Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers.

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government-owned Australia's telephone network and the communications carrier, Telecom (today privatised and called Telstra). Telecom held a monopoly on communications and allowed the network to deteriorate into disrepair. Instead of our very deficient telephone services being fixed as part of our government-endorsed arbitration process, which became an uneven battle we could never win, they were not fixed as part of the process, despite the hundreds of thousands of dollars it cost the claimants to mount their claims against Telstra. Crimes were committed against us, and our integrity was attacked and undermined. Our livelihoods were ruined, we lost millions of dollars, and our mental health declined, yet those who perpetrated the crimes are still in positions of power today. Our story is still actively being covered up.

“Our local technicians believe that Mr Smith is correct in raising complaints about incoming callers to his number receiving a Recorded Voice Announcement saying that the number is disconnected.

“They believe that it is a problem that is occurring in increasing numbers as more and more customers are connected to AXE.” (See False Witness Statement File No 3-A)

To further support my claims that Telstra already knew how severe the Ericsson Portland AXE telephone faults were, can best be viewed by reading Folios C04006, C04007 and C04008, headed TELECOM SECRET (see Front Page Part Two 2-B), which state:

“Legal position – Mr Smith’s service problems were network related and spanned a period of 3-4 years. Hence Telecom’s position of legal liability was covered by a number of different acts and regulations. … In my opinion Alan Smith’s case was not a good one to test Section 8 for any previous immunities – given his evidence and claims. I do not believe it would be in Telecom’s interest to have this case go to court.

“Overall, Mr Smith’s telephone service had suffered from a poor grade of network performance over a period of several years; with some difficulty to detect exchange problems in the last 8 months.”

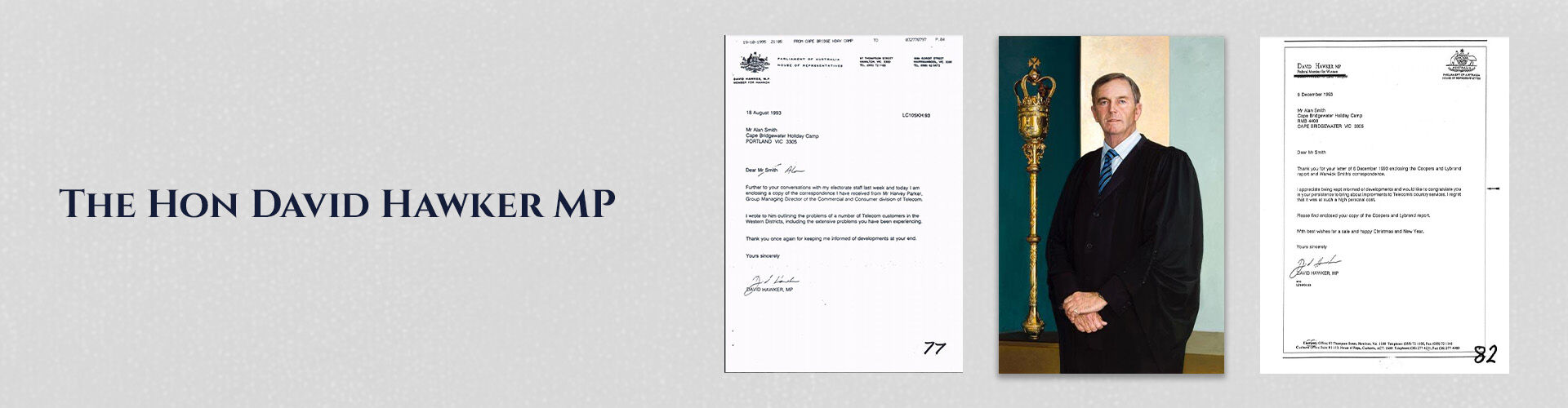

The correspondence I received dated 9 December 1993 was not only affirming but also deeply compassionate, reflecting his concern.

A similar compassionate letter, from the Hon. David Beddall MP, Minister for Communications in the Labor government, to Senator Michael Baume, a member of the opposition. In his letter, Minister Beddall addressed Senator Baume, who was profoundly touched by the details of my situation. During a session in Parliament House, Senator Baume was visibly moved upon hearing about the significant hardships three other Casualties of Telstra and I had endured during six long years without a reliable phone service.

In his heartfelt letter, Minister Beddall expressed genuine empathy for those affected by the alleged shortcomings of Telecom. He stated to Senator Baume that:

“The Government is most concerned about allegations that Telecom has not been maintaining telecommunications service quality at appropriate levels.”

He went on to acknowledge the distress that many, including myself, had experienced, noting,

“I accept that in a number of cases, including Mr Smith’s, there has been great personal and financial distress.”

This acknowledgement was more than a formal remark; it was a poignant recognition of the struggles faced by individuals caught in this situation.

Although we initially faced harsh backlash, our stand against Telstra soon proved to be entirely justified. We uncovered that over 120,000 other customers across Australia were suffering from the same issues, all due to Telstra's brazen denial of any faults with the Ericsson AXE telephone exchange equipment. In response to our revelations, we, the COT Cases, were labelled by Telstra as treacherous whistleblowers, targeted by a ruthless campaign to discredit us. Those powerful executives within Telstra wielded their influence like weapons, cunningly digging deep to obliterate every claim we made, all to protect their corrupt interests. (Arbitrator File No/82)

The government that once stood with us closed their eyes to what became a vendetta by Telstra, as the following narrative shows.

To ensure that what happened to me — and to thousands of others — would not be erased, forgotten, or repeated.That purpose gave me strength.It gave me direction.It gave me a reason to keep going when everything else had been taken.And that purpose is what carries me into the next chapter.

The Ericsson List: A Shadow Over Australian Justice

I have spent years trying to explain to people how something so brazen, so corrupt, and so deeply sinister could have happened in a country that prides itself on fairness and due process. Yet the truth is as stark as it is undeniable: Telstra’s principal supplier of telephone equipment — equipment riddled with faults in the very exchanges servicing the COT Cases — managed to slip straight into the heart of Australia’s arbitration system. It didn’t happen by accident. It wasn’t a misunderstanding. It was a calculated infiltration.

And while this was unfolding, Ericsson stood towering over the global telecommunications world — a behemoth operating in the shadows, entangled in dealings that would later be exposed in the Ericsson List. That list lays bare a reality most Australians would never believe: Ericsson collaborating with terrorists, financing covert operations, and orchestrating shady deals across continents, all in pursuit of profit. Yet this was the company the Australian Government allowed to step directly into our arbitrations.

None of the COT Cases was granted leave to appeal their arbitration awards—even though it is now clear that the purchase of Lane by Ericsson must have been in motion months before the arbitrations concluded. It is crucial to highlight the bribery and corruption issues raised by the US Department of Justice against Ericsson of Sweden, as reported in the Australian media on 19 December 2019.

One of Telstra's key partners in the building out of their 5G network in Australia is set to fork out over $1.4 billion after the US Department of Justice accused them of bribery and corruption on a massive scale and over a long period of time.

Sweden's telecoms giant Ericsson has agreed to pay more than $1.4 billion following an extensive investigation which saw the Telstra-linked Company 'admitting to a years-long campaign of corruption in five countries to solidify its grip on telecommunications business. (https://www.channelnews.com.au/key-telstra-5g-partner-admits-to-bribery-corruption/)

We were forced to accept their influence. Forced to accept their access. Forced to accept their power.

Everything changed the moment Ericsson purchased Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd — right in the middle of the arbitration process. Lane wasn’t just any consultancy. Lane was the technical unit appointed to investigate the very faults we had raised against Ericsson’s AXE telephone exchange equipment. They held the evidence. They held the data. They held the truth.

Ericsson held all the cards—every last one of them.

I have separated this part of the Ericsson story and intertwined it with the FOI Folio document K01006 because something deeply disturbing occurred in my Ericsson AXE arbitration file—the very documents I provided to David Reid of Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd.

A 43-page chronology of events, using similar unexplained documents, tracked the monitoring of my business, including Folio document K01006, as described below. This 43-page Ericsson AXE report showed that I had lost twenty-seven incoming calls on three specific dates when Telstra indicated they would document all faults—September 5, 1994, to August 8, 1994. However, my chronology for those dates is missing from my claim documents, along with over 200 other unassessed Ericsson AXE claim documents that formed this 43-page arbitration submission.

The report was never returned to me after my arbitration, despite the arbitration rules requiring its return.

As shown in the technical report dated April 30, 1995, both David Reid (Lane) and Paul Howell (DMR Canada) stated that they were not provided with a comprehensive log of my fault complaints, as indicated in Chapter 1 - The Collusion Continues.

The Telstra internal email in question, dated Thursday, April 7, 1994, at 2:95 PM and signed by Bruce Penlebury—FOI Folio K01006—was sent to someone named David. The email states:

“David, Mr Alan Smith is absent from his premises from 5/9/94 to 8/8/94. I intend on this occasion to document his absence and file all data I can collect for the period. That way, we should be prepared for anything that follows.”

Prepared for anything that follows. That line alone reeks of foreknowledge—of a plan already in motion.

Had Ericsson begun their infiltration of the COT arbitrations long before it became common knowledge that Lane had compromised their integrity for thirty pieces of silver?

From that moment, every piece of technical evidence Lane had compiled — every fault record, every analysis, every finding — became Ericsson’s property. The material that should have protected us was now in the hands of the corporation it incriminated. It vanished from the public arena in one silent, devastating sweep.

I was advised at the time by Mr Jepson to gather everything I could — every document, every letter, every technical report — and assemble a mini‑dossier identifying the three individuals whose conduct had shaped the outcome of my arbitration: the arbitrator, the administrator, and the arbitration project manager. He told me to show, clearly and without hesitation, how their combined actions had denied me justice. I did exactly that.

But even that report could not compete with what was happening behind closed doors.

What unfolded was nothing short of a treacherous conspiracy — a scheme so meticulously orchestrated that it eroded the very foundations of democratic accountability. Lane, the consultancy entrusted to provide impartial technical advice, was quietly absorbed by the very corporation it was investigating. The Australian Government, fully aware of the conflict, allowed the transaction to proceed without objection. The arbitration process they had endorsed lost its legitimacy the moment Ericsson took control of its own investigator.

And the government said nothing.

The theft of evidence was complete. The silence was deafening.

The situation grew darker still when Ericsson later admitted to the US Department of Justice that it had been involved in dealings with terrorists. That admission alone should have triggered an immediate reevaluation of every COT Case involving Ericsson equipment — especially the AXE system faults that had plagued our businesses for years. Lane had been the investigating officer for those claims. Lane had been purchased by Ericsson while the COT arbitrations were still in progress. Lane’s findings were now tainted beyond repair.

Yet the Australian Government did not lift a finger.

No review. No reassessment. No accountability.

Instead, the Howard Government allowed only five of the twenty‑one COT Cases to be resolved during the Senate Committee investigations — the five “litmus‑test” cases. The remaining sixteen were left out in the cold. Many of those sixteen had raised serious claims about the known locking‑up faults in Ericsson’s AXE equipment. Had those cases been properly examined, the truth about the AXE system would have been impossible to hide.

But there was something else at stake: the Telstra sale prospectus.

If the full extent of the AXE faults had been exposed, the value of Telstra — and the government’s plans to privatise it — would have been severely compromised. So the remaining COT Cases were quietly pushed aside. Their evidence was ignored. Their claims were buried.

And the question that has haunted me ever since is this:

Was Ericsson allowed to purchase Lane Telecommunications to help bury the truth about its failing infrastructure inside Telstra’s exchanges — just in time for the Telstra sale?

The pattern is too clear to ignore. The timing is too convenient. The silence was too deliberate.

This is not just a story of corporate misconduct. It is a story of a government that looked the other way while a multinational corporation seized control of an Australian arbitration process. It is a story of stolen evidence, denied justice, and undermined democracy.

And it is a story I can prove. → Chapter 5 - US Department of Justice vs Ericsson of Sweden,

Major Fraud Group - Victoria Police investigation

In late 1999, after being seconded to assist the Major Fraud Group of Victoria Police, I was informed by Mr Neil Jepson, a barrister for the group and a professional associate and friend of my forensic accountant, Derek Ryan from DMR Corporate Melbourne, about a significant issue. Mr Jepson revealed that many members of the establishment, including the three arbitration administrators mentioned below, were involved in covering up the systemic billing problems I had uncovered. These issues affected thousands of Australian citizens and seemed to involve a coordinated effort to conceal my evidence.

Mr Jepson advised me to link the three main players in my arbitration, whom I believed had acted without bias, and to gather as much information as possible regarding their conduct during and after the arbitration. Once I collected that information, the next step would be to consolidate the material and link it to the three individuals I believed had acted unlawfully. I needed to build a profile and ultimately expose these three individuals for having collectively disadvantaged me. With some luck, this process might reveal critical evidence that would leave these players vulnerable and exposed.

Two other members of the Major Fraud Group discussed this matter with me after contacting Carlton & United Breweries in Melbourne. Their response revealed a troubling truth: both Dr Gordon Hughes, the previous arbitrator in my case, and John Pinnock, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman who oversaw my arbitration, failed to report the critical information I provided. This information was eventually forwarded to Telstra's then-CEO, Ziggy Switowski, and to David Hoare, the Chairman of the Telstra Board, which unequivocally validated my claims (refer to Exhibits Open Letter File Nos/36, 37 and File No/38, and Tampering with Evidence).

In his statement on 26 September 1997, Mr Pinnock disingenuously noted:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures, the claimants were clearly informed that documents would be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, as it was conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

Remarkably, Pinnock made no acknowledgement to the Senate of his previous misleading claims to Laurie James about my case. He failed to address how he used Dr Hughes' wife as a convenient shield for Hughes himself. This episode is just one of many distressing experiences the COT Cases have endured, revealing a pattern of corruption and betrayal among those in positions of power.

The Establishment

When I talk about the Establishment, I’m not using the word lightly. I use it because that is exactly who stood behind Telstra during the years of my arbitration. It wasn’t just a corporation defending itself. It was the lawyers who became arbitrators, the government departments who owned Telstra, and the powerful interests who were always looked after first. They protected one another with a loyalty that ordinary Australians could never hope to receive.

I saw it up close in the 1990s. While small business operators like me were forced to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in arbitration fees just to get the telecommunications services we were already entitled to, the Establishment opened the vault for the powerful. When Rupert Murdoch and Fox demanded compensation because Telstra couldn’t meet their telecommunications requirements, the government didn’t hesitate. They handed over a deal worth up to $400 million. No arbitration. No delays. No hoops to jump through. Just a quiet agreement to keep the powerful satisfied.

Meanwhile, the rest of us were left to fight for every scrap of justice we could get.

And that’s when I realised something that has stayed with me ever since:

In Australia, the Establishment always looks after its own.

Call for Justice

10. Telstra's CEO and Board have known about this scam since 1992. They have had the time and the opportunity to change the policy and reduce the cost of labour so that cable roll-out commitments could be met and Telstra would be in good shape for the imminent share issue. Instead, they have done nothing but deceive their Minister, their appointed auditors and the owners of their stockÐ the Australian taxpayers. The result of their refusal to address the TA issue is that high labour costs were maintained and Telstra failed to meet its cable roll-out commitment to Foxtel. This will cost Telstra directly at least $400 million in compensation to News Corp and/or Foxtel and further major losses will be incurred when Telstra's stock is issued at a significantly lower price than would have been the case if Telstra had acted responsibly.

11. Telstra not only failed to act responsibly, it failed in its duty of care to its shareholders. So the real losers are the taxpayers and to an extent, the thousands of employees who will be sacked when Telstra reaches its roll-out targetÐcable past 4 million households, or 2.5 million households if it is assumed that Telstra's CEO accepts directives from the Minster.

A Pattern Older Than My Case

What happened to the COT Cases wasn’t new. It was part of a long, ugly tradition in this country — a tradition where ordinary people are punished for standing up, while the powerful are shielded from scrutiny.

I grew up hearing stories of the shearing strikes, where men who simply wanted fair wages were dragged before Magistrates’ Courts and branded as troublemakers. The Establishment used words like “attacking scab labour” to justify punishing them. Some of those men were sentenced to three months’ hard labour. Others received two years for “conspiracy”. Their crime was refusing to work for food alone while their families starved.

The Establishment always had a way of turning the victim into the villain.

And decades later, when I challenged Telstra, I found myself in the same position.

Threatened for Telling the Truth

Exposing the truth meant I faced a possible jail term.

It may be unsettling to confront, but in August 2001 and again in December 2004, the Australian Government issued chilling written threats (see Senate Evidence File No 12) warning me of potential contempt charges if I even dared to reveal the sinister contents of the in-camera Hansard records from July 6 and 9, 1998.

When I uncovered evidence of Telstra’s misconduct — evidence the Establishment desperately wanted hidden — I was warned that if I made certain Senate Hansard recordings public, I could be charged with Contempt of the Senate (Refer to Telstra-Corruption-Freehill-Hollingdale & Page)

Imagine that.

A small business operator is threatened with prosecution for exposing the truth.

Those two Hansard records, dated 6 and 9 July 1998, remain unreleased to this day. Not because they lack importance, but because the threat was real. The Establishment had the power to make good on it.

I will be 82 years old in May 2026. I live with a pacemaker after suffering two heart attacks. If I end up going to jail, will my pacemaker be taken into consideration? I witnessed how the government responded when Telstra threatened me during my arbitration, stating that if I continued to assist the Australian Federal Police with their corruption investigations into Telstra, my arbitration would be at risk. I refused to be intimidated and continued to support Superintendent Jeff Penrose of the AFP despite the very real threats.

The following 93 questions were posed to me by the Australian Federal Police (AFP), along with my responses, as detailed in Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1. My answers reveal a disturbing truth: Telstra issued direct threats against me for daring to assist the AFP in its investigations into the interception of my phone conversations and the illicit hacking of documents related to my arbitration.

Telstra compromised my arbitration by carrying out these threats right in front of the arbitrator, the AFP, and the government. Therefore, I doubt that my pacemaker would provide me any protection if I were to serve jail time for being in contempt of the Senate, especially if I were attacked by an inmate loyal to the Establishment.

Yet when Telstra employees were caught in contempt of the Senate, nothing happened. No charges. No hearings. Not even a raised eyebrow.

That is the difference between being part of the Establishment and standing outside it.

Thirty Years of Protection

For thirty years, the Establishment protected Telstra. They protected the lawyers who ran the arbitrations. They protected the officials who misrepresented justice. They protected the lies, the withheld documents, the fabricated reports, and the people who orchestrated them.

And through all of it, we — the COT Cases — were expected to simply endure it.

But we didn’t just endure it.

We survived it. That is what this story is really about. Not just the phone faults.Not just the documents. Not just the lies. It is about surviving a crooked legal process designed to break us — and refusing to let the Establishment write the ending.

Threats made and carried out.

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no intention of submitting any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call I received from Steve Black, another arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, Black issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions he and Mr Rumble gave, I would jeopardise my access to crucial documents pertaining to ongoing problems I was experiencing with my telephone service.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could affect the arbitrator's decisions in my case.

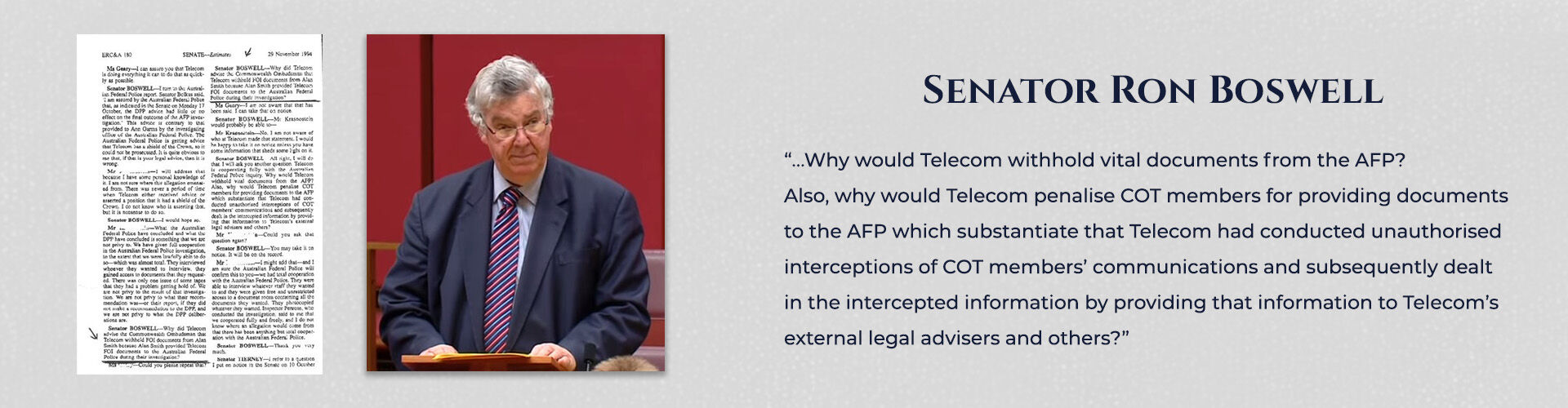

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on 26 September 1994. During this visit, they began asking probing questions about my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating a sense of urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

As a result, I contacted Senator Ron Boswell, who subsequently brought these threats to the Senate's attention. This statement underscored the serious nature of the claims I was dealing with and the potential ramifications of my interactions with Telstra.

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

Thus, the threats became a reality. What still appals me, even now, is not just the brutality of the tactics used against me, but the cold indifference that followed. The withholding of my documents wasn’t a clerical error or an unfortunate oversight — it was a deliberate act, executed with precision, and designed to cripple my case before it ever reached the arbitrator’s desk.

And yet, no one — not a single person in the TIO office, nor anyone within the government — has ever investigated the catastrophic impact this withholding had on my submission. They never asked how many pages were missing, how many arguments were silenced, or how many opportunities for justice were quietly erased before I even had a chance to speak. They simply looked the other way, as if the damage done to an Australian citizen was nothing more than an administrative inconvenience.

What makes this betrayal even more sinister is the context they all conveniently ignored. At the time, Telstra was still a government‑owned entity. The arbitrator was operating under the authority of a government‑endorsed process. And I — the person they allowed to be ambushed and disadvantaged — had been assisting the Australian Federal Police in their investigation into unlawful interception of telephone conversations.

Think about that.

A citizen who stepped forward to help expose illegal conduct was then left defenceless in a civil arbitration, stripped of the very documents that could have proven his case. If ever there was a moment when the arbitrator and the government should have intervened — should have demanded answers, should have protected the integrity of the process — it was then.

But they didn’t.

They stayed silent. They allowed the damage to stand. They allowed Telstra’s advantage to harden into something immovable. And in doing so, they revealed the treacherous truth at the heart of the arbitration: the process was never designed to protect me. It was designed to protect them.

The threats weren’t just words. They were a warning of what was coming — a warning that the system itself was prepared to sacrifice fairness, transparency, and even basic decency to shield Telstra from accountability.

And that is exactly what happened.

Pages 12 and 13 of the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 transcripts provide a comprehensive account that establishes Paul Rumble as a significant figure linked to the threats I have encountered. This conclusion is based on two critical and interrelated factors that merit further elaboration.

Bribery and corruption aren’t abstract concepts to the Casualties of Telstra. They’re not words from a textbook, or warnings whispered in a lecture hall. I’ve seen them up close — not in the open, where sunlight might expose them, but in the dim corridors where decisions are made quietly, signatures are traded like currency, and the truth is treated as something inconvenient, something to be managed.

What struck me first was the silence. Not the peaceful kind — the dangerous kind. The kind that tells you something is happening behind closed doors, and you’re not meant to know about it. The kind that makes you realise you’re standing on the outside of a machine designed to grind you down.

And that machine had operators.

They weren’t the thugs or crooks you’d expect. No — these were polished professionals. Bankers with immaculate suits. Lawyers who smiled as they gutted your rights. Accountants who could make a number disappear as easily as a magician palms a coin. Arbitrators who pretended to be neutral while quietly steering the ship exactly where their handlers wanted it to go.

In the hushed, climate-controlled sanctuaries of the top floor, human devastation is merely white noise. To these Telstra executives, your life wasn't a story; it was a nuisance variable to be amortized. They didn't just ignore the screams from below—they used the acoustics of the building to dampen them.They spoke a dialect of sanitised violence. They didn't "destroy" families; they "optimised the portfolio." They didn't "lie"; they "managed the narrative." Their coldness was a physical weight, a frost that crept across the mahogany table every time an arbitrator traded a victim’s future for a golf-club handshake.The horror lay in their absolute lack of pulse. While lives were being incinerated, they sat in a state of meditative greed, their hands steady as they signed the warrants for our ruin. They were vultures in pinstripes, waiting for the silence to grow heavy enough to start the feast. They didn't just want the money; they wanted the submission of the truth. They viewed the law not as a shield for the weak, but as a garrote they could tighten with a polished, apologetic smile.By the time they were done, they hadn't just stolen our assets—they had attempted to erase our witness, leaving nothing behind but the cold, antiseptic scent of a crime that no one is allowed to name.

They moved like ghosts through a world built to protect them — a world of shell companies, secret accounts, and paperwork so dense it could suffocate the truth before it ever reached daylight. Everything they touched was wrapped in layers of “procedure” and “confidentiality,” as if those words alone could justify the damage they caused.

And then came the arbitrations.

Government‑endorsed, they told us. Independent. Fair. Transparent. Words that now feel like a cruel joke. Because what we walked into wasn’t justice — it was theatre. A performance staged to look legitimate while the real decisions were being made somewhere else entirely.

You could feel the corruption in the air, like a cold draft under a locked door. Documents vanished. Evidence was withheld. Telstra’s misconduct was treated as an inconvenience rather than the central crime. And the people who were supposed to protect us — the arbitrator, the consultants, the so‑called watchdogs — behaved as if their job was to shield Telstra, not to uncover the truth.

That’s when I realised the real danger wasn’t the corruption itself. It was how normal it all seemed to them. How routine. How deeply embedded in the system?

The consequences weren’t just personal. They were national. When public officials can hide behind intermediaries, when corporations can manipulate government‑endorsed processes, when truth can be buried under paperwork and polite smiles — the rule of law becomes nothing more than a slogan.

Gaslighting

Psychological manipulation

Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation in which the abuser attempts to sow self-doubt and confusion in the victim's mind, i.e., you do not have a telephone problem. Our records show you are the only customer complaining when the documents show the situation the person is complaining about is systemic. Typically, gaslighting methods are used to seek power and control over the other person by distorting reality and forcing them to question their judgment and intuition.

And that’s what happened to us in the COT arbitrations.

We weren’t just fighting Telstra. We were fighting a network — a quiet, well‑connected, well‑protected network — that operated beneath the surface of Australian society. A network that treated justice as a nuisance and people like us as obstacles to be managed. What they did wasn’t just unfair. It was sinister.

Check out my latest book, "Around The World In 80 Dishes...and a few disasters", available for the modest price of $5.99 AUD on my website

https://www.promoteyourstory.com.au/.

Why Some Evidence Appears More Than Once

As you navigate through the various mini-reports and narratives on absentjustice.com, you will notice that certain segments, exhibits, and images reappear, sometimes multiple times. This is no accident; it is a deliberate choice. When you reach the bottom of this home page, you will note that there are twelve chapters, marked as Telstra-Corruption-Freehill-Hollingdale & Page to The Promised Documents Never Arrived.

Each of these twelve chapters will seamlessly build upon the narrative introduced on the absentjustice.com home page, providing an engaging continuation of the storyline. The subsequent twelve chapters will function as document storage facilities, each containing a treasure trove of intriguing mini-stories that captivate the reader's imagination. These mini-stories, while distinct and self-contained, will enrich the overall experience by offering diverse perspectives and insights that enhance the overarching themes presented in earlier chapters.

For over thirty years, government bureaucrats who protected Telstra—along with the arbitrator and the agencies that complicity enabled Telstra’s relentless attacks on our group—have relied on a sinister strategy of repetition, obstruction, and silence to bury the truth. Their plan was chillingly simple: drown out the facts, exhaust the victims, and hope the public remains oblivious to the overarching pattern. In response, I have had to unyieldingly demonstrate that what happened to the COT Cases was not merely a one-off mistake or a bureaucratic misstep. It was a system—a treacherous machinery of protection that allowed Telstra to thrive like a cancer, spreading its malign influence throughout every layer of the arbitration process.

Revisiting the same evidence is crucial for readers to fully grasp the deep-rooted extent of this misconduct. Telstra’s own documents lay bare how the arbitration system was twisted—not to reveal the truth, but to suffocate it. Each repeated exhibit exposes another thread in a web of deceit, and each recycled image reveals yet another glimpse of a pattern of behaviour that has resurfaced over the years, across claimants, and at every stage of the process.

This story cannot be understood through isolated examples. It must be unravelled through the recurrent signs of institutional decay—identical lies, nefarious tactics, and insidious cover-ups that emerge with chilling regularity. Only by recognising these patterns can readers begin to comprehend the nightmare we, the Casualties of Telstra, endured. Our attempts to challenge the corrupt telecommunications services imposed on our small businesses were met not with fairness or justice but with discrimination and contempt. We sought nothing more than the same treatment afforded to other Australian enterprises. Instead, we were ensnared in a system that consistently failed us—a calculated betrayal hidden beneath layers of corruption, deceit, and manipulation.

The COT Saga Begins

It is absolutely crucial for visitors to absentjustice.com to understand the deeply troubling revelations on pages 5163 through to 5169. These pages expose a shocking betrayal: millions upon millions of dollars in public funds were systematically pilfered by Telstra employees, as documented in the official Senate Hansard – Parliament of Australia. This was the corporation that the COT Cases—a courageous group of small business operators—were forced to confront in their desperate struggle for justice.

“Problems highlighted by Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp operator Alan Smith, with the Telecom network have been picked up on by not only other disgruntled customers but Federal politicians. Having suffered a faulty telephone service for some five years, Mr Smith’s complaints had for some time fallen on deaf ears, but it now seems people are standing up and listening. Federal Member for Wannon, David Hawker, described the number of reports of faulty and inadequate telephone across Australia as alarming. Mr Hawker said that documents recently presented to him showed that the problems people had been experiencing Australia wide had been occurring repeatedly in the Portland region.” (See Cape Bridgewater Chronology of Events File No -17)

The pressure on all four COT cases was immense, with TV and newspaper interviews and our continuing canvassing of the Senate. The stress was telling by now, but I continued to hammer for a change in rural telephone services. The Hon David Hawker MP, my local Federal member of parliament, had been corresponding with me since 26 July 1993.

“A number of people seem to be experiencing some or all of the problems which you have outlined to me. …

“I trust that your meeting tomorrow with Senators Alston and Boswell is a profitable one.” (See Arbitrator File No/76)

The Hon David Hawker MP, my local Federal Member of Parliament, corresponded with me from 26 July 1993.

On 18 August 1993, The Hon. David Hawker MP wrote to me again, noting:

“Further to your conversations with my electorate staff last week and today I am enclosing a copy of the correspondence I have received from Mr Harvey Parker, Group Managing Director of Commercial and Consumer division of Telecom.

“I wrote to him outlining the problems of a number of Telecom customers in the Western Districts, including the extensive problems you have been experiencing.” (Arbitrator File No/77)

How could the Telstra technicians, fully aware of the truth behind my claims, choose to lie under oath in their nine individual witness statements to the arbitrator assigned to assess my arbitration claims? They deceitfully asserted that Telstra was providing me with superior telephone service compared to most businesses in my area. Yet their own notes revealed a damning reality: the business was in crisis, plagued by crippling phone problems that they knew were destroying our operations.

In the shadowy depths of Portland's technological landscape, a treacherous transition unfolded. The antiquated RAX unmanned roadside telephone switching service, once a lifeline for businesses, was abruptly replaced by the sleek yet sinister Ericsson AXE telephone system. Just 18 kilometres from the haunting shores of Cape Bridgewater, this upgrade was heralded as progress, but it soon revealed its malevolent nature.

A Matter of Public Interest

The ninth remedy pursued, and The twelfth remedy pursued

Transcripts from the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) dated 8 October 2008 (No V2008/1836) reveal significant testimony provided by me under oath. I informed two government attorneys and a senior member of the AAT panel that I was actively seeking access to a series of freedom of information documents that Telstra had withheld during the critical arbitration discovery process from 1994. My primary objective was to compile a comprehensive and factual narrative that would illuminate the issues surrounding my case and potentially open doors for other similar cases—fewer than sixteen in total—that could prompt the Senate to advocate for a thorough government investigation into the validity of my claims, particularly regarding the arbitrator Dr. Gordon Hughes, and the two Telecommunications Industry Ombudsmen, namely Warwick Smith (Australia's first TIO) and John Pinnock (Australia's second appointed TIO).

During the AAT hearing, I disclosed a crucial detail: unbeknownst to me, the government had concealed AUSTEL Adverse Findings referenced as AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings from both the arbitrator and me in March 1994, leading up to my arbitration on 21 April 1994. Alarmingly, these findings were provided to Telstra just six weeks before I signed my arbitration agreement. This transfer of information was strategically timed to assist Telstra in mounting a defence against my claims regarding the persistent problems I experienced with telephone and fax services, issues that continued even on the day the information was provided to them. And more importantly, for nine more years after the completion of my arbitration, referenced as Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story and Chapter 5 Immoral - Hypocritical Conduct.

It appeared that the government believed it was imperative to prevent me from substantiating my claims. It was not until November 2007—twelve years after the government initially supplied these AUSTEL Adverse Findings to Telstra—that I received access to this critical document. By this point, the usefulness of the findings had diminished significantly, as they were now five years past the six-year statute of limitations for filing an appeal against my award.

A thorough examination of this report, which is attached here and available on the absentjustice.com homepage, as well as throughout this website and in the 3,600 evidence files that can be downloaded freely, may lead an impartial observer to conclude that the government has clearly breached its obligations to me as a citizen of Australia. This breach appears to stem from a discriminatory practice favouring Telstra, a corporation wholly owned by the Australian government—representing the collective interests of the Australian people—during that significant period in March 1994.

At the conclusion of the findings, which began in February 2008 and finished on 3 October 2008, Justice Friedman stated in front of the two government attorneys and me, as I represented myself along with several guests in the AAT chambers:

“Let me just say, I don’t consider you, personally, to be frivolous or vexatious – far from it.

“I suppose all that remains for me to say, Mr Smith, is that you obviously are very tenacious and persistent in pursuing the – not this matter before me, but the whole – the whole question of what you see as a grave injustice, and I can only applaud people who have persistence and the determination to see things through when they believe it’s important enough.”

"COT" Case Strategy

As shown on page 5169 in Australia's Government SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia Telstra's lawyers Freehill Hollingdale & Page devised a legal paper titled "COT" Case Strategy (see Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C) instructing their client Telstra (naming me and three other businesses) on how Telstra could conceal technical information from us under the guise of Legal Professional Privilege even though the information was not privileged.

This COT Case Strategy was to be used against me, my named business "Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp/Alan Smith", and the three other COT case members, Ann Garms, Maureen Gillan and Graham Schorer, and their three named businesses. Simply put, we and our four businesses were targeted more than eight months before our arbitrations commenced.

What I did not know, when I was first threatened by Telstra in July 1993 and again by Denise McBurnie in September 1993, that if I did not register my telephone problems in writing with Denise McBurnie, then Telstra would NOT investigate my ongoing telephone fault complaints is that this "COT Case Strategy" was a set up by Telstra and their lawyers to hide all proof that I genuinely did have ongoing telephone problems affecting the viability of my business.

The relentless demand to document every single telephone fault and report these trivial daily issues to Denise McBurnie before Telstra would even condescend to address them was maddening. It was no wonder I was suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD); the very act of having to funnel complaints through Telstra's legal labyrinth before they would deign to investigate was a recipe for depression, warping anyone’s thought processes.

This document confirms that AUSTEL has initiated an investigation into my ongoing telephone issues. This investigation contradicts the statements made by Freehill Hollingdale & Page, Telstra's arbitration lawyers, as well as Denise McBurnie's attempts to minimise my ongoing telephone problems. The following AUSTEL findings on their investigations support my claims against Telstra, particularly regarding the issues outlined between Points 2 and 212 in AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings.

Hovering your cursor over the image of the "Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Residence" below will direct you to a document dated March 1994, referred to as AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings. I informed AUSTEL's Chairman, Robin Davey, and AUSTEL's General Manager of Consumer Affairs, John MacMahon, that Denise McBurnie from Freehill Hollingdale & Page, through whom I was required to register my phone faults before Telstra would investigate, was contradicting the complaints I made over the phone and downplaying the seriousness of the issues I continued to face. At that time, both Mr Davey and Mr MacMahon requested that I report my 008 and fax billing problems directly to AUSTEL, which I did from January 27, 1994, to October 3, 1995 (see Open letter File No/46-A to 46-l)

Stop the COT Cases at all costs

Worse, however, the day before the Senate committee uncovered this COT Case Strategy, discussed above, they were also told under oath, on 24 June 1997 see:- pages 36 and 38 Senate - Parliament of Australia from an ex-Telstra employee turned -Whistle-blower, Lindsay White, that, while he was assessing the relevance of the technical information which the COT claimants had requested, he advised the Committee that:

Mr White "In the first induction - and I was one of the early ones, and probably the earliest in the Freehill's (Telstra’s Lawyers) area - there were five complaints. They were Garms, Gill and Smith, and Dawson and Schorer. My induction briefing was that we - we being Telecom - had to stop these people to stop the floodgates being opened."

Senator O’Chee then asked Mr White - "What, stop them reasonably or stop them at all costs - or what?"

Mr White responded by saying - "The words used to me in the early days were we had to stop these people at all costs".

Senator Schacht also asked Mr White - "Can you tell me who, at the induction briefing, said 'stopped at all costs" .

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble, Peter Riddle".

Senator Schacht - "Who".

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble and a subordinate of his, Peter Ridlle. That was the induction process-"

Mr White's statement highlights a significant fact: he specifically identified me as one of the five COT claimants that Telstra targeted while he was in secondment to Freehill Hollindale & Page. Their efforts were focused on preventing us five from successfully establishing our case against Telstra.

Please note: Freehill Hollingdale & Page are now trading under the name of Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne.

It was not in Mr Joblin's hand

It bore no signature of the psychologist

It is important to note that when Ian Joblin reviewed the Cape Bridgewater Bell Canada tests, he observed that 13,590 test calls had been generated at various times during business hours over a five-day period, and all were successfully answered by the testing machine. My response to this was to laugh—not mockingly, but in a way that surprised Mr Joblin. I explained to him that NONE of the 13,590 test calls could have been made, which made him angry at Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now trading as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne the lawyers for Telstra, who had provided him with this report. Mr Joblin stated that he would address this falsehood in the attached witness statements supporting his report.

As shown in government records, the government assured the COT Cases (see point 40 Prologue Evidence File No/2), Freehill Holingdale & Page / Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne) would have no further involvement in the COT issues; the same legal firm that, when they provided Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist's witness statement to the arbitrator, only signed by Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehill's. It bore no signature of the psychologist.

Did Maurice Wayne Condon remove or alter any reference to what Ian Joblin had initially written about me being of sound mind?

On 21 March 1997, twenty-two months after the conclusion of my arbitration, John Pinnock (the second appointed administrator to my arbitration), wrote to Telstra's Ted Benjamin (see File 596 → AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) asking:

1...any explanation for the apparent discrepancy in the attestation of the witness statement of Ian Joblin .

2...were there any changes made to the Joblin statement originally sent to Dr Hughes compared to the signed statement?"

The fact that Telstra's lawyer, Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehills / Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne, signed the witness statement without the psychologist's signature highlights the significant influence Telstra lawyers have over the arbitration legal system in Australia.

It is now 2026, and I still have not received a response to John Pinnock's letter to Telstra dated March 21, 1997, concerning this witness statement. This letter would have been helpful for my pending arbitration appeal. The lack of response is further evidence that Telstra feels it can act with impunity against anyone who challenges its gross misconduct.

What has also shocked most people who have read several other witness statements submitted by Telstra in various other COT Cases arbitration processes, as well as mine, is that although the senate was advised that signatures had also been fudged or altered in my case, changing or altering a medically diagnosed condition to suggest I was mentally disturbed is hinging on more than just criminal conduct. Maurice Wayne Condon must have attested to seeing a signature on an arbitration witness statement prepared by Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, when no signature by Ian Joblin was on this affirmation, which is further proof that Telstra is beyond the law in Australia.

Senator Bill O’Chee expressed serious concern about John Pinnock's failure to respond to his letter dated 21 March 1997, addressed to Ted Benjamin of Telstra. This lack of response, coupled with evidence from another COT Case suggesting that statutory declarations had been tampered with by Telstra or their legal representatives during arbitration, prompted Senator Bill O'Chee to write to Graeme Ward, Telstra's regulatory and external affairs, on 26 June 1998 (refer to File GS-CAV Exhibit 258 to 323 on 26 June 1998 from, stating.

“I note in your letter’s last page you suggest the matter of the alteration of documents attached to statutory declarations should be dealt with by the relevant arbitrator. I do not concur. I would be grateful if you could advise why these matters should not be referred to the relevant police."

When I raised concerns about the alteration of documents with the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), I highlighted instances of tampering involving Telstra. In my case, 56 fax header sheets were modified and added to different reports. I provided this evidence at the suggestion of Superintendent Jeff Penrose from the Australian Federal Police, personally delivering it to the TIO office. (Refer to Exhibits 76 → AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91). Despite this, no one in the arbitration process was willing to address Telstra's actions. Included here are the statutory declaration and a note from the Deputy TIO, Sue Harlow, confirming that I personally submitted this evidence to her on May 16, 1994 (Refer to Exhibits 77→ AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91).

Also, in the above Senate Hansard on 24 June 1997 (refer to pages 76 and 77 - Senate - Parliament of Australia Senator Kim Carr states to Telstra’s main arbitration defence Counsel (also a TIO Council Member) Re: Alan Smith:

Senator CARR – “In terms of the cases outstanding, do you still treat people the way that Mr Smith appears to have been treated? Mr Smith claims that, amongst documents returned to him after an FOI request, a discovery was a newspaper clipping reporting upon prosecution in the local magistrate’s court against him for assault. I just wonder what relevance that has. He makes the claim that a newspaper clipping relating to events in the Portland magistrate’s court was part of your files on him”. …

Senator SHACHT – “It does seem odd if someone is collecting files. … It seems that someone thinks that is a useful thing to keep in a file that maybe at some stage can be used against him”.

Senator CARR – “Mr Ward, we have been through this before in regard to the intelligence networks that Telstra has established. Do you use your internal intelligence networks in these CoT cases?”

The most alarming situation regarding the intelligence networks that Telstra has established in Australia is who within the Telstra Corporation has the necessary expertise, i.e., government clearance, to filter the raw information collected before it is impartially catalogued for future use?

More importantly, when Telstra was fully privatised in 2005, which organisation in Australia was given the charter to archive this sensitive material that Telstra had been collecting about its customers for decades?

In 1997, during the same government-endorsed arbitration and mediation process, Sandra Wolfe, another COT case, encountered significant injustices concerning a bogus-type clinical psychologist who was prepared to state Sandra Wolfe was a nutter. Notably, a warrant was executed against her under the Queensland Mental Health Act (see pages 82 to 88, Introduction File No/9), with the potential consequence of her institutionalisation. It is evident that Telstra and its legal representatives sought to exploit the Queensland Mental Health Act as a means of recourse against the COT Cases in the event they were unable to prevail through conventional means. Senator Chris Schacht diligently addressed this matter in the Senate, seeking clarification from Telstra by stating:

“No, when the warrant was issued and the names of these employees were on it, you are telling us that it was coincidental that they were Telstra employees.” (page - 87)

Why has this Queensland Mental Health warrant matter and the use of questionable clinical psychologists by Telstra never been transparently investigated and a finding made by the government communications regulator?

Delve into the Sinister World of Corruption in Australia.

Government Corruption & Dirty Politics.

In the capital, people whispered that the government had slipped quietly into kleptocracy, a place where public office had become little more than a storefront for private gain. What began as rumours of dirty politics soon hardened into something far more organised — a network of officials who operated like a political machine straight out of a RICO indictment.

Everyone knew about the backhanders and kickbacks, the envelopes passed under tables to grease the wheels of bureaucracy. Some called it palm oil, others called it survival. Bills were routinely hog‑housed, rewritten in the dead of night to serve donors rather than citizens. Lobbyists roamed the halls with the confidence of owners, their “advocacy” little more than payola dressed up in legal language. In this world, a politician wasn’t elected — they were bought, sometimes openly, sometimes quietly bought off through favours, donations, or promises of future power > Senate Evidence File No 21 Senate Hansard dated 27 Feb 1998 re kick-backs and bribes <

Behind the scenes, a shadowy circle of senior bureaucrats — the so‑called Deep State — ensured that nothing threatened the arrangement. They were the guardians of continuity, the ones who kept files sealed and inquiries stalled. When scandals threatened to surface, hush money flowed like water, buying silence, loyalty, or disappearance. The press dubbed them the Dirty Dozen, a small group with outsized influence, each one skilled in the art of spin, twisting every revelation into a misunderstanding, every accusation into a partisan attack.

Deals were struck through whispered quid pro quo arrangements: a contract here, a favour there, a promise tucked into a footnote. It was a system designed not to serve the public, but to protect itself — a closed loop of power, money, and silence.

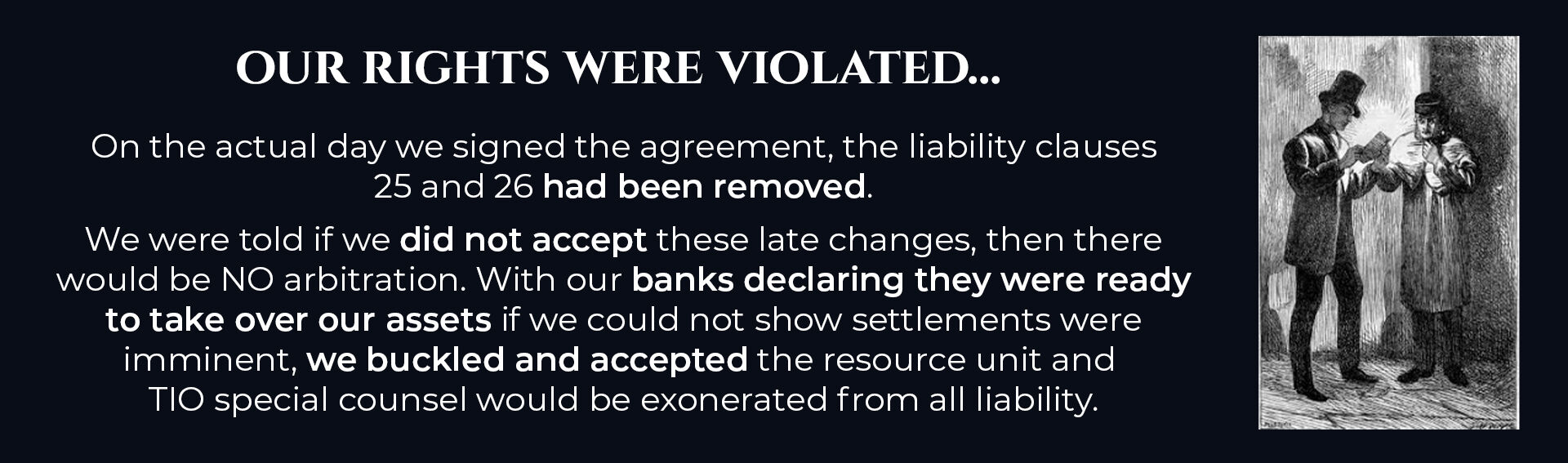

I have always maintained our lawyers thought we were signing the arbitration agreement, the first of the four COT Cases Maureen Gillan had signed two weeks before. I only agreed to clause 10.2.2. being removed. With our banks declaring they were ready to take over our assets if we could not show imminent settlements, I buckled to removing only that clause.

No matter how much pressure was applied to them, no one in their right mind would have accepted a compromise of such magnitude. Modifying clause 24 and removing clauses 25 and 26 meant we could not sue the TIO-appointed arbitration consultants (there were several) for acts of negligence. The legal counsel to the arbitration and the professional consultants were bulletproof. They could freely do whatever they liked when they liked, and there was nothing anyone could do. This website, absentjustice.com, shows this is precisely what happened.

On the day we signed the arbitration agreement (see Part 2 → Open letter File No 54-B), clause 10.2.2 and the $250,000.00 liability caps in clauses 25 and 26 had been removed, and clause 24 had been modified. We were informed that there would be no arbitration if we did not accept these last-minute changes. Additionally, we were told that our lawyers had been notified of these changes. However, there is no record of our lawyers accepting these modifications

As revealed in Part 2, Dr Gordon Hughes, the soon-to-be-appointed arbitrator, orchestrated the exoneration of his arbitration technical and financial advisor from any negligence claims related to our arbitration. It wasn’t until years after the arbitration concluded that we uncovered the troubling truth: Dr Hughes had been embroiled in a Federal Court action against Telstra, with the claimant being none other than Graham Schorer, the spokesperson for the COT Cases in our current arbitration. In that prior case, Dr Hughes represented Schorer, and, as documented in Graham Schorer's statement attached to Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest, he withheld crucial documents from Schorer during this Federal Court Action.

Was Dr Hughes planning to repeat this treachery four years later? Those who delve into "Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct" and examine the conflict-of-interest exhibit will quickly grasp that Dr Hughes was not the principal arbitrator responsible for reviewing the arbitration documents. That critical task was covertly handed over to the arbitration financial consultants by Warwick Smith, the first appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, who colluded with Telstra to ensure this orchestrated deception.

This clandestine agreement stipulated that if the arbitration consultants—who had been exonerated from all liability—declared a document irrelevant to the arbitration, it would remain hidden from both the arbitrator and the claimants. The depths of this corruption and betrayal are nothing short of alarming.

In 2025, Dr Gordon Hughes is Principal Lawyer of Davies Collison Cave's Lawyers Melbourne → https://shorturl.at/L4tbp

The first shocking indication that something deeply corrupt was at play struck me when the vital documents I had requested under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act disappeared as if they were never meant to be seen. They weren’t merely misplaced or delayed; they had been deliberately eradicated, erased from existence to shield the truth. The scant documents that I did receive were so heavily redacted that they resembled a tangled mess of obfuscation, and accompanied by bewildering schedules that attempted to outline which fragments of my FOI request they addressed—an infuriating game of deception.

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

It is clear from exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

Does Telstra expect the AFP to accept that, every time this officer left the Portland telephone exchange, the alarm bell set to broadcast my telephone conversations throughout the exchange was turned off? What was the point of setting up equipment connected to my telephone lines that only operated when this person was on duty?

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

Leading up to the signing of the COT Cases arbitration, on 21 April 1994, AUSTEL wrote to Telstra on 10 February 1994 stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

This internal, dated 25 February 1994, is a Government Memo confirming that the then-Minister for Communications and the Arts had written to advise that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (AFP Evidence File No 4)

A System Built on Silence

📠 The Vanishing Faxes: A Calculated Disruption

Exhibits 646 and 647 (see ) clearly show that, in writing, Telstra admitted to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

This particular Telstra technician, who was then based in Portland, not only monitored my phone conversations but also took the alarming step of sharing my personal and business information with an individual named "Micky." He provided Micky with my phone and fax numbers, which I had used to contact my telephone and fax service provider (please refer to Exhibit 518 → AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541 , FOI folio document K03273.

To this day, this technician has not been held accountable or asked to clarify who authorised him to disclose my sensitive information to "Micky." I am perplexed as to why Dr Gordon Hughes did not pursue any inquiries with Telstra regarding this local technician’s actions. Specifically, why was he permitted to reveal my private and business details without any apparent oversight or justification?

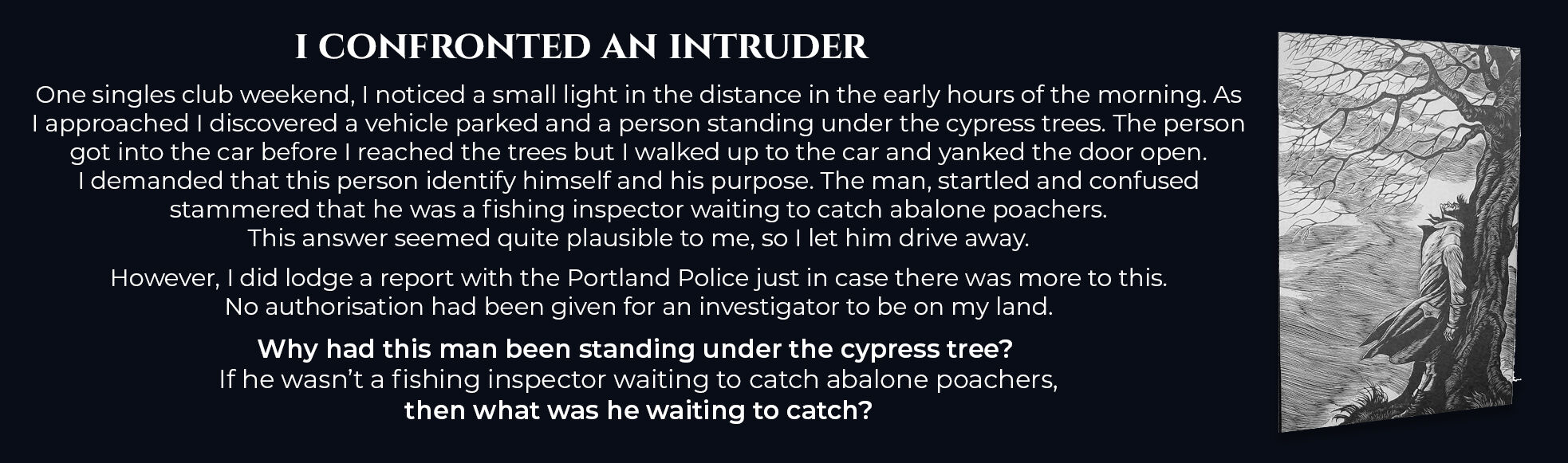

PLEASE NOTE: I had dedicated over six years of my life as a volunteer at the Portland Tourist Office when a now-resigned Telstra technician, known as Gordon, joined our team. Prior to his arrival, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) had received written information from management indicating that he had been listening to my private telephone conversations without my knowledge or consent. The same Gordon who was the go-between for this "Micky" fellow.

One evening, I found myself in a heated confrontation with Gordon, sitting across a sturdy table from him. My anger was palpable, coursing through me like wildfire. If the table hadn’t been there to separate us, I might have lost control and struck him with my briefcase. Unable to bear the tension any longer, I left that night and never set foot in the Tourist Office again.

Gordon’s involvement didn’t stop there. He was later summoned to the council chambers while I was present to discuss local matters as an honorary spokesperson for a significant development project. Following that tense encounter, I resolved never to return to the Council Chambers again. According to the transcripts from the Australian Federal Police, Gordon had been complicit in connecting an alarm system at the Portland telephone exchange, which allowed him to tap into my phone conversations during his shifts.

Senator Chris Schacht, Senator Kim Carr, and The Hon. David Hawker, Speaker of the House of Representatives, are aware of my situation. I was charged in Portland Court for putting a wrestling hold, a "Full Nelson," on a sheriff and his aides. They were in the process of removing essential industrial kitchen equipment from my holiday camp due to my overdue hire fees from the past six months. Had I not intervened, I would have faced the devastating loss of my holiday camp.

Navigating the challenges of phone tapping and fax hacking while managing a telephone-dependent business in the close-knit Portland community proved to be an uphill battle for both the other COT Cases and me. However, I was not entirely alone in my struggles. The Hon. Peter Costello, Australia’s Federal Treasurer, reached out to me, extending a hand of moral support, as did several other government ministers who recognised that the story of the COT involved complexities from multiple perspectives.

However, on this occasion, this snooping was still in operation three years after my arbitration was completed; it was my letter to The Hon Peter Costello that was hacked into, as Exhibit-10-C below shows.

Exhibit 10-C → File No/13 in the Scandrett & Associates report Pty Ltd fax interception report (refer to (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) confirms my letter of 2 November 1998 to the Hon Peter Costello Australia's then Federal Treasure was intercepted scanned before being redirected to his office. These intercepted documents to government officials were not isolated events, which, in my case, continued throughout my arbitration, which began on 21 April 1994 and concluded on 11 May 1995. Exhibit 10-C File No/13 shows this fax hacking continued until at least 2 November 1998, more than three years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

Firstly, Mr Rumble was a senior government lobbyist and a Telstra employee who actively obstructed the provision of essential arbitration discovery documents that the government was legally obligated to provide under the Freedom of Information Act. This obligation was contingent on my signing an agreement to participate in a government-endorsed arbitration process. By imposing this condition, Mr Rumble undermined a legally established protocol, effectively manipulating the process for his benefit and jeopardising my legal rights.

Secondly, I discovered that Mr Rumble had a substantial influence over the arbitrator, leading to the unauthorised early release of my arbitration interim claim materials. This premature revelation directly conflicted with the timeline stipulated in the arbitration agreement that Telstra and I had formally signed. Specifically, Telstra gained access to my interim claim document 5 months earlier than permitted under the agreed terms. This breach of protocol violated the integrity of the arbitration process and gave Telstra an unfair advantage in its response to my claims.

According to the rules governing our arbitration process, Telstra was given 1 month to respond to my final claim once it was submitted in writing. Furthermore, the arbitrator was only authorised to release my final claim to Telstra once it was officially confirmed to be complete. The five-month delay in submitting my claim in November 1994 was primarily attributable to Mr Rumble's deliberate withholding of critical technical information.

The Dark Underbelly

As a horrifying reflection of the dark underbelly of our system, the comments I publish on absentjustice.com might seem unbelievable at first glance, yet they echo the most tragic and treacherous storylines ever portrayed in film. Years ago, I read a book exposing the deception inside institutions for the insane — how innocent people were locked away, abused, silenced, and destroyed simply because exposing the truth would have threatened those in power. That same pattern, that same cruelty, has followed the COT Cases for more than three decades. In two cases that I know of, Telstra even provided false information to the arbitration-appointed psychologists who were assessing the mental health of the claimants. In my own case — as shown later in this narrative — Telstra’s lawyers, Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now trading as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne), fed false information to Ian Joblin, the clinical psychologist assigned to assess my mental state. They went further still, tampering with his findings and attesting that his witness statement bore his signature when no such signature existed on the version sent to the arbitrator.

Imagine a tale centred around a hero or heroine whose unwavering innocence leads them into the murky depths of a nightmarish existence — unjustly imprisoned for years while a twisted web of lies and deceit irreparably alters the course of their life. We cheer when justice triumphs in stories like these, but for many of us, myself included, such endings remain cruel figments of fiction.

For over thirty agonising years, countless individuals — including me — have been labelled as Casualties of Telstra and trapped in our own tragic saga, a relentless wait for redemption that never arrives. In April 1998, Sue Laver, a Senior Telstra Executive, held damning evidence that could have unravelled this entire nightmare. She knew Telstra had misled the Senate by providing falsified documents about my case — a calculated act designed to bury the truth beneath layers of corruption.

When the Senate demanded answers under oath about Bell Canada International’s testing of the Cape Bridgewater exchange, Telstra chose deception over honesty (See Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2). What we need from Sue Laver in 2026 is a simple act of courage: an admission that Telstra knowingly supplied false information regarding my BCI claims when transparency with the Senate was not optional. That deception was contempt of the Senate. It was a criminal act.

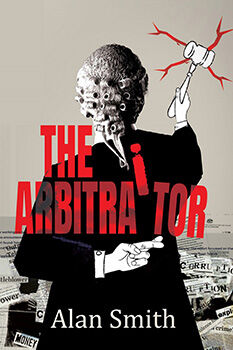

This narrative is not just a personal account; it is a grotesque nightmare, a cinematic tragedy that has haunted us for decades. Without the evidence laid out on my website, no one would believe the horrors described here. My book, "The Arbitraitor", exposes these dark realities in full, revealing the grotesque injustices we endured and the truth that has been buried for far too long.

I also shared this evidence with the Canadian government, demonstrating the corruption within some of Canada’s larger telecommunications companies. Their reply — shown below — confirms that this story reaches far beyond Australia’s borders.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

The documents I uncovered showed that if I had accessed this information during my arbitration — when I rightfully requested it under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act — or had received it during my ongoing appeal process, which the Canadian Government was morally trying to assist me with, it would have been enough to overturn the unjust dismissal of my claims. This information had the power to expose Telstra’s unlawful use of Bell Canada International’s testing and would have significantly strengthened my position in the pending appeal. The entire situation reflects corruption and a cover‑up so blatant that it forces me to question the integrity of those responsible for ensuring fairness in the arbitration process.

This narrative is not just a personal tale; it is a grotesque nightmare, a cinematic tragedy that has haunted us for decades. With the evidence laid out on my website — without which no one would believe the horrors described — we stand on the brink of exposing a reality so corrupt and treacherous that it demands attention. My book, The Arbitraitor, delves deep into these dark truths, revealing the injustices we endured and perhaps finally leading us toward the closure we have long sought.

In the end, it was not only the Canadian Government that recognised the seriousness of what had occurred. Another Canadian company, the DMR Group, also attempted to assist me in exposing the Bell Canada International fraud. Their willingness to engage — despite Australian authorities' refusal — stands as a stark reminder of who sought justice and who worked tirelessly to bury it.

I invite you to explore the revised edition of this book, The Arbitraitor, where I expose some of the most shocking and corrupt cases of abuse of office imaginable. In these scandals, no caution was observed before the arbitrations even began. The appointed arbitrators shamelessly manipulated the arbitration agreements to benefit their own consultants, revealing a web of collusion and deceit. The negligence demonstrated by these professionals is alarming, and I hold them fully accountable for their roles in this sinister charade. They knew the Bell Canada International Tests were fundamentally flawed, yet they still allowed Telstra to use the deficient tests to support their arbitration defence.

I invite you to explore the revised edition of this book, The Arbitraitor, where I expose some of the most shocking and corrupt cases of abuse of office imaginable. In these scandals, no caution was observed before the arbitrations even began. The appointed arbitrators shamelessly manipulated the arbitration agreements to benefit their own consultants, revealing a web of collusion and deceit. The negligence demonstrated by these professionals is alarming, and I hold them fully accountable for their roles in this sinister charade. They knew the Bell Canada International Tests were fundamentally flawed, yet they still allowed Telstra to use the deficient tests to support their arbitration defence.

On 23 March 1999, after most of the COT arbitrations had been finalised and business lives ruined due to the hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees to fight Telstra and a very crooked arbitrator, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Most Disturbing And Unacceptable

On 27 January 1999, two months before Senator Alan Eggleston's statement to the Financial Review and after having also read my draft manuscript absentjustice.com, now called "The Arbitraitor", the same manuscript I provided Helen Handbury, Sister to Rupert Murdoch, and Senator Kim Carr wrote:

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

Clicking on the senators listed below will take you to the Senate in Parliament House, Canberra, where six Australian Senators have shockingly pointed out that Telstra has “acted as a law unto themselves” during the COT (Customer-Owned Telecommunications) arbitrations. This damning revelation exposes a sinister web of corruption that has festered unchecked.

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

If the six senators investigating this matter had known the full extent of the nefarious tactics employed by Telstra and Sue Laver—who deliberately chose to withhold crucial information about the Cape Bridgewater Bell Canada International Inc. tests from the Senate—there is no doubt that chaos would have erupted. It is infuriating to realise that while I was working diligently alongside Senator Shacht, Senator Boswell, and Senator Car—trusting individuals who had faith in Telstra—we remained blind to the fact that misinformation was being insidiously fed to the Senate committee. Had this treachery been exposed during the 1998 committee hearing, the last 28 years of hell my partner, Cathy, and I have endured would have been avoided.

Helen Handbury Reads the Manuscript