Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who manipulate the legal profession in Australia. This world is rife with treachery and deceit, where words like shameful, hideous, and treacherous barely scratch the surface of the malevolence at play. Government corruption runs rampant, and the public service is tainted by deceptive conduct that has perverted the course of justice for over two decades.

Unscrupulous, vile, and corrupt actions within the Australian government have undermined the very arbitration system it once endorsed. Instances of foreign bribery and foreign corruption infiltrated the COT arbitrations, as absentjustice.com clearly shows.

absentjustice.com and absentjustice.com.au are the two websites that sparked a deeper exploration into the world of political corruption; they stand shoulder to shoulder with any true crime story.

Exposing domestic and international fraud against the government poses significant challenges, as the following link suggests: https://www.

Blowing the whistle

Corporate Corruption vs Immoral Corruption

10. Telstra's CEO and Board have known about this scam since 1992. They have had the time and the opportunity to change the policy and reduce the cost of labour so that cable roll-out commitments could be met and Telstra would be in good shape for the imminent share issue. Instead, they have done nothing but deceive their Minister, their appointed auditors and the owners of their stockÐ the Australian taxpayers. The result of their refusal to address the TA issue is that high labour costs were maintained and Telstra failed to meet its cable roll-out commitment to Foxtel. This will cost Telstra directly at least $400 million in compensation to News Corp and/or Foxtel and further major losses will be incurred when Telstra's stock is issued at a significantly lower price than would have been the case if Telstra had acted responsibly.

11. Telstra not only failed to act responsibly, it failed in its duty of care to its shareholders. So the real losers are the taxpayers and to an extent, the thousands of employees who will be sacked when Telstra reaches its roll-out targetÐcable past 4 million households, or 2.5 million households if it is assumed that Telstra's CEO accepts directives from the Minister".

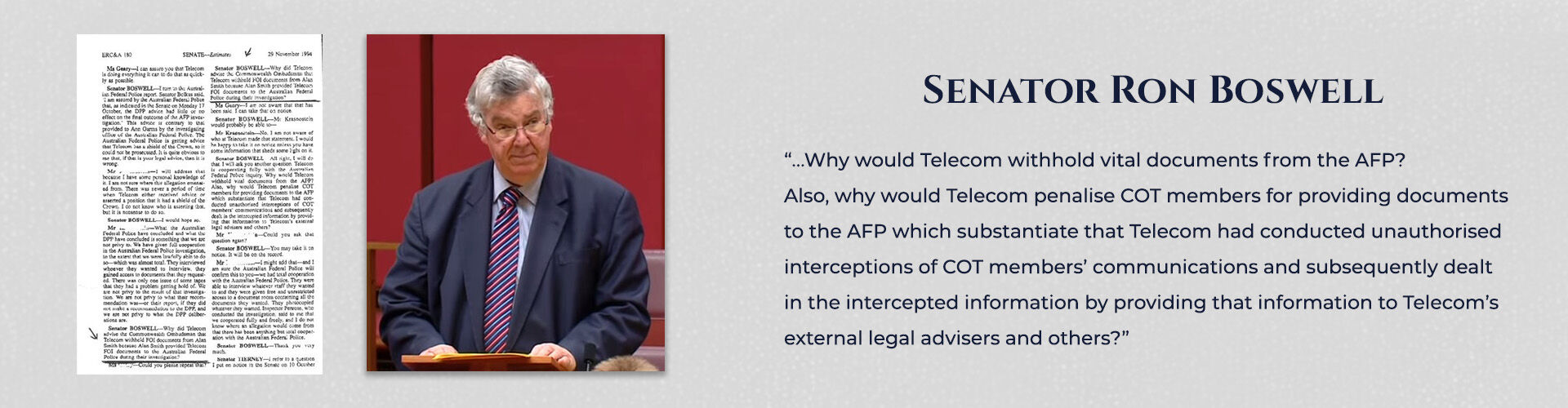

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

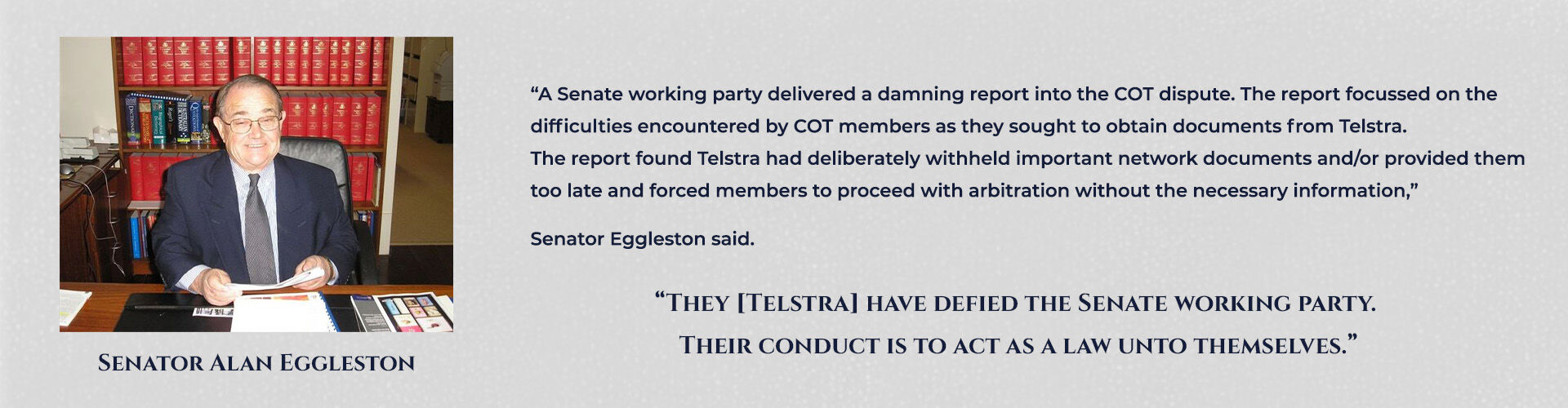

On 23 March 1999, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases, noting:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Unfortunately, because my case was settled three years prior, several other COT cases and I were unable to benefit from the valuable insights and recommendations of this investigation or from the Senate. Out of the twenty-one final arbitration and mediation cases, only five received punitive damages, along with their originally withheld FOI documents.

Don't forget to hover your mouse over the following images as you scroll down the homepage. → →

I urge all visitors to absentjustice.com to read "The first remedy pursued" and confront a chilling truth encapsulated in Simon Wiesenthal's haunting words:

I urge all visitors to absentjustice.com to read "The first remedy pursued" and confront a chilling truth encapsulated in Simon Wiesenthal's haunting words: “In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

There is no amendment attached to any agreement signed by the first four COT members that allows the arbitrator to conduct arbitrations entirely outside the established arbitration procedure. Additionally, it was not stated that the arbitrator would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. This was the main issue I discussed with Laurie James and then with John Pinnock after completing my arbitration in May 1995. How can the arbitrator and the TIO continue to rely on a confidentiality clause in our arbitration agreement when that agreement did not specify that the arbitrator would have no control because the arbitration was conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures?

In February 1996, while Hughes and Pinnock were weaving a complex web of deceit to mislead Lauria James about my claims and those of Garry Ellicott—a Senior Detective Sergeant in the Queensland Police and a former National Crime Authority officer—Telstra was carrying out a sinister plot. They tampered with evidence related to my claim after it left my premises, introducing a damaging substance to undermine an investigation into their own corrupt practices. This fraudulent act, now referred to as "Tampering with Evidence," was a calculated move by Telstra to deceive the arbitrator into believing that I had no ongoing telephone issues impacting my business.

In 2026, Dr Gordon Hughes is Principal Lawyer of Davies Collison Cave's Lawyers Melbourne → https://shorturl.at/L4tbp

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government-owned Australia's telephone network and the communications carrier, Telecom (today privatised and called Telstra). Telecom held a monopoly on communications and allowed the network to deteriorate into disrepair. Instead of our very deficient telephone services being fixed as part of our government-endorsed arbitration process, which became an uneven battle we could never win, they were not fixed as part of the process, despite the hundreds of thousands of dollars it cost the claimants to mount their claims against Telstra. Crimes were committed against us, and our integrity was attacked and undermined. Our livelihoods were ruined, we lost millions of dollars, and our mental health declined, yet those who perpetrated the crimes are still in positions of power today. Our story is still actively being covered up.

For more than thirty years, I’ve found myself ensnared in a web of bureaucratic machinations that relentlessly assert their own integrity while artfully bending rules, withholding crucial evidence, and shielding those whose reputations hinge on maintaining a façade of respectability. What started as a seemingly simple quest to rectify a faulty telephone service morphed into a harrowing confrontation with a network of corruption and institutional treachery. My journey is not simply a personal narrative of frustration or loss; it is a chilling account of how truth becomes perilous when it threatens the powerful, how ordinary citizens are left to fight treacherous battles they never asked for, all because they refuse to succumb to the injustice around them.

One of the most devastating examples of government deception and unconscionable conduct in Australia’s recent history was exposed through the Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme, which delivered its findings in 2023. The Robodebt program, introduced in 2015, used an automated debt‑recovery system that unlawfully issued debt notices to hundreds of thousands of Australians — many of them vulnerable, unemployed, disabled, or already struggling to survive. The scheme reversed the burden of proof, forcing innocent people to prove they did not owe money, even when the government had no lawful basis for claiming the debts in the first place.

The Royal Commission found that senior public servants, departmental lawyers, and ministers were repeatedly warned that the scheme was illegal, inaccurate, and harmful, yet allowed it to continue for years. Internal documents revealed that officials ignored legal advice, concealed critical information, and misled oversight bodies. The consequences were catastrophic. People lost homes, lost savings, lost mental stability — and in several tragic cases, lost their lives after receiving aggressive, incorrect debt notices that pushed them into despair.

The Commission described the conduct behind Robodebt as “cruel,” “dishonest,” and “a shameful chapter in public administration.” It shattered public trust because it showed that a government could knowingly operate an unlawful system, target its own citizens, and then attempt to hide the truth until the evidence became impossible to suppress. For many Australians, Robodebt was not just a policy failure — it was a betrayal of the most basic expectation citizens have of their government: that it will act lawfully, ethically, and with a duty of care toward the people it serves.

What makes the scandal so disturbing is that public servants inside the British Post Office knew the Fujitsu Horizon computer software was responsible for the catastrophic accounting and billing errors. Yet they continued to blame innocent sub‑postmasters, many of whom were financially ruined, prosecuted, or imprisoned.

After almost two decades, the British public—and a growing number of British politicians—have insisted that the British Post Office scandal is a matter of profound public interest and must no longer be concealed by the government, the civil service, or the Establishment. For England’s sake, this injustice demands a complete and transparent investigation. Click here to watch the Australian Channel 7 trailer for Mr Bates vs the Post Office, which aired in February 2024, and captures the scale of this national betrayal.

This pattern is painfully familiar to those of us who lived through the Australian COT arbitrations. Dr Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator appointed to oversee our cases, refused to allow his own technical consultants the additional time they needed to diagnose the ongoing faults in Telstra’s Ericsson billing software. The parallels between the British Post Office scandal and the Australian Telstra scandal are unmistakable. In both cases, faulty technical equipment was at the heart of the problem, as demonstrated in this YouTube video: https://youtu.be/

The Weight of Treachery

‘During testing the Mitsubishi fax machine some alarming patterns of behaviour was noted”. This document further goes on to state: “…Even on calls that were tampered with the fax machine displayed signs of locking up and behaving in a manner not in accordance with the relevant CCITT Group fax rules. Even if the page was sent upside down the time and date and company name should have still appeared on the top of the page, it wasn’t’

During a received call the machine failed to respond at the end of the page even though it had received the entire page (sample #3) The Mitsubishi fax machine remained in the locked up state for a further 2 minutes after the call had terminated, eventually advancing the page out of the machine. (See See AFP Evidence File No 9)

A letter dated 2 March 1994 from Telstra’s Corporate Solicitor, Ian Row, to Detective Superintendent Jeff Penrose (refer to Home Page Part-One File No/9-A to 9-C) strongly indicates that Mr Penrose was grievously misled and deceived about the faxing problems discussed in the letter. Over the years, numerous individuals, including Mr Neil Jepson, Barrister at the Major Fraud Group Victoria Police, have rigorously compared the four exhibits labelled (File No/9-C) with the interception evidence revealed in Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13. They emphatically assert that if Ian Row had not misled the AFP about the faxing problems, the AFP could have prevented Telstra from intercepting the relevant arbitration documents in March 1994, thereby avoiding any damage to the COT arbitration claims.

By February 1994, I was also assisting the Australian Federal Police (AFP) with their investigations into my claims of fax interception (Hacking-Julian Assanage File No 52 contains a letter from Telstra’s internal corporate solicitor to an AFP detective superintendent, misinforming the AFP concerning the transmission fax testing process). The rest of the file shows that Telstra experienced major problems when testing my facsimile machine alongside one installed at Graham’s office.

It is essential to highlight how skilfully Mr Row avoided disclosing to the AFP the problems Telstra had experienced when sending and receiving faxes between my machine and Graham’s.

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

Leading up to the signing of the COT Cases arbitration, on 21 April 1994, AUSTEL wrote to Telstra on 10 February 1994 stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

This internal, dated 25 February 1994, is a Government Memo confirming that the then-Minister for Communications and the Arts had written to advise that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (AFP Evidence File No 4)

A System Built on Silence

📠 The Vanishing Faxes: A Calculated Disruption

Exhibits 646 and 647 (see ) clearly show that, in writing, Telstra admitted to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

This particular Telstra technician, who was then based in Portland, not only monitored my phone conversations but also took the alarming step of sharing my personal and business information with an individual named "Micky." He provided Micky with my phone and fax numbers, which I had used to contact my telephone and fax service provider (please refer to Exhibit 518, FOI folio document K03273 - ).

To this day, this technician has not been held accountable or asked to clarify who authorised him to disclose my sensitive information to "Micky." I am perplexed as to why Dr Gordon Hughes did not pursue any inquiries with Telstra regarding this local technician’s actions. Specifically, why was he permitted to reveal my private and business details without any apparent oversight or justification?

EXAMPLE 1 → Click on →

Fax Screening / Hacking Example Only

Interception of this 12 May 1995 letter by a secondary fax machine:

Whoever had access to Telstra’s network, and therefore the TIO’s office service lines, knew – during the designated appeal time of my arbitration – that my arbitration was conducted using a set of rules (arbitration agreement) that the arbitrator declared not credible. There are three fax identification lines across the top of the second page of this 12 May 1995 letter:

- The third line down from the top of the page (i.e. the bottom line) shows that the document was first faxed from the arbitrator’s office, on 12-5-95, at 2:41 pm to the Melbourne office of the TIO – 61 3 277 8797;

- The middle line indicates that it was faxed on the same day, one hour later, at 15:40, from the TIO’s fax number, followed by the words “TIO LTD”.

- The top line, however, begins with the words “Fax from” followed by the correct fax number for the TIO’s office (visible

Consider the order of the time stamps. The top line is the second sending of the document at 14:50, nine minutes after the fax from the arbitrator’s office; therefore, between the TIO’s office receiving the first fax, which was sent at 2.41 pm (14:41), and sending it on at 15:40, to his home, the fax was also re-sent at 14:50. In other words, the document sent nine minutes after the letter reached the TIO office was intercepted.

The fax imprint across the top of this letter is the same as the fax imprint described in the Scandrett & Associates report (see Open Letter File No/12

“We canvassed examples, which we are advised are a representative group, of this phenomena .

“They show that

- the header strip of various faxes is being altered

- the header strip of various faxes was changed or semi overwritten.

- In all cases the replacement header type is the same.

- The sending parties all have a common interest and that is COT.

- Some faxes have originated from organisations such as the Commonwealth Ombudsman office.

- The modified type face of the header could not have been generated by the large number of machines canvassed, making it foreign to any of the sending services.”

The fax imprint across the top of this letter, dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the 7 January 1999 Scandrett & Associates report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and ), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations. One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

It is clear from exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

The evidence within the second section of the report → File No/13) indicates that one of my faxes sent to Federal Treasurer Peter Costello was similarly intercepted, i.e.,

Exhibit 10-C → File No/13 in the Scandrett & Associates report Pty Ltd fax interception report (refer to (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) confirms my letter of 2 November 1998 to the Hon Peter Costello Australia's then Federal Treasure was intercepted scanned before being redirected to his office. These intercepted documents to government officials were not isolated events, which, in my case, continued throughout my arbitration, which began on 21 April 1994 and concluded on 11 May 1995. Exhibit 10-C File No/13 shows this fax hacking continued until at least 2 November 1998, more than three years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

On pages 12 and 13 of the transcripts from my second interview with the Australian Federal Police (AFP) on 26 September 1994, a troubling narrative unfolds under Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1. The AFP expressed concern over a returned letter I sent to Telstra in 1992, which included a handwritten notation naming a bus company, O'Meria. This company was part of my tender to transport children and members of a social club to my holiday camp.

What’s even more alarming is the revelation that Telstra’s monitoring of my communications was far more extensive and insidious than I had imagined. The AFP highlighted that documents I accessed under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act showed that the practice of collecting and disclosing parties' addresses and phone numbers had been ongoing since at least September 1992. This raises disturbing questions about the transparency and integrity of Telstra’s operations.

Even more treacherous, it became evident that this surveillance extended into 1998, a staggering six years later, with Telstra seemingly reporting my activities directly to Australia’s Treasurer, Peter Costello. This blatant intrusion into my personal and professional life speaks to a deep-seated corruption in which powerful entities manipulate information for dubious purposes while masquerading as public service. The sinister implications of this ongoing surveillance are troubling, leaving me to wonder how many others have fallen victim to such betrayal.

Open Letter File No/41/Part-One and File No/41 Part-Two)

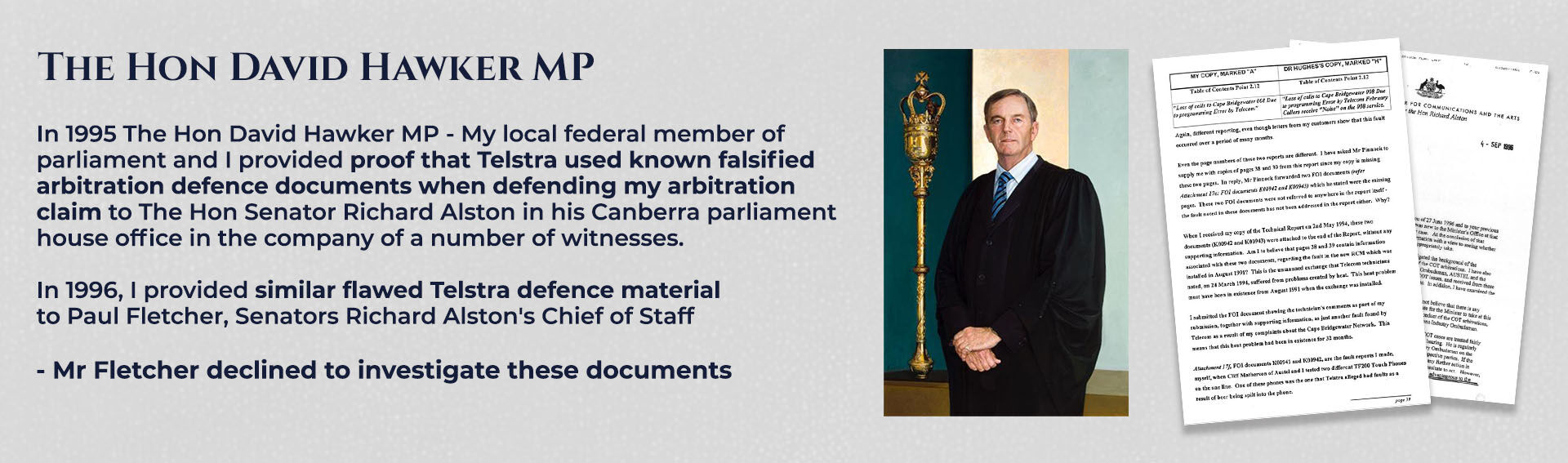

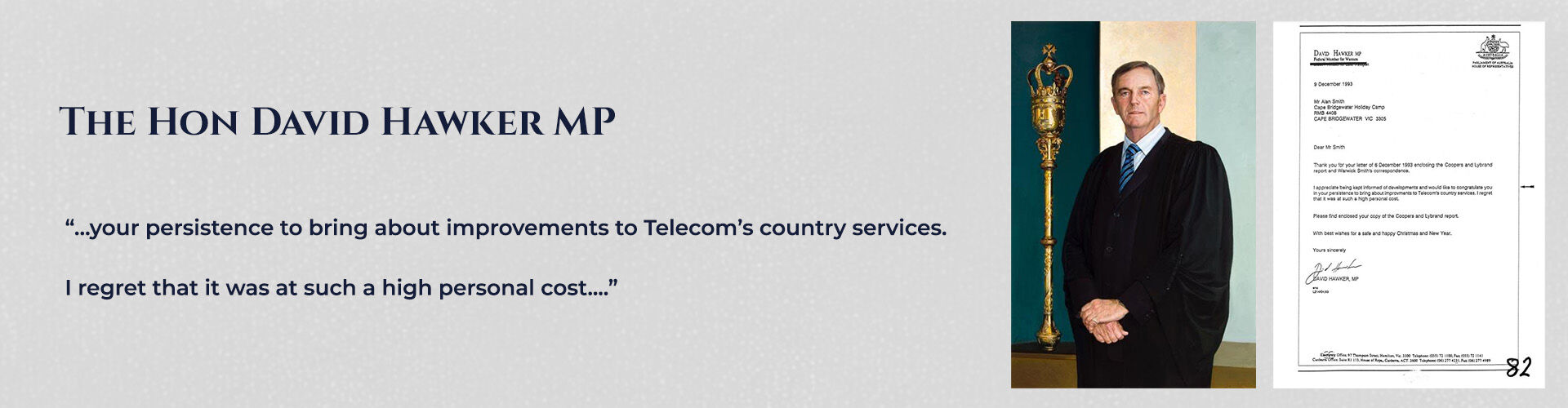

The reason for presenting Example 1 at the beginning of this story is simple: it helps readers understand that there may be far more to my story than the Australian Government has ever been willing to admit. Acknowledging the truth of what happened to me would expose the uncomfortable fact that the government should have acted in March 1996, when the newly sworn‑in Minister for Communications in the John Howard Government, Senator Richard Alston, asked The Hon. David Hawker MP and me to prepare a detailed report on my claims surrounding the COT arbitrations. I prepared that report by hand and personally delivered it to Mr Hawker, who, in turn, hand‑delivered it to Senator Alston in June 1996. Yet nothing was done — not in 1996, and not at any point in the twenty years that followed. That failure to act speaks volumes about how deficient governments can be when they choose silence over accountability.

Please continue reading this unbelievable — but entirely true — story.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

In the following sections, I will delve into the Canadian Government's involvement in my arbitration process, providing a detailed account of their role and actions. However, it is crucial to first highlight their concerns regarding my situation at the outset of this introduction to my COT story. Addressing these issues from the beginning sets the stage for a deeper understanding of the complexities and implications surrounding my case.

The Canadian government has demonstrated commendable integrity by actively addressing misleading practices, particularly in relation to Bell Canada's falsified test results. Their prompt response and concern demonstrate a commitment to honesty and accountability, prioritising the well-being of Canadian citizens. This proactive approach signifies a strong belief in the principles of transparency and fairness, which are vital for maintaining public trust.

This gross betrayal demonstrates a shocking collusion within the government, downplaying the severity of the situation by feigning that only 50 or more phone faults exist, when the reality far exceeds that number. To compound the treachery, the current Albanese government aims to grant the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) even greater authority, allowing this compromised regulator to obscure communication failures in Australia even further. Such actions cast a dark shadow over the integrity of our institutions and the trust we place in them.

The evidence that Telstra withheld 120,000 complaints from its shareholders, while only disclosing 50 or more, reveals a shocking reality. The fact that there were 120,000 complaints from Telstra customers, similar to the COT-type cases, and this information was not included in the sale prospectus constitutes gross negligence.

“Our local technicians believe that Mr Smith is correct in raising complaints about incoming callers to his number receiving a Recorded Voice Announcement saying that the number is disconnected.

“They believe that it is a problem that is occurring in increasing numbers as more and more customers are connected to AXE.” (See False Witness Statement File No 3-A)

To further support my claims that Telstra already knew how severe the Ericsson Portland AXE telephone faults were, can best be viewed by reading Folios C04006, C04007 and C04008, headed TELECOM SECRET (see Front Page Part Two 2-B), which state:

“Legal position – Mr Smith’s service problems were network related and spanned a period of 3-4 years. Hence Telecom’s position of legal liability was covered by a number of different acts and regulations. … In my opinion Alan Smith’s case was not a good one to test Section 8 for any previous immunities – given his evidence and claims. I do not believe it would be in Telecom’s interest to have this case go to court.

“Overall, Mr Smith’s telephone service had suffered from a poor grade of network performance over a period of several years; with some difficulty to detect exchange problems in the last 8 months.”

Telstra internal (Freedom of Information - FOI folio C04094) from Greg Newbold to numerous Telstra executives and discussing “COT cases latest”, states:-

“Don, thank you for your swift and eloquent reply. I disagree with raising the issue of the courts. That carries an implied threat not only to COT cases but to all customers that they’ll end up as lawyer fodder. Certainly that can be a message to give face to face with customers and to hold in reserve if the complaints remain vexacious .” GS File 75 Exhibit 1 to 88

As you will see as this story unfolds, within eighteen months of moving to Cape Bridgewater from Melbourne, my wife of twenty years, Faye, decided to leave due to the stress of managing a telephone-dependent business without a dependable phone service.

British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smith's Seaman.

British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smith's Seaman. The relentless stress of phones failing, coupled with the agonising eighteen months of watching my life savings vanish due to a business with a treacherous, unreliable phone service, was nothing short of suffocating. With mobile phones and computers still a decade away from becoming common in Australia, I felt powerless—a mere pawn in a game controlled by unseen forces. This profound lack of control over my own destiny ignited a big, unsettling change during my time in China.

Vol. 87 No. 4462 (4 Sep 1965) - National Library of Australia https://nla.gov.au › nla.obj-702601569

"The Department of External Affairs has recently published an "Information Handbook entitled "Studies on Vietnam". It established the fact that the Vietcong are equipped with Chinese arms and ammunition"

If it is right to ask Australian youth to risk everything in Vietnam it is wrong to supply their enemies. The Communists in Asia will kill anyone who stands in their path, but at least they have a path."

Australian trade commssioners do not so readily see that our Chinese trade in war materials finances our own distruction. NDr do they see so clearly that the wheat trade does the same thing."

The People's Republic of China

Murdered for Mao: The killings China ‘forgot’

The Letter, the Truth, and the Waiting

In August 1967, I found myself in a situation so precarious, so surreal, that it would etch itself into the marrow of my memory. I was aboard a cargo ship docked in China, surrounded by Red Guards stationed on board twenty-four hours a day, spaced no more than thirty paces apart. After being coerced into writing a confession—declaring myself a U.S. aggressor and a supporter of Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist leader in Taiwan—I was told by the second steward, who handled the ship’s correspondence, that I had about two days before a response to my letter might reach me. That response, whatever it might be, would be delivered by the head of the Red Guards himself.

It was the second steward who quietly suggested I write to my parents. I did. I poured myself into 22 foolscap pages, writing with the urgency of a man who believed he might not live to see the end of the week. I told my church-going parents that I was not the saintly 18-year-old they believed I was. I confessed that the woman they had so often thanked in their letters—believing her to be my landlady or carer—was in fact my lover. She was 42. I was 18 when we met. From 1963 to 1967, she had been my anchor, my warmth, my truth. I wrote about my life at sea, about the chaos and the camaraderie, about the loneliness and the longing. I wrote because I needed them to know who I really was, in case I was executed before I ever saw them again.

As the ship’s cook and duty mess room steward, I had a front-row seat to the daily rhythms of life on board. I often watched the crew eat their meals on deck, plates balanced on the handrails that lined the ship. We were carrying grain to China on humanitarian grounds, and yet, the irony was unbearable—food was being wasted while the people we were meant to help were starving. Sausages, half-eaten steaks, baked potatoes—they’d slip from plates and tumble into the sea. But there were no seagulls to swoop down and claim them. They’d been eaten too. The food floated aimlessly, untouched even by fish, which had grown scarce in the harbour. Starvation wasn’t a concept. It was a presence. It was in the eyes of the Red Guards who watched us eat. It was in the silence that followed every wasted bite.

A Tray of Leftovers and a Silent Exchange

After my arrest, I was placed under house arrest aboard the ship. One day, I took a small metal tray from the galley and filled it—not with scraps, but with decent leftovers. Food that would have gone into the stockpot or been turned into dry hash cakes. I walked it out to the deck, placed it on one of the long benches, patted my stomach as if I’d eaten my fill, and walked away without a word.

Ten minutes later, I returned. The tray had been licked clean.

At the next meal, I did it again—this time with enough food for three or four Red Guards. I placed the tray on the bench and left. No words. No eye contact. Just food. I repeated this quiet ritual for two more days, all while waiting for the response to my letter. During that time, something shifted. The Red Guard, who had been waking me every hour to check if I was sleeping, stopped coming. The tension in the air thinned, just slightly. And I kept bringing food—whenever the crew was busy unloading wheat with grappling hooks wrapped in chicken wire, I’d slip out with another tray.

To this day, I don’t know what saved me. It was certainly not the letter declaring myself a U.S. aggressor and a supporter of Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist leader in Taiwan. Maybe it was luck. Or perhaps it was that tray of food, offered without expectation, without speech, without condition. A silent gesture that said, “I see you. I know you’re hungry. I know you’re human.”

And maybe, just maybe, that was enough. British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smith's Seaman. → Chapter 7- Vietnam-Vietcong-2

Footnote 83, 84 and 169 → in a paper submitted by Tianxiao Zhu to - The Faculty of the University of Minnesota titled Secret Trails: FOOD AND TRADE IN LATE MAOIST CHINA, 1960-1978, etc → Requirements For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy - Christopher M Isett June 2021

Tianxiao Zhu's Footnotes 83:

In September 1967, a group of British merchant seamen quit their ship, the Hope Peak, in Sydney and flew back to London. They told the press in London that they quit the job because of the humiliating experiences to which they were subjected while in Chinese ports. They also claimed that grain shipped from Australia to China was being sent straight on to North Vietnam. One of them said, “I have watched grain going off our ship on conveyor belts and straight into bags stamped North Vietnam. Our ship was being used to take grain from Australia to feed the North Vietnamese. It’s disgusting.”

And here I was, twenty years later, in my Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp, gazing out at the Southern Ocean. Just a five-minute walk from where I stood in 1994, I found myself reflecting on the tumultuous journey I had endured—almost facing execution in communist China, battling in another war, this time against Telstra, the Australian government-owned entity that had unearthed my past and buried it in internal memos.

Telstra had linked it to my communications with former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser. They had documented it, discussed it, and refused to explain why.

I held the memo in my hands and felt a familiar tightness in my chest — the same tightness I had felt in 1967 when the Red Guards shouted accusations I could not disprove. But this time, the fear was different. This time, it wasn’t a foreign regime threatening me.

It was home. It was during my government-endorsed arbitration with Telstra.

Threats made and carried out under the auspices of the Supreme Court of Victoria

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no intention of submitting any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call, one of two I received from Paul Rumble, who was an arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, he issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions, I would jeopardise my access to crucial documents pertaining to the ongoing problems I was experiencing with my Ericsson AXE telephone service.

Seven official FOI requests made by me between December 1993 and the day the arbitrator handed down his formal report on 11 May 1995, concerning the Ericsson AXE installed equipment at the Portland and Cape Bridgewater exchanges that serviced my business, had not been provided by that date and have still not been provided in my two FOI requests registered in 2008 and again in 2011 with ACMA the respondants in my two the Government-Administrative Appeals Trubunal (AAT) hearings.

In unsettling terms, the documents tied to the Portland Ericsson AXE telephone exchange, along with numerous COT cases facing relentless problems with similar Telstra-installed Ericsson telephone exchange equipment, were brazenly compromised when the international giant Ericsson orchestrated a covert takeover of Australian government-endorsed arbitrations. With this treacherous sale, everything—every critical technical arbitration and mediation document from around sixteen COT processes—fell into the hands of Sweden's largest telecommunications behemoth. This foul deed was executed in broad daylight for an undisclosed sum, betraying the trust of countless citizens.

The Australian bureaucrats, puppeteers pulling the strings of our politicians, have repeatedly sacrificed their own citizens' interests, reminiscent of some of the darkest dealings during the Vietnam War. They have shamefully sold out the lives of law-abiding Australians, and to this day, not a single member of the government has the spine to admit the stark truth of this sinister betrayal.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could affect the arbitrator's decisions in my case.

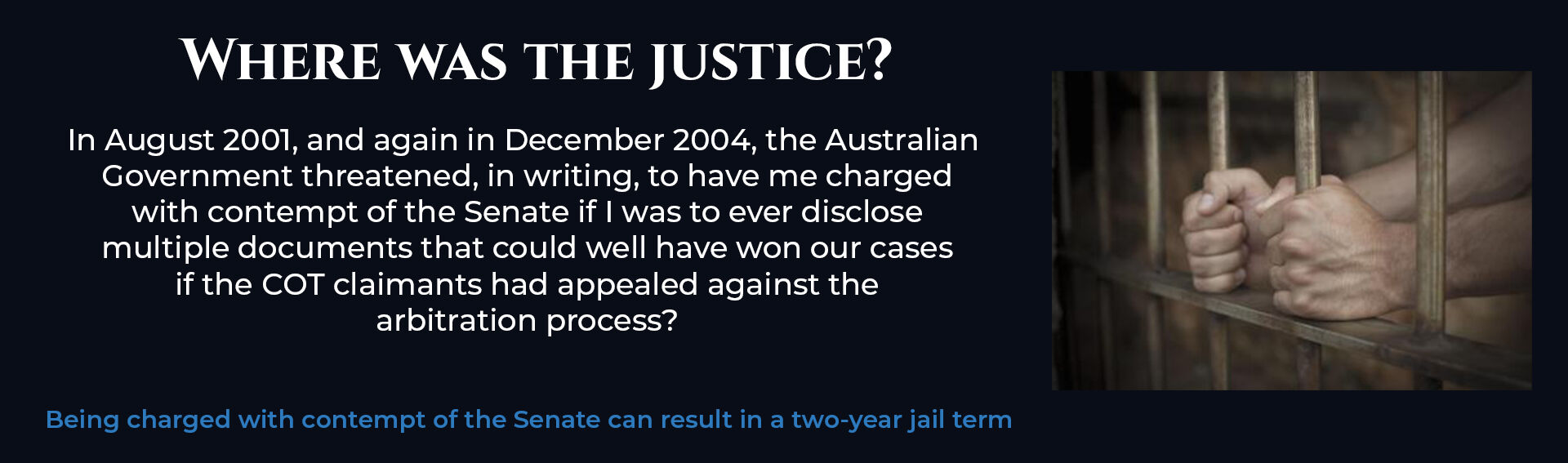

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on September 26, 1994. During this visit, they began asking probing questions about my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

When Paul Rumble stopped providing the requested documents, it was because he discovered that I was assisting the Australian Federal Police (AFP) by supplying evidence suggesting that Telstra was hacking into my faxes and telephone conversations. Senator Ron Boswell took these serious issues to the Senate.

Threats that became a reality

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

What is so appalling about this withholding of relevant Ericsson AXE telephone exchange documents is this: no one in the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman (TIO) office or the government has ever investigated the disastrous impact of this withholding on my overall submission to the arbitrator. The arbitrator and the government (at the time, Telstra was a government-owned entity) should have initiated an investigation into why an Australian citizen who had assisted the AFP in its investigations into unlawful interception of telephone conversations was so severely disadvantaged in a civil arbitration.

🎙️ Voiceover Script: “The Betrayal Beneath the Wires

In the shadows of Australia’s telecom empire, a sinister alliance was forged.

Telstra, once government-owned, buried the truth behind the COT Cases—refusing to release critical FOI documents, silencing victims, and shielding corruption.

Then came the scandal: Ericsson, under global scrutiny, quietly bought out Lane—the very consultant tasked with investigating its faulty equipment.

While other nations purged Ericsson from their networks, Telstra welcomed them in.

Government bureaucrats turned a blind eye. Appeals were blocked. Evidence ignored.

This wasn’t incompetence. It was treachery.

And the cost? Justice denied. Voices erased. Corruption thriving.

This is not just a story. It’s a warning.

Jefferson’s words were not prophecy—they were a blueprint for vigilance. And yet, in the 21st century, we’ve watched as global corporations like Ericsson have infiltrated the very institutions meant to regulate them. Between 2000 and 2016, Ericsson orchestrated a systematic and calculated campaign of bribery and corruption, culminating in a $1.4 billion settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice.

The acquisition of Lane by Ericsson, along with the dealings surrounding the COT Cases, was nothing short of a calculated conspiracy against Australia’s democratic system of justice. This insidious operation has gone largely unacknowledged, revealing a disturbing truth.

The corruption exposed by absentjustice.com is not merely partisan; it reflects a deep-seated, systemic rot that permeates the USA and extends globally. Thomas Jefferson himself would have recognised this treachery. Mighty corporations, like Ericsson, have become predators, systematically devouring the world's integrity.

Ericsson’s ruthless infiltration of Australia's arbitration system is undeniable and raises alarming questions. Why has this company evaded accountability for its questionable actions during the Casualties of Telstra (COT for short) arbitrations? This situation is not just a political issue; it demands urgent action that cuts through the fog of party lines and unearths the treacherous conduct at play.

During my arbitration, Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd was officially appointed as the technical consultant to the arbitrator. Lane had access to sensitive materials, including evidence implicating Ericsson-manufactured telephone exchange equipment—the very hardware that plagued my business and those of other COT claimants.

Yet, in a move that reeks of collusion, Ericsson callously and immorally acquired Lane for an undisclosed sum while confidentiality agreements still bound them. This acquisition occurred during the arbitration period, effectively transferring privileged evidence into the hands of the very company under scrutiny. While reading this section of my story, don't forget what you have already read in 2 Organised Crime and Corruption - Absent Justice

Hovering your cursor or mouse over the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp image below will lead you to a document dated March 1994, referenced as AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings. This document confirms that government public servants investigating my ongoing telephone issues supported my claims against Telstra, particularly between Points 2 and 212. It is evident that if the arbitrator had been presented with AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, he would have awarded me a significantly higher amount for my financial losses than he ultimately did.

He may have spun a web of deception to Laurie James, President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, on 17 February 1996, regarding his collusion with David Read from Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd. These technical consultants were supposedly brought in to assist DMR Group Canada in evaluating the faults within the AXE Portland telephone exchange—an exchange crucial to my business operations at Cape Bridgewater.

COT Case Strategy

Stop the COT Cases at all costs

Mr White "In the first induction - and I was one of the early ones, and probably the earliest in the Freehill's (Telstra’s Lawyers) area - there were five complaints. They were Garms, Gill and Smith, and Dawson and Schorer. My induction briefing was that we - we being Telecom - had to stop these people to stop the floodgates being opened."

Senator O’Chee then asked Mr White - "What, stop them reasonably or stop them at all costs - or what?"

Mr White responded by saying - "The words used to me in the early days were we had to stop these people at all costs".

Senator Schacht also asked Mr White - "Can you tell me who, at the induction briefing, said 'stopped at all costs" .

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble, Peter Riddle".

Senator Schacht - "Who".

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble and a subordinate of his, Peter Ridlle. That was the induction process-" .

From Mr White's statement, it is clear that he identified me as one of the five COT claimants that Telstra had singled out to be "stopped at all costs" from proving their case against Telstra. One of the named Peter's in this Senate Hansard who had advised Mr White we five COT Cases had to stopped at all costs is the same Peter Gamble who swore under oath, in his witness statement to the arbitrator, that the testing at my business premises had met all of AUSTEL’s specifications when it is clear from Telstra's Falsified SVT Report that the arbitration Service Verification Testing (SVT testing) conducted by this Peter did not meet all of the governments mandatory specifications.

Also, in the above Senate Hansard on 24 June 1997 (refer to pages 76 and 77 - Senate - Parliament of Australia Senator Kim Carr states to Telstra’s main arbitration defence Counsel (also a TIO Council Member) Re: Alan Smith:

Senator CARR – “In terms of the cases outstanding, do you still treat people the way that Mr Smith appears to have been treated? Mr Smith claims that, amongst documents returned to him after an FOI request, a discovery was a newspaper clipping reporting upon prosecution in the local magistrate’s court against him for assault. I just wonder what relevance that has. He makes the claim that a newspaper clipping relating to events in the Portland magistrate’s court was part of your files on him”. …

Senator SHACHT – “It does seem odd if someone is collecting files. … It seems that someone thinks that is a useful thing to keep in a file that maybe at some stage can be used against him”.

Senator CARR – “Mr Ward, we have been through this before in regard to the intelligence networks that Telstra has established. Do you use your internal intelligence networks in these CoT cases?”

The most alarming aspect of Telstra's intelligence networks in Australia is who within the Telstra Corporation has the necessary expertise, i.e., government clearance, to filter the raw information collected before it is impartially catalogued for future use? How much confidential information concerning the telephone conversations I had with the former Prime Minister of Australia in April 1993 and again in April 1994, regarding Telstra officials, holds my Red Communist China episode, which I discussed with Fraser?

More importantly, when Telstra was fully privatised in 2005, which organisation in Australia was given the charter to archive this sensitive material that Telstra had been collecting about its customers for decades?

PLEASE NOTE:

At the time of my altercation referred to in the above on 24 June 1997, Senate - Parliament of Australia, my bankers had already lost patience and sent the Sheriff to ensure I stayed on my knees. I threw no punches during this altercation with the Sheriff, who was about to remove catering equipment from my property, which I needed to keep trading. I actually placed a wrestling hold, ‘Full Nelson’, on this man and walked him out of my office. All charges were dropped by the Magistrate's Court of Appeal when it became obvious that this story had two sides

As shown in government records, the government assured the COT Cases (see point 40 Prologue Evidence File No/2), Freehill Holingdale & Page would have no further involvement in the COT issues the same legal firm which when they provided Ian Joblin, clinical psychologist's witness statement to the arbitrator, it was only signed by Maurice Wayne Condon, of Freehill's. It bore no signature of the psychologist.

During my arbitration proceedings in 1994, I disclosed to Mr Joblin that Telstra had been monitoring my daily activities since 1992. Furthermore, I presented Freedom of Information (FOI) documents indicating that Telstra had redacted key portions of the recorded conversations regarding my case. This disclosure visibly troubled Mr Joblin, who realised he had been misled by Telstra's legal representatives, specifically those from Freehill Hollingdale & Page. I was able to provide compelling evidence that this law firm had supplied Mr Joblin with a misleading report concerning my telecommunications issues before our interview. Mr Joblin acknowledged that his findings would address these troubling concerns in light of this information. However, it is crucial to note that, despite the gravity of the situation, no adverse findings were made against either Telstra or Freehill Hollingdale & Page.

Mr Joblin insisted that he would note in his report to Freehill Hollingdale & Page the inappropriate nature of Telstra's treatment of me. He emphasised that their methods of assistance warranted careful review. Nevertheless, it is essential to highlight that no adverse findings were documented against Telstra or Freehill Hollingdale & Page.

A critical question remains: Did Maurice Wayne Condon intentionally remove or alter any references in Ian Joblin's initial assessment regarding my mental soundness?

1. Any explanation for the apparent discrepancy in the attestation of the witness statement of Ian Joblin ?2. Were there any changes made to the Joblin statement originally sent to Dr Hughes compared to the signed statement?

AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, dated 4 March 1994, confirmed that my claims against Telstra were validated (see points 2 to 212 in that report). Unfortunately, I did not receive a copy of these findings until November 23, 2007, 12 years after the termination of my arbitration process. Moreover, the government officials had already validated my claims as early as March 4, 1994, six weeks before April 21, 1994, when I signed the arbitration agreement.

But despite that, I was still required to pay over $300,000 in arbitration fees to prove something the government had already established in my case, that Telstra was still not meeting their General Carriers licensing conditions in regard to my service lines at the time the arbitrator Dr Gordon Hughes stopulated in his award findings that Telstra had met those continues after July 1994 as point 2.23 (h) in his award states.

In straightforward terms, AUSTEL (now known as ACMA) failed in its legal obligations to me by not directing the arbitrator to modify his decision until Telstra could demonstrate compliance with its licensing conditions. The attached evidence, Chapter 4: The New Owners Tell Their Story, shows that Telstra was still not meeting those licensing conditions as recently as November 2006, nine years after the arbitrator prematurely issued his findings.

What is important to add here is that the Candadian Prinipal technical advisor, Paul Howell, in his 30 April 1995 formal report, advised Dr Gordon Hughes (the arbitrator) that:

“One issue in the Cape Bridgewater case remains open, and we shall attempt to resolve it in the next few weeks, namely Mr Smith’s complaints about billing problems.

“Otherwise, the Technician Report on Cape Bridgewater is complete.” ( Open Letter File No/47-A to 47-D)

and

“Continued reports of 008 faults up to the present. As the level of disruption to overall CBHC service is not clear, and fault causes have not been diagnosed, a reasonable expectation that these faults would remain ‘open’,” (Exhibit 45-c -File No/45-A)

As of 2026, Dr Hughes has not provided any explanations regarding why he and his technical consultants failed to diagnose the issue. Additionally, he has not addressed the issue of my two service lines being locked, which was causing my ongoing billing issues.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

The Canadian Government's stance on the Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) Cape Bridgewater telephone exchange report reveals a troubling scenario: in Australia, no entity—be it the government, legal professionals, or those who oversaw the arbitration process—made any effort to uncover the truth. A Canadian technical consultant was dispatched to Australia, ostensibly to address critical concerns; still, in reality, this was merely a façade to conceal the findings of the principal technical consultant, Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd (Australia).

Lane was entrusted with the pivotal task of investigating severe deficiencies in the Ericsson telephone exchanges, which not only affected the COT cases but also underpinned telecommunications across much of Australia. In the middle of 1995, amid escalating tensions surrounding telecommunications quality, arbitration administrators appointed Lane under the directive of DMR Group Canada Inc. This group had been specifically chosen to scrutinise my allegations that Telstra had manipulated the Cape Bridgewater testing processes attributed to Bell Canada International.

Such manipulation severely compromised my ability to demonstrate that my telephone service remained subpar, even as Telstra continued to use the notoriously faulty AXE Ericsson telephone equipment. Lane’s investigation unfolded just before the Canadian team arrived, leading to an astounding turn of events when Ericsson later acquired Lane (purchasing it for an undisclosed sum) during the turbulent COT arbitration period.

Unbeknownst to the Canadian authorities at the time, they believed that if my claims against Bell Canada International were substantiated, it would not only reveal significant flaws within their system but also damage the reputations of other respected Canadian telecommunications companies known for their technological expertise.

As this situation unfolded, Canada’s integrity was about to undergo another major test—one that would connect my personal experience to their broader stance in a distant part of the world. DMR Group Canada Inc., which was meant to be monitoring Lane, did provide me with a signature on their combined findings regarding my DMR and Lane report from April 30, 1995, but this was not received until August 1997—eighteen months after my arbitration with Lane had concluded, and without having signed it off.

Corruption reigned as Lane was swiftly acquired by Ericsson during the COT Case arbitrations, even while it was investigating the flawed Ericsson telephone equipment. The Australian Government, complicit in this treachery, permitted the foreign giant to buy the very witness that should have exposed their wrongdoing. Lane, which had the potential to deliver damning evidence against the faulty Ericsson AXE testing procedures at Portland and Cape Bridgewater, instead made no findings regarding the ongoing telephone problems experienced with the Ericsson AXE equipment installed in the exchanges at Portland and Cape Bridgewater.

How could such blatant and unethical manipulation occur in a supposedly impartial system? Just weeks earlier, on March 9, 1995, Warwick Smith had provided written assurances that Lane would support only DMR Canada, noting that DMR was the principal investigator overseeing the situation. This was particularly concerning because, before Smith’s assurance, the COT cases had explicitly rejected Lane’s involvement due to their ties as former Telstra officials, raising significant questions about their objectivity.

However, what the Australian Government was unaware of was that Australia’s first appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), Warwick Smith—also the first appointed arbitration administrator—was, six months before the first four government‑endorsed arbitrations commenced (my arbitration being one of those four), secretly assisting the government‑owned Telstra Corporation to undermine those arbitrations. He did this by providing in‑house, Parliament House–confidential COT Cases information, which not only assisted Telstra in defeating the COT Cases but also helped Telstra conceal the true extent of the defectiveness of its Ericsson AXE telephone equipment.

• major international contracts could have been jeopardised• government infrastructure plans would have been called into question• Telstra’s credibility as a national carrier would have been damaged• Ericsson’s global reputation would have taken a direct hit

• other customers• regulators• international carriers• courts• procurement bodies

• global telecommunications competition• billion‑dollar equipment contracts• government credibility• international corporate reputations• and the integrity of Australia’s first industry‑wide arbitration process

TIO Evidence File No 3-A is an internal Telstra email (FOI folio A05993) dated 10 November 1993 from Chris Vonwiller to Telstra’s corporate secretary Jim Holmes, CEO Frank Blount, group general manager of commercial Ian Campbell and other important members of the then-government-owned corporation. The subject is Warwick Smith – COT cases, and it is marked as CONFIDENTIAL:

Exhibit TIO Evidence File No 3-A confirms that two weeks before the TIO was officially appointed as the administrator of the Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP), which became the Fast-Track Arbitration Procedure (FTAP), he provided the soon-to-be defendants (Telstra) with privileged, government party room information about the COT cases. Thus, the TIO breached his duty of care to the COT claimants and compromised his future position as the official independent administrator of the process.

It is highly likely the advice the TIO gave to Telstra’s senior executive, in confidence (that Senator Ron Boswell’s National Party Room was not keen on holding a Senate enquiry), later prompted Telstra to have the FTSP non-legalistic commercial assessment process turned into Telstra’s preferred legalistic arbitration procedure, because they now had inside government privileged information: there was no longer a significant threat of a Senate enquiry.

To further give Telstra a winning edge in the COT Cases, Warwick Smith and the arbitrator, Dr Gordon Hughes, allowed Telstra to draft its own arbitration agreement rather than an independent agreement designed to give each side an equal chance of success.

In my case, even though Dr Hughes condemned the arbitration agreement he had just used in my 11 May 1995 arbitration—writing to Warwick Smith on 12 May 1995 to show him where the arbitration rules had disadvantaged me—he still covertly used that same agreement in my arbitration. I believe this is what concerned the Canadian Government, and why they attempted to assist me in this matter.

In assessing my case, Lane investigated and commented on only 23 of the more than 200 complaints I had submitted for arbitration. Though DMR Canada was obligated to visit my business and the two telephone exchanges with which I was connected, they failed to conduct the necessary tests on my three telephone lines or the Ericsson equipment at these exchanges, even though this equipment was under scrutiny, the critical reason the COT cases were being arbitrated.

• The Ericsson case highlights how corporate decisions—such as acquiring compliant consultancy firms—can be influenced by broader geopolitical and legal pressures.• It also underscores the risks of opaque alliances and the importance of transparency, especially when operating in conflict zones or under authoritarian regimes.

None of the COT Cases was granted leave to appeal their arbitration awards—even though it is now clear that the purchase of Lane by Ericsson must have been in motion months before the arbitrations concluded. It is crucial to highlight the bribery and corruption issues raised by the US Department of Justice against Ericsson of Sweden, as reported in the Australian media on 19 December 2019.

One of Telstra's key partners in the building out of their 5G network in Australia is set to fork out over $1.4 billion after the US Department of Justice accused them of bribery and corruption on a massive scale and over a long period of time.

Sweden's telecoms giant Ericsson has agreed to pay more than $1.4 billion following an extensive investigation which saw the Telstra-linked Company 'admitting to a years-long campaign of corruption in five countries to solidify its grip on telecommunications business. (https://www.channelnews.com.au/key-telstra-5g-partner-admits-to-bribery-corruption/)

To this day, I have never received the critical reports on Ericsson’s exchange equipment—painstakingly compiled by my trusted technical consultant, George Close. These documents were the backbone of my case. Their disappearance is a blatant violation of the arbitration rules, which require all submitted materials to be returned to the claimant within six weeks of the arbitrator’s award.

• Ericsson paid $1.06 billion in penalties:• $520 million to the DOJ• $540 million to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission• In 2023, Ericsson paid an additional $206 million for breaching its deferred prosecution agreement by withholding misconduct details, including alleged dealings with ISIS in Iraq.

• In 1993, a Telstra briefcase left at Cape Bridgewater revealed internal knowledge of Ericsson faults dating back to 1988.• AUSTEL (now ACMA) condemned Telstra’s testing as grossly deficient in 1994, but these findings were withheld from claimants until years later.• Ericsson acquired Lane Telecommunications, the technical consultant to the arbitrator, during the arbitration—raising serious conflict of interest concerns.

• The arbitrator did not halt proceedings.• COT claimants were not allowed to amend their claims.• Telstra denied equipment faults under oath—reportedly over 30 times.

• Senator Richard Alston raised concerns in Parliament in 1994, citing the severity of Ericsson’s faults.• The Hon. David Hawker MP, Speaker of the House, supported efforts to resolve the issues in his Wannon electorate.• Internal Telstra emails and Senate Hansard entries reveal pressure to suppress COT claims and protect Telstra’s privatization interests.

• Why was Ericsson allowed to acquire Lane Telecommunications mid-arbitration?• Who in government knew about the equipment faults and failed to act?• Why were arbitration findings based on suppressed or falsified evidence?• What role did political deals play in shielding Ericsson and Telstra from accountability?

I had never spoken to Mr Howell before, but he stated that my arbitration was nothing but a criminal cover-up. He expressed concern about how the proceedings were conducted while serving as a technical adviser. His apology, along with his notes, was included in a statutory declaration submitted to The Hon. Michael Lee MP, the Minister for Communications. Unfortunately, I have not received a response from the Minister.

When I informed four different representatives from AUSTEL (now known as ACMA) about Mr Howell's alarm regarding the Bell Canada test calls used in my arbitration by Telstra and Dr Hughes, which they claimed demonstrated that my business was not experiencing additional telephone issues, all four representatives refused to get involved.

Had someone listened to Paul Howell, who was specifically brought in from Canada to investigate my claims that the Ericsson AXE telephone exchange serving my business was fundamentally flawed, the 13,590 test calls—if generated—would have proved just how unreliable the Ericsson equipment was. Unfortunately, no one took action to reopen the arbitration process for me.

During my arbitration, I discovered that the arbitration technical consultants Lane, appointed to assist Paul Howell, had conducted all the groundwork for my Ericsson claim documents. This included drafting the evaluation dated April 6, 1995, which served as the basis for the formal, final technical report used by Dr Hughes to determine my claim. Lane did not make any findings in the report provided to Paul Howell, who then explained that this was why he refused to sign his report dated April 30, 1995. Dr Hughes had ordered this report under the arbitration agreement, and I was required to respond to it, even though it had not been signed off as complete.

After my complaints were investigated by Laurie James, President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, Lane was subsequently acquired by Ericsson for an undisclosed amount. At that time, they were still evaluating several other Claims of Time (COT) cases against Ericsson. Additionally, Lane took with them all of my technical Ericsson data and personal diary logbooks, putting them in a similar situation to the other COT cases, despite the Confidentiality Agreement prohibiting such influence in our arbitrations. Ericsson already had a bad reputation, and the following link concerning alleged terrorist ties to Iraq and ISIS only compounded the issue

Two of the most disastrous deals ever struck by any Australian Coalition Government

The Deal

By 2026, it has become chillingly clear that the treacherous deals struck for 14 Australian small business owners in 2006 have cast a sinister shadow over the Coalition government that orchestrated these agreements, shamelessly manoeuvring to resolve their Telstra arbitration claims dating back to 1994. This disturbing pattern can be traced back to the mid-1960s, when the government made a morally reprehensible decision to supply communist China with Australian wheat. Alarmingly, much of this wheat was insidiously funnelled into North Vietnam, directly supporting the Viet Cong forces responsible for the deaths and injuries of countless brave Australian, New Zealand, and U.S. troops entangled in the brutal jungles of that war-torn country → Chapter 7- Vietnam-Viet-Cong-2. This reckless trade not only betrayed our soldiers but also dragged Australia into a dark moral abyss, leaving a stain of corruption and betrayal that we have yet to escape.

Deleted Without Being Read: The DCITA Cover-Up

From the beginning, the DCITA assessment was cloaked in secrecy. There was no transparency, no accountability. Then, in August 2006, the process was abruptly shut down—without explanation. Ronda Fienberg, my dedicated and loyal editor, received confirmation on 1st February 2008 that her 23 Apr 2006 email, sent that day, had been deleted without being opened. But what’s truly chilling is that two critical items which formed my 2006 submission to the government were never read. They were deleted on 1 February 2008, more than 18 months after they were sent.

Here’s the proof → that a part of my DCITA submission, this one dated 23 April 2006, was deleted on 1 Feb 2008 without being valued (assessed for its relevance) →

MESSAGES RECEIVED 1st February 2008, on behalf of Alan Smith:

Your message

To: Coonan, Helen (Senator) Cc:Lever, David; Smith, Alan Subject: ATTENTION MR JEREMY FIELDS, ASSISTANT ADVISOR Sent: Sun, 23 Apr 2006 17:31:41 +1100 was deleted without being read on Fri, 1 Feb 2008 16:56:36 +1100

ATTACHMENT:

Final-Recipient: RFC822; Senator.Coonan@aph.gov.au

Disposition: automatic-action/MDN-sent-automatically; deletedX-MSExch-Correlation-Key: sdD1TSUHx0CoTD0Qm4wBVw==

Here’s the proof that a part of my DCITA submission, this one dated 25 July 2006, was deleted on 1 Feb 2008 without being valued (assessed for its relevance) →

Original-Message-ID: 001601c6669f$95736a00$2ad0efdc@Office

Your message To: Coonan, Helen (Senator) Cc: Smith, Alan Subject: Alan Smith, unresolved Telstra matters Sent:Tue, 25 Jul 2006 00:00:42 +1100 was deleted without being read on Fri, 1 Feb 2008 16:56:23 +1100ATTACHMENT:Final-Recipient: RFC822; Senator.Coonan@aph.gov.au Disposition: automatic-action/MDN-sent-automatically; deleted X-MSExch-Correlation-Key: bNlMYfUKcUGqvIXiYQZULA==

Original-Message-ID: 003a01c6af21$2b7ece30$2ad0efdc@Office

It is abundantly clear that my 2006 DCITA assessment process for secretarial fees was a staggering $16,000, while my technical expenses to George Close ballooned to $8,000. To add to this, my two flights to the heart of political machinations at Parliament House in Canberra, one in March 2006 and the other in September 2006, racked up costs nearing $3,000, including accommodation. The insidious truth emerged: the government had no intention of valuing my claim meaningfully.

“Hundreds of federal public servants were sacked, demoted or fined in the past year for serious misconduct. Investigations into more than 1000 bureaucrats uncovered bad behaviour such as theft, identity fraud, prying into file, leaking secrets. About 50 were found to have made improper use of inside information or their power and authority for the benefit of themselves, family and friends“

Therefore, I have relied on page 3 of the Herald Sun (22 December 2008), published under the blunt and telling headline “Bad Bureaucrats,” because it is short‑worded, direct, and impossible to misinterpret. It stands as further proof that Australia’s government public servants have, at times, behaved as a law unto themselves and must be held accountable for their misconduct. Were some of these "Bad Bueaucrats" chosen by the Liberal Coalition Government to assess the COT Cases 205/2006 DCITA claims?

"Beware The Pen Pusher Power - Bureaucrats need to take orders and not take charge”, which noted:“Now that the Prime Minister is considering a wider public service reshuffle in the wake of the foreign affairs department's head, Finances Adamson, becoming the next governor of South Australia, it's time to scrutinise the faceless bureaucrats who are often more powerful in practice than the elected politicians."

"Outside of the Canberra bubble, almost no one knows their names. But take it from me, these people matter."

"When ministers turn over with bewildering rapidity, or are not ‘take charge’ types, department secretaries, and the deputy secretaries below them, can easily become the de facto government of our country."

"Since the start of the 2013, across Labor and now Liberal governments, we’ve had five prime ministers, five treasurers, five attorneys-general, seven defence ministers, six education ministers, four health ministers and six trade Ministers.”

This article was quite alarming. It was disturbing because Peta Credlin, someone with deep knowledge of Parliament House in Canberra, has accurately addressed the issue at hand. I not only relate to the information she presents, but I can also connect it to the many bureaucrats and politicians I have encountered since exposing what I did about the China wheat deal back in 1967, and the corrupted arbitration processes of 1994 to 1998. These government stuff-ups and cover-ups have cost lives.

And what about the Liberal Coalition’s disastrous Robodebt saga, which cost them many votes in the 2023 election—suicides, the extortion of money from vulnerable Australians, refer to Royal Commission into the Robodebt Scheme, which was "scathing" of Campbell, finding she had intentionally misled cabinet about the scheme, and took steps to prevent the unlawfulness of Robodebt being uncovered. The same pattern of coercion we faced when we COT Cases were forced to pay for our 2026 DCITA assessment process, even as the Liberal Coalition government was destroying the evidence supporting our claims before it was ever assessed.

The information that was deleted without being opened exposed the following:

• Conflicts of interest at the highest levels• Public officials compromised by their proximity to Telstra• Decisions influenced improperly, and in some cases unlawfully• Threats and pressure used to force citizens into a defective arbitration process• Favouritism and insider advantage that shaped outcomes long before evidence was even heard

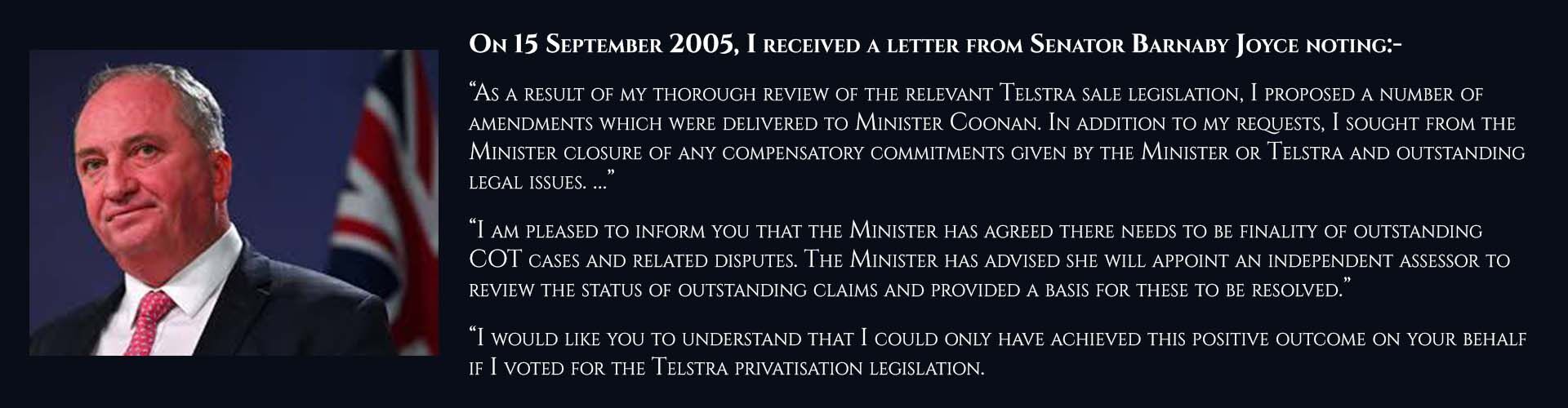

On March 3, 2006, Senator Barnaby Joyce penned a letter to Ann Garms, the spokesperson for my claim and Sandra Wolf’s claim, during the murky government assessment process. Initially, Senator Joyce had been given the dubious assurance that the assessment would be conducted independently and free from government manipulation. However, in a blatant display of allegiance, he agreed to cast his critical vote in the Senate in favour of the sale of Telstra.

“I met with Senator Coonan yesterday morning to discuss the matter of the agreed Independent Assessment of your claims. …

“From my understanding of the CoTs evidence, the Department and the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman have not acted in the best interests of the CoTs. It could be said they have not investigated valid submissions concerning the misconduct of Telstra and the evidence the dispute resolution processes you have all been subjected to over the last decade were flawed. …

“At the meeting yesterday I argued your cases strongly and informed the Minister that justice delayed is justice denied.”

Despite assurances to Senator Joyce that the assessment process would remain independent of government influence, the government allowed Telstra to evaluate my claim instead of appointing an independent commercial assessor as originally promised. This decision is particularly troubling, given that my submissions, which remain relevant in 2026, clearly highlight Telstra’s concerning conduct. Multiple Senators, the Commonwealth Ombudsman, and the Australian Federal Police (AFP) have criticised Telstra, various government bureaucrats, and its regulatory bodies for significant misconduct during and for years after the COT arbitrations.

It is crucial to bring to light the disturbing truth behind the hundreds of thousands of documents that were deliberately withheld during the COT Cases arbitrations. These documents are entangled with the dark legacy of Senator Bob Collins, a notorious paedophile who brazenly abused children in his Parliament House Canberra office while he held the influential position of minister for communications—responsible for overseeing the investigation of the COT Cases claims. This sinister connection mirrors the recent, scandalous releases of files in the Jeffrey Epstein paedophile case, which were heavily redacted and, in many instances, rendered virtually unreadable. It’s a chilling reflection of the lengths to which those in power will go to conceal their heinous deeds.

Furthermore, it is essential to consider Wayne Goss's role, as referenced in Ann Garm's letter regarding the COT Cases. As a former Premier of Queensland, he undoubtedly possessed crucial insights into the insidious gaslighting techniques employed to sabotage our health and well-being. This manipulation serves not only to discredit our experiences but also to perpetuate a cycle of deceit and corruption that remains disturbingly prevalent. The labyrinth of power, secrecy, and exploitation runs deep, and it’s time to expose these corrupt practices for what they truly are.

Don't forget to hover your mouse over the following images as you scroll down the homepage.

23 June 2015: Had the arbitrator appointed to assess my arbitration claims correctly investigated all of my submitted evidence, it would have validated my claim as an ongoing problem, not a past problem, as his final award shows. It is clear from the following link—Unions raise doubts over Telstra's copper network; workers using ...—that when read in conjunction with Can We Fix The Can, released in March 1994, these copper‑wire network faults had existed for more than 24 years.9 November 2017: Sadly, many Australians in rural Australia can only access a second‑rate NBN. This didn’t have to be the case. Had the Australian government ensured that the arbitration process it endorsed to investigate the COT cases’ claims of ongoing telephone problems was conducted transparently, it could have used our evidence to begin fixing the problems we uncovered in 1993–94. This news article— https://theconversation.com/the-accc-investigation-into-the-nbn-will-be-useful-but-its-too-little-too-late-87095,—again shows that the COT Cases’ claims of an ailing copper‑wire network were more than valid.28 April 2018: This ABC news article regarding the NBN—NBN boss blames Government's reliance on copper for slow ...—needs to be read in conjunction with my own story from 1988 through to 2025, because had the arbitration lies told under oath by so many Telstra employees not occurred, the government would have been in a far better position to evaluate just how bad the copper‑wire Customer Access Network (CAN) was only seven years ago.

Point 115 –“Some problems with incorrectly coded data seem to have existed for a considerable period of time. In July 1993 Mr Smith reported a problem with payphones dropping out on answer to calls made utilising his 008 number. Telecom diagnosed the problem as being to “Due to incorrect data in AXE 1004, CC-1. Fault repaired by Ballarat OSC 8/7/93, The original deadline for the data to be changed was June 14th 1991. Mr Smith’s complaint led to the identification of a problem which had existed for two years.”

Point 130 – “On April 1993 Mr Smith wrote to AUSTEL and referred to the absent resolution of the Answer NO Voice problem on his service. Mr Smith maintained that it was only his constant complaints that had led Telecom to uncover this condition affecting his service, which he maintained he had been informed was caused by “increased customer traffic through the exchange.” On the evidence available to AUSTEL it appears that it was Mr Smith’s persistence which led to the uncovering and resolving of his problem – to the benefit of all subscribers in his area”.

Point 153 –“A feature of the RCM system is that when a system goes “down” the system is also capable of automatically returning back to service. As quoted above, normally when the system goes “down” an alarm would have been generated at the Portland exchange, alerting local staff to a problem in the network. This would not have occurred in the case of the Cape Bridgewater RCM however, as the alarms had not been programmed. It was some 18 months after the RCM was put into operation that the fact the alarms were not programmed was discovered. In normal circumstances the failure to program the alarms would have been deficient, but in the case of the ongoing complaints from Mr Smith and other subscribers in the area the failure to program these alarms or determine whether they were programmed is almost inconceivable.”Point 209 –"Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp has a history of service difficulties dating back to 1988. Although most of the documentation dates from 1991 it is apparent that the camp has had ongoing service difficulties for the past six years which has impacted on its business operations causing losses and erosion of customer base.”

The Hidden Cost of Cape Bridgewater’s Failing Telephone Lines