forward to the following letter, dated 30 July 2009. According to this letter dated 30 July 2009, from Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson) and ex-client of the arbitrator Dr Hughes (see Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest) wrote to Paul Crowley, CEO Institute of Arbitrators Mediators Australia (IAMA), attaching a statutory declaration (see" Burying The Evidence File 13-H and a copy of a previous letter dated 4 August 1998 from Mr Schorer to me, detailing a phone conversation Mr Schorer had with the arbitrator (during the arbitrations in 1994) regarding lost Telstra COT related faxes. During that conversation, the arbitrator explained, in some detail, that:

"Hunt & Hunt (The company's) Australian Head Office was located in Sydney, and (the company) is a member of an international association of law firms. Due to overseas time zone differences, at close of business, Melbourne's incoming facsimiles are night switched to automatically divert to Hunt & Hunt Sydney office where someone is always on duty. There are occasions on the opening of the Melbourne office, the person responsible for cancelling the night switching of incoming faxes from the Melbourne office to the Sydney Office, has failed to cancel the automatic diversion of incoming facsimiles." Burying The Evidence File 13-H.

Dr Hughes’s failure to disclose the faxing issues to the Australian Federal Police during my arbitration is deeply concerning. The AFP was investigating the interception of my faxes to the arbitrator's office. Yet, this crucial matter was a significant aspect of my claim that Dr. Hughes chose not to address in his award or mention in any of his findings. The loss of essential arbitration documents throughout the COT Cases is a serious indictment of the process.

It is now 2026, and the Australian Federal Police AFP has still not disclosed to me why Telstra senior management has not been brought to account for authorising this intrusion into my business and private life, regardless of Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stating:

"No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks."

A circle of power evaluating itself.A serpent devouring its own tail.A system that had forgotten the meaning of accountability.

A system that protects itself.A system that feeds on silence.A system that leaves citizens wandering through a political nightmare with no guide but their own resolve.In my experience, this was not governance.It was a gothic theatre of power—shadowed, conspiratorial, and merciless.

This DEAL did not address the fact that Freehill Hollingdale & Page was used in the COT arbitrations.

This is concerning because Denise McBurnie from Freehill's was my telephone fault manager, and I had been compelled to register my phone complaints in writing for Telstra to take them seriously and attempt to resolve them. Now, this fault information was being withheld by Freehill's, falsely cited under the claim of Legal Professional Privilege, even though it related to my own registered fault reports. associated with my own registered fault reporting.

I implore anyone delving into this early part of my COT story to thoroughly examine pages 82 to 88, Introduction File No/9 of the Senate Hansard. As shown above, these pages lay bare the insidious monitoring issues highlighted by Senators Calvert and Schacht, as well as the duplicitous actions of John Pinnock, the then Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO). In a despicable manoeuvre, Pinnock deceived Laure James, President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, regarding my arbitration issues during an official investigation into my complaints against Dr Hughes, the arbitrator in my case.

These treacherous lies, had they not been uttered, could have exposed the corrupt and unethical practices that tainted the COT arbitrations, which were conducted under arbitration rules (The Arbitration Agreement) tailor-made by Freehill Hollingdale & Page, instead of the independent arbitration agreement that several Senators, the Parliament House Press, and the COT Cases lawyers had been led to believe was the genuine arbitration agreement drafted independent of Telstra so that the base content of the agreement was free of bias before being scutinised by all parties awaiting our signatures.

On January 27, 1999, after carefully reviewing my detailed report, which I had submitted as a manuscript to the esteemed Major Fraud Group of Victoria Police, Senator Kim Carr took the time to articulate his thoughts in a written response. His words reflected deeply on the findings I presented, highlighting the following:

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

The significance of incorporating the Major Fraud Group into the introduction of my COT story cannot be overstated. This strategic choice is not merely aimed at capturing attention; it establishes a robust framework that enriches the narrative that follows. By opening my account with the Major Fraud Group of Victoria Police, I instantly convey the gravity and credibility of my case, inviting readers to engage with an investigation marked by meticulous scrutiny and professional rigour.

The engagement of the Major Fraud Group signals that my concerns were taken with the utmost seriousness, framing the investigation as a critical matter deserving of high-level attention. When two distinguished barristers—Mr. Neil Jepson, representing the formidable Major Fraud Group, and Sue Owens, representing the four COT cases—approached me with alarming allegations of serious fraud perpetrated by Telstra, it marked a defining moment in my journey. Their involvement indicates that my claims against Telstra, as well as the integrity of the arbitration process, carry considerable legitimacy, compelling legal professionals and specialised investigators to probe deeply into the gravity of my allegations.

Collaborating with such authoritative bodies serves as a profound testament to my credibility. Over the course of an exhaustive 13 months during my secondment, I engaged in extensive dialogue and cooperation with both barristers and five dedicated detectives from the Major Fraud Group. This level of rigorous scrutiny and support from government entities emerges only from a thorough vetting of my background and character, confirming me as a reliable witness in a high-stakes inquiry. By presenting this vital information at the outset of my absentjustice.com website and in my publication titled "The Arbitraitor," I ensure that readers comprehend that my role in the investigation was not self-appointed; it was recognised and validated by official channels devoted to uncovering the truth.

Beginning my narrative through the lens of a police investigation establishes a factual, grounded tone that resonates deeply with the story's essence. It communicates to readers that the unfolding events are not merely personal grievances; they are underscored by documented evidence, professional diligence, and formal inquiries, thus moving beyond subjective interpretation into the realm of established fact.

By highlighting the Major Fraud Group's investigation into Telstra’s conduct, I transcend a simple recounting of disputes into an impactful public-interest story. The issues raised during the COT arbitrations were far from trivial; they warranted the focused attention of specialists trained to uncover fraud and misconduct. This transition elevates my narrative from a private struggle into a matter that embodies the urgent need for public accountability and transparency.

Additionally, my extensive 13-month collaboration with the investigators provides me with a unique perspective that adds depth to my story. By introducing this significant experience early in the narrative, I prepare readers to appreciate that my insights are not rooted in speculation but in firsthand involvement in an intricate, high-stakes inquiry. This detailed foundation enhances the authority and balance of everything that follows on absentjustice.com, positioning my story as one of informed advocacy and a sincere exploration of justice, infused with the weight of real-world implications and the hope for transformative change.

If you've decided to explore this website to gain insights into the concept of Absent Justice in Australia, I invite you to click on the link titled "The eighth remedy pursued" This will allow you to delve deeper into the intricacies of my Casualties story, revealing layers of truth that may surprise many.

Major Fraud Group - Victoria Police

While the issue concerning the 24,000 FOI documents related to the arbitration has been discussed above, I want to emphasize the significant disadvantage I faced due to their late delivery, which prevented me from including them in my original letter of claim. As a result, I was unable to demonstrate to the arbitrator that my phone and fax issues continued to affect my business. The late-arriving documents, some sourced from Telstra's telephone exchanges that served my business, revealed that AUSTEL was still seeking answers from Telstra even after the arbitrator had concluded that my phone problems had been resolved.

All the main statements presented on this website, including those that are merely comments, are supported by at least one, and often three to five, pieces of evidence. However, I want to highlight a specific statement regarding what Neil Jepson, Barrister for the Major Fraud Group, said to me in the Chambers of the Supreme Court of Victoria. We were both called to provide evidence on behalf of Barrister Sue Owens, but I cannot support this statement with documents. Since my next statement relies solely on my word regarding what Mr Jepson said, I ask that everyone who has read the comments on absentjustice.com keep this in mind when considering his remarks; he has since passed away.

Mr Jepson’s remarks expose a deeply sinister reality: the evidence presented to the Major Fraud Group regarding the duplicitous statements made by Dr Gordon Hughes to Laurie James, the esteemed President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, is nothing short of shocking. Dr Hughes claimed that he and his technical advisors had meticulously reviewed all 24,000 documents; however, these documents were never submitted for appropriate arbitration assessment.

The Major Fraud Group, along with Tony Morgon, the Chief Loss Assessor from GAB Robins—international assessors appointed by the Commonwealth Ombudsman—unearthed a disturbing truth: I did not submit these 24,000 FOI-released documents for arbitration due to Telstra's deliberate delays, which left me with inadequate time for a thorough review. In a further act of malice, Dr Hughes categorically denied me the opportunity to present a mini-report that I had painstakingly compiled from these documents.

Dr Hughes's actions amounted to a calculated misrepresentation of Laurie James during an official investigation, and his refusal to confront the lies—whether he or his advisors were responsible—constitutes a grave betrayal of trust that weighs heavily on all involved.

Mr Jepson also pointed out that the Major Fraud Group continues to investigate the dubious claims made by Arbitration Project Manager John Rundell regarding the Brighton Criminal Investigation Branch. Rundell pretended that they were preparing to interrogate me about alleged criminal damage to his property; however, no such inquiry ever materialised. If there had been any legitimate suspicion against me, the Major Fraud Group and Victoria Police would not have sought my expertise on the fraud allegations involving Sue Owens’ clients. This entire scenario reeks of complicity and corruption at multiple levels.

It is both tragic and infuriating that Mr Pinnock, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, continued to operate with alarming impunity for several years after this disclosure. He made outrageous accusations against Laurie James, alleging that I had written to him claiming I had called Dr Hughes’ wife at 2:00 AM. Yet no such letter exists in any official records. This assertion is not only patently false, but our thorough investigation has also confirmed that I neither penned such a letter nor made that fateful call.

It is utterly heartbreaking that I must navigate through life bearing the scars inflicted by these insidious lies.

The following five chapters show how arbitration officials misrepresented the truth.

It is essential to inform the reader that if they click on Chapter 1 - The Collusion Continues, and read that chapter—attached to the Open Letter dated 25/09/2025—followed by Chapter 2 - Inaccurate and Incomplete, Chapter 3 - The Sixth Damning Letter, Chapter 4 - The Seventh Damning Letter, and Chapter 5 - The Eighth Damning Letter, they will be left with no doubt whatsoever that my claims surrounding mR Neil Jepson are true and correct

After reading the five chapters above, it becomes undeniably clear that the three named arbitration officials—Dr. Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator handling my case; John Rundell, the Arbitration Project Manager; and John Pinnock, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman and second appointed administrator, failed to accurately represent the facts during my arbitration and throughout the critical period leading up to 1996.

Arbitration in Australia—A System Compromised by Deception and Betrayal

For decades, I have fought to expose the corruption embedded within the Australian arbitration system, particularly as it relates to the Casualties of Telstra (COT) cases. What follows is not speculation. It is a documented account of lies, fabrications, and institutional complicity that thwarted legitimate appeals and silenced voices seeking redress.

Fabricated Allegations to Discredit and Silence

In an attempt to undermine my arbitration appeal, a false allegation was circulated claiming that I verbally harassed the wife of Dr. Gordon Hughes AO, the arbitrator overseeing my case. This defamatory claim originated from John Pinnock, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, and was sent to Laurie James, the President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia. I categorically deny this allegation. It was a deliberate effort to damage my reputation and divert attention from the serious flaws in the arbitration process.

Dr Hughes, aware of the falsehood, chose silence over integrity, allowing this lie to undermine the legitimacy of the proceedings. The emotional toll of being wrongfully accused—and of being betrayed by those meant to uphold justice—has been profound. Nonetheless, my commitment to uncovering the truth remains unwavering.

During my pending appeal, my attorneys at Law Partners in Melbourne advised me to contact John Pinnock regarding documents related to my arbitration that could help challenge the unjust award issued by Dr Hughes. Unbeknownst to me, this request would lead to further deceit. In his letter dated January 10, 1996, Pinnock dismissed my request for these records, stating he would not provide any documents held by his office. This was just the beginning of a lengthy ordeal filled with treachery.

Dr Hughes was central to this scheme. He refused to release my pre-arbitration files—evidence that would reveal his role as an "assessor" in four COT cases, contrary to the impartial arbitrator he claimed to be. His actions manipulated the arbitration agreement and undermined the genuine contract, further entrenching corruption. By October 1995, five months after my arbitration had concluded, I had to involve the Commonwealth Ombudsman. Working with the Ombudsman's Director of Investigations, John Wynack, we challenged Telstra’s misleading claims regarding the destruction of key files.

In 2008, driven by outrage, I launched a two-stage appeal through the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, only to uncover further institutional collusion by the government itself. Even now, in 2025, I remain blocked from accessing the one document that could expose the corruption at the heart of this process. This betrayal runs deep within a system that rewards secrecy and punishes whistleblowers. Throughout my 30 years as a seafarer and in various roles on the Australian waterfront, I have encountered many resilient individuals. Yet, none have resorted to hiding behind others for protection as Dr Gordon Hughes continues to do.

The Disclosure That Never Came

On January 23, 1996, Dr Hughes wrote to John Pinnock, the then Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), regarding my situation, expressing concerns about the potential costs and implications of responding to the allegations raised against him. His letter hinted at the complex and fraught nature of the proceedings unfolding.

Please examine the following two witness statements. The Major Fraud Group archive documents will be confirmed as faxes sent from my office, and Mr Jepson did not arrive, despite my Telstra fax account showing that the faxes were indeed sent.

This situation troubled Mr Jepson and Detective Sergeant Rod Kuris, who was assisting us in piecing together documents related to the fraud. It is evident from Des Direen's testimony, the former Principal Telstra Security Officer, that Mr Rod Kuris was visibly shaken when Des Direen informed us that we were under electronic surveillance, as indicated in the following witness statement.

"I can recall that during the period 2000/2001, I had arranged to meet Detective Sergeant Rod KURIS from the Victoria Police Major Fraud Squad at the foyer of Casselden Place, 2 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. At the time, I was assisting Rod with the investigation into alleged illegal activities against the COT Cases.

Rod then stated that he wanted me to follow him to the left side of the foyer. When we did this he then directed my attention to a male person seated on a sofa opposite our seat. He then told me that the person had been following him around the city all morning. At this stage Rod was becoming visibly upset and I had to calm him down. Rod kept on saying that he couldn't believe in what was happening to him. I had to again calm him down".

Points 21 and 22 in Mr Direen’s statement also record how, while he was a Telstra employee, he had cause to investigate “… suspected illegal interference to telephone lines at the Portland exchange,” but when he “… made inquiries by telephone back to Melbourne (he) was told not to get involved and that another area of Telstra was handling it” and that “... the Cape Bridgewater complainant was a part of the COT cases” (my Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp) business.

Major Fraud Group Evidence 1 - Tampering with Evidence

This evidence was prepared at the request of Mr Neil Jepson and was highly praised for its professional quality, as noted by Barrister Sue Owens in Transcript (1). The reports in question are Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2 and "Tampering with Evidence." Mr Jepson believed that combining these two reports could help strengthen my arbitration appeal. This is also supported by statements made in the (see Major Fraud Group Transcript (1).

Concealing A Crime

This tampering with evidence, after a claimant has provided it to an arbitration process, including (again, in my case) changing that evidence into a different format, must be one of the worst crimes a defendant (in this case, the Telstra corporation) could have committed against an Australian citizen. So why, when evidence of this tampering was provided – twenty years ago to the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (John Pinnock), the Chair of the TIO’s Counsel (The Hon Tony Staley), the Chair of the Telstra Board (David Hoare), and Telstra’s then-CEO (Ziggy Switkowski AO), was that evidence not investigated immediately?

It was Telstra’s own internal investigations that revealed this unlawful conduct during my arbitration. However, this did not prevent Ziggy Switkowski from accepting an Order of Australia award several years ago, along with Warwick Smith, the administrator of my arbitration, and Dr Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator in my case. All three have been aware of this wrongdoing for thirty years.

Exhibit 10-C → File No/13 in the Scandrett & Associates report Pty Ltd fax interception report (refer to (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) confirms my letter of 2 November 1998 to the Hon Peter Costello Australia's then Federal Treasure was intercepted scanned before being redirected to his office. These intercepted documents to government officials were not isolated events, which, in my case, continued throughout my arbitration, which began on 21 April 1994 and concluded on 11 May 1995. Exhibit 10-C File No/13 shows this fax hacking continued until at least 2 November 1998, more than three years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

Whoever had access to Telstra’s network, and therefore the TIO’s office service lines, knew – during the designated appeal time of my arbitration – that my arbitration was conducted using a set of rules (arbitration agreement) that the arbitrator declared not credible. There are three fax identification lines across the top of the second page of this 12 May 1995 letter:

- The third line down from the top of the page (i.e. the bottom line) shows that the document was first faxed from the arbitrator’s office, on 12-5-95, at 2:41 pm to the Melbourne office of the TIO – 61 3 277 8797;

- The middle line indicates that it was faxed on the same day, one hour later, at 15:40, from the TIO’s fax number, followed by the words “TIO LTD”.

- The top line, however, begins with the words “Fax from” followed by the correct fax number for the TIO’s office (visible

Consider the order of the time stamps. The top line is the second sending of the document at 14:50, nine minutes after the fax from the arbitrator’s office; therefore, between the TIO’s office receiving the first fax, which was sent at 2.41 pm (14:41), and sending it on at 15:40, to his home, the fax was also re-sent at 14:50. In other words, the document sent nine minutes after the letter reached the TIO office was intercepted.

PLEASE NOTE:

Although the TIO's Senate Hansard admission on 26 September 1997 was addressed earlier, it is still important to connect its content to the narrative that follows. This is particularly relevant in light of John Pinnock (TIO) alerting the government to this significant denial of justice.

On 26 September 1997, Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman John Pinnock formally addressed a Senate estimates committee refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D). He noted:

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

There have been no amendments to the agreements signed by the first four members of COT that would permit the arbitrator to conduct the arbitration beyond the established procedures, yet it seems an unsettling shift is underway. The agreements remain silent on the crucial detail that the arbitrator would forfeit control over the process once we each committed to our individual agreements. In this alarming context, how can the arbitrator and the TIO continue to lean on the confidentiality clause in our arbitration agreement?

This clause fails to specify that the arbitrator would have no authority, especially when the arbitration is being orchestrated entirely outside the frameworks we initially established. This situation not only undermined the integrity of the arbitration process but also raised serious concerns that corruption and treachery may already have begun to seep into the very foundation of our proceedings before they even commenced, as the following example shows

In late 1999, Frank Blount—then recently departed CEO of Telstra—co‑authored a book titled 'Managing in Australia'. In it, he openly acknowledged the very software billing problems that Telstra executives had denied under oath during my arbitration. On pages 132 and 133, the co‑author describes Telstra’s 1800‑service faults in blunt terms:

- “Blount was shocked, but his anxiety level continued to rise when he discovered this wasn’t an isolated problem.

- The picture that emerged made it crystal clear that performance was sub-standard.” (See Exhibit 122-i → AS-CAV Exhibit 92 to 127)

This admission stands in stark contrast to the sworn statements made by nine Telstra executives during my arbitration, all of whom insisted that my business was not suffering from ongoing billing problems—despite Telstra’s board knowing otherwise.

Lying during litigation is not a trivial matter. It strikes at the heart of justice. In both the British Post Office case (a government‑owned institution) and the Telstra case (also government‑owned at the time), officials swore under oath that no software billing issues existed. These were not innocent mistakes. They were orchestrated falsehoods, engineered by bureaucrats whose duty was to protect citizens, not destroy them.

It is essential to expose the treachery of both the British and Australian governments—and the bureaucracies that enabled these injustices. Their complacency and complicity reveal the profound challenges faced by ordinary people when institutions designed to uphold justice instead choose to bury the truth. The COT Case Government-Endorsed Arbitrations were nothing more than manipulated Kangaroo Court procedures.

One of the most scandalous episodes in my own arbitration occurred on 16 October 1995, when government‑appointed bureaucrats allowed Telstra and the arbitrator to covertly address the systemic billing faults that had crippled my business. This took place five months after Dr Hughes issued my award on 11 May 1995—an award that offered no remedy for the very faults that had destroyed my livelihood. Dr Hughes had a clear duty to ensure that Telstra resolved these critical issues before closing my case. Instead, the process was manipulated behind closed doors, revealing an arbitration system stripped of integrity and justice (see Absent Justice Part 2 - Chapter 14 - Was it Legal or Illegal?).

By permitting Telstra to address my ongoing billing faults in camera, Dr Hughes and the government officials overseeing the process violated my legal rights under the arbitration agreement. They denied me the opportunity to challenge Telstra’s claims—a fundamental right in arbitration processes worldwide. Each party must be allowed to respond to the other’s assertions. That principle was abandoned.

The British Post Office scandal and the Telstra–Ericsson billing scandal are not isolated events. They are twin examples of what happens when bureaucracies close ranks, conceal the truth, and sacrifice citizens to protect themselves. Both nations now face the consequences of that betrayal.

• Telstra’s legal team had devised strategies to conceal technical evidence from COT claimants under the guise of legal privilege—even when the data wasn’t privileged.• The arbitrator failed to make findings on persistent faults, despite overwhelming evidence, possibly to avoid undermining Telstra’s market value during privatisation.• The Australian Government was simultaneously promoting Telstra’s sale, creating a conflict of interest between justice for claimants and financial gain from the sale.

• Horizon falsely accused thousands of contractors of fraud, based on faulty data.• Telstra’s billing systems were known to mischarge customers, yet these faults were not addressed in arbitration.• If Telstra’s revenue was artificially inflated, its privatisation may have misled investors and regulators.

• Regulatory capture: Government and corporate interests aligned to suppress damaging truths.• Investor deception: If faults were concealed, Telstra’s sale may have violated disclosure norms.• Historical injustice: The COT Cases were sacrificed to protect a corporate transaction.

• Side-by-side comparison of both scandals• Quotes from Alan Bates and Frank Blount• Analysis of regulatory failure and public impact• Call for a similar public inquiry and redress in Australia