WikiLeaks exposing the truth

A young man (a boy) with a Conscience.

Julian Assange provided a vital link for the COT cases, but we did not know this during our arbitrations.

A statutory declaration prepared by Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson) on 7 July 2011 was provided to the Victorian Attorney-General, Hon. Robert Clark. This statutory declaration discusses three young computer hackers who phoned Graham to warn him during the 1994 COT arbitrations. The hackers discovered that Telstra and others associated with our arbitrations acted unlawfully towards the COT group. Graham’s statutory declaration includes the following statements:

“After I signed the arbitration agreement on 21st April 1994 I received a phone call after business hours when I was working back late in the office. This call was to my unpublished direct number.

“The young man on the other end asked for me by name. When I had confirmed I was the named person, he stated that he and his two friends had gained internal access to Telstra’s records, internal emails, memos, faxes, etc. He stated that he did not like what they had uncovered. He suggested that I should talk to Frank Blount directly. He offered to give me his direct lines in the his Melbourne and Sydney offices …

“The caller tried to stress that it was Telstra’s conduct towards me and the other COT members that they were trying to bring to our attention.

“I queried whether he knew that Telstra had a Protective Services department, whose task was to maintain the security of the network. They laughed, and said that yes they did, as they were watching them (Telstra) looking for them (the hackers). …

“After this call, I spoke to Alan Smith about the matter. We agreed that while the offer was tempting we decided we should only obtain our arbitration documents through the designated process agreed to before we signed the agreement.” (See Hacking – Julian Assange File No/3)

On the covering page of a joint 10-page letter dated 11 July 2011 to the Hon Robert McClelland, federal attorney-general and the Hon Robert Clark, Victorian attorney-general, I note:

“In 1994 three young computer hackers telephoned Graham Schorer, the official Spokesperson for the Casualties of Telstra (COT) in relation to their Telstra arbitrations.

- Was Jullian Assange one of these hackers?

- The hackers believed they had found evidence that Telstra was acting illegally.

- In other words, we were fools not to have accepted this arbitration file when it was offered to us by the hackers who conveyed to Graham Schorer a sense of the enormity of the deception and misconduct undertaken by Telstra against the COT Cases.” (AS-CAV Exhibit 790 to 818 Exhibit 817)

I also wrote to Hon. Robert Clark on 20 June 2012 to remind him that his office had already received a statutory declaration from Graham Schorer dated 7 July 2011. I also approached other government authorities and provided the Scandrett & Associates report (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), which leaves no doubt that the hackers were right on target regarding Telstra's electronic surveillance of the COT Cases.

If the hackers were Julian Assange, then Julian Assange carried out a duty to expose what he thought was a crime. Significant law enforcement agencies and the media have been asking the Australian public to disclose incidents which they believe are crimes because doing so is in the public interest. When I exposed similar crimes to the Australian Federal Police - Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1, I was penalised for it when Telstra carried out their threats.

I have long believed that the hackers who infiltrated Telstra's Lonsdale telephone exchange in Melbourne harboured motives that transcended the mere breach of telecommunications infrastructure. This incident, compellingly documented by journalist Andrew Fowler in his piece "The Most Dangerous Man in the World" for ABC, is part of a larger narrative involving ethical misconduct regarding Telstra's treatment of the COT Cases, a group of individuals who claimed significant injustices in their dealings with the telecommunications giant.

I suspect that Julian Assange was intricately involved in this hacking operation, driven not just by a desire to unveil corporate malfeasance but also propelled by the deafening silence from the government, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, and two Australian attorneys who seemed indifferent to the plight of those affected. The hackers reached out to Graham Schorer, the spokesperson for the COT Cases, on two separate occasions. This outreach appears to indicate their intention to share critical information directly related to the injustices encountered by those involved in the COT Cases, highlighting the urgency of their mission.

The Freedom of Information documents bolster the perspective I have obtained, which reveals that Telstra operates a complex and extensive internal surveillance network. Alarmingly, this troubling information was known to Senators Schacht and Carr, refer to pages 76 and 77 - Senate - Parliament of Australia when they interrogated Telstra officials on June 24, 1997, about the excessive scrutiny of my private life and the accidental release of newspaper articles concerning me that bore no relevance to my ongoing Telstra arbitration issues.

Furthermore, it is significant to note that Telstra collected detailed information about individuals I contacted and those who contacted me, occasionally recording unusual locations of these interactions in their files. As the Australian Federal Police (AFP) have stated, it seems evident that Telstra could only have obtained this sensitive information if I was under systematic surveillance, raising serious questions about privacy and ethics.

For example, how did Telstra know in April 1994, shortly after I called former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, that I would travel to Melbourne weeks before my scheduled trip? Who was referred to as "Micky," the local Portland Telstra technician, Gordon Stokes, who seemed to have been providing insider information about my contacts? Moreover, why did the arbitrator fail to question Gordon Stokes regarding his disclosure of my private and business contacts to this "Micky" figure?

Could this be the same electronic surveillance Julian Assange alluded to when he informed Graham Schorer (COT Case spokesperson) that we were under constant monitoring? Furthermore, were my concerns about Communist China part of this sophisticated surveillance operation? It raises a pressing question: Will the government take steps to interrogate Julian Assange about the nature of his communication with Mr Schorer and what he meant when he communicated that "we never had a chance to prove our claims" - or words to that effect? Such inquiries not only delve into the specifics of my case but also touch on broader issues of transparency, accountability, and the potential abuse of power within telecommunications and government agencies.

The complexities of war and government deceit are well documented across various platforms, including media articles and at least one internationally released documentary highlighting Julian Assange's profound aversion to warfare. He has consistently condemned the government's efforts to conceal the brutal realities faced by innocent civilians caught in the deadly crossfire. This sentiment resonates deeply with several Canadian and British seamen, including myself, who stood firmly against our governments’ complicity in such matters.

For instance, there was a pivotal moment when we collectively opposed the government's decision to supply grain to Communist China. We understood that this grain was not simply a trade deal; it was a lifeline that ultimately found its way into the bellies of North Vietnamese soldiers, furthering their capacity to wage war. This moral dilemma stirred strong feelings in us, as we recognized the human cost of our government's actions.

In my discussions with former Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, I pressed him about the rationale behind allowing trade with the enemy. This inquiry led me to wonder whether Julian Assange also sought to unravel these intricate connections, primarily when he intended to provide Graham Schorer with critical documents that might shed light on our arbitration efforts.

Could these documents have fueled Julian Assange’s firm conviction against war, mirroring my own? This deep-seated animosity stems from an awareness of how wars often line the pockets of public officials. Historical examples abound, such as the wheat trades with Communist China in the 1960s and the controversial dealings during the 2000s when Australia maintained business ties with Saddam Hussein amid the Iraq War. This intertwining of profit and conflict drives our disdain for war and its grim consequences.

Threats Made

Threats Carried Out

I faced intimidation from Telstra arbitration officials as a direct consequence of my cooperation with the Australian Federal Police (AFP) regarding their investigations into significant phone and fax hacking incidents. During a meeting with Graham Schorer, spokesperson for the Customers of Telstra (COT) Cases, and Ann Garms, we delved into the troubling discussions the hackers had previously shared with Graham. These discussions centred on the electronic surveillance allegedly conducted by Telstra in relation to the COT Cases.

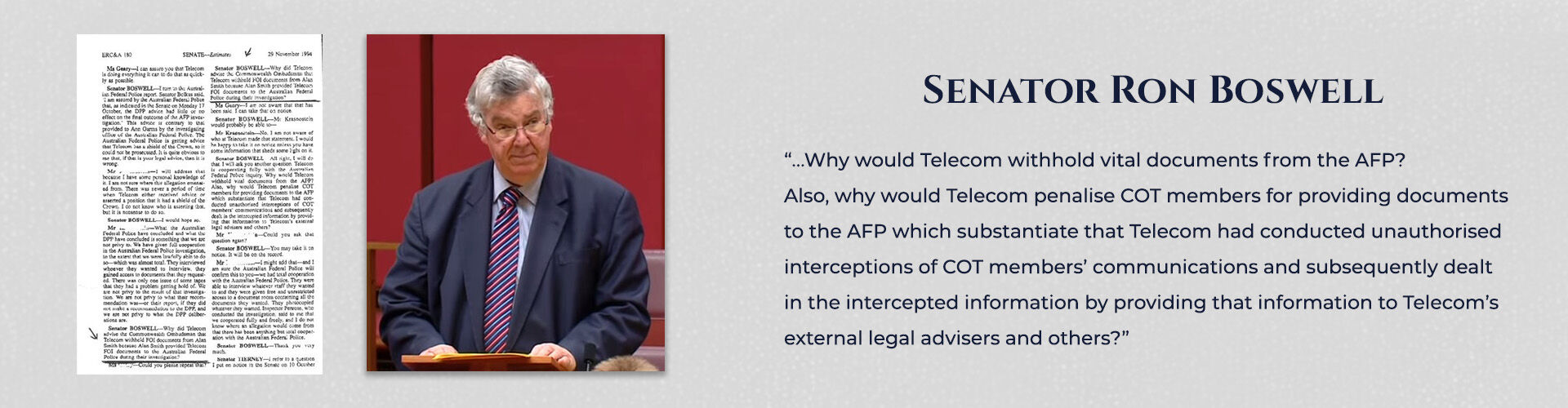

Following a troubling incident in which my faxes did not reach their intended recipients, I alerted Senator Ron Boswell. This was particularly concerning because it echoed the hackers' previous discussions with Graham Schorer. When I brought this matter to Telstra's attention, their response was alarming: they issued threats, warning that if I persisted in raising these issues with the Australian Federal Police, all future Freedom of Information (FOI) requests I submitted would be entirely disregarded. This blatant intimidation tactic went unnoticed and prompted anger from Senator Boswell.

Furthermore, on 29 November 1994, during an official session of the Australian Senate, Senator Ron Boswell posed critical questions to Telstra’s legal directorate regarding these unfolding events and the concerning implications of Telstra's hacking and surveillance practices.

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

The threats I encountered ultimately became a troubling reality. A significant concern regarding the withholding of essential documents is that no individual within the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) office or any government entity has ever conducted a thorough investigation into the damaging effects this withholding had on my overall submission to the arbitrator.

At the time of the arbitration, Telstra was a government-owned corporation, which meant that both the arbitrator and the government should have been particularly vigilant to ensure a fair process. It raises questions about why an Australian citizen who collaborated with the Australian Federal Police (AFP) in its investigation into the unlawful interception of my private telephone conversations faced such severe disadvantages throughout the civil arbitration process.

To illustrate this point, the transcripts from the AFP's second interview with me, conducted on 26 September 1994, explicitly address the threats I experienced. These details can be found on pages 12 and 13 of the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1. The lack of inquiry into these matters not only undermines the integrity of the arbitration process but also highlights a serious failure to protect the rights of an individual who attempted to assist law enforcement in addressing serious misconduct.

Next Page ⟶