Impunity and utter absence of judicial independence

Hiding behind a tainted confidentiality agreement

Please note:

After reading AbsentJustice, most observers would conclude that if I had been allowed to challenge both arbitration resource units, namely Ferrier Hodgson Corporate Advisory (the financial arbitration advisors) and DMR & Lane (the technical arbitration consultants), for negligence and misleading and deceptive conduct during my arbitration, I would have had a reasonable chance of some success.

However, when the arbitrator allowed the removal of clauses 25 and 26 from my arbitration agreement after it had been sent to our lawyers as the final agreement, he effectively stopped me from appealing his award using the misconduct of FHCA and DMR & Lane clauses to sue for wrongdoing. Part 2 - Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct.

On the day we signed the arbitration agreement (Open letter File No 54-B), clause 10.2.2 and the $250,000.00 liability caps in clauses 25 and 26 had been removed, and clause 24 had been modified. We were told there would be NO arbitration if we did not accept these late changes. There was no protection against these threats to sign or else. Being forced to sign a legal document that had been changed to protect Telstra and the consultants that Telstra was paying to assess our arbitration claims was undemocratic, to say the least.

Infringe upon the civil liberties.

Most Disturbing And Unacceptable

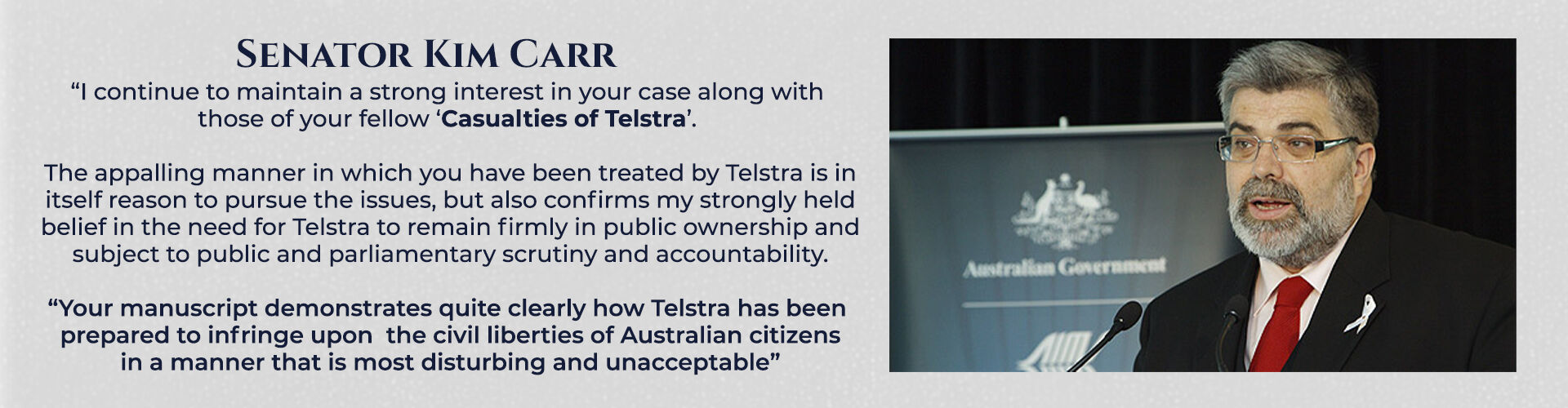

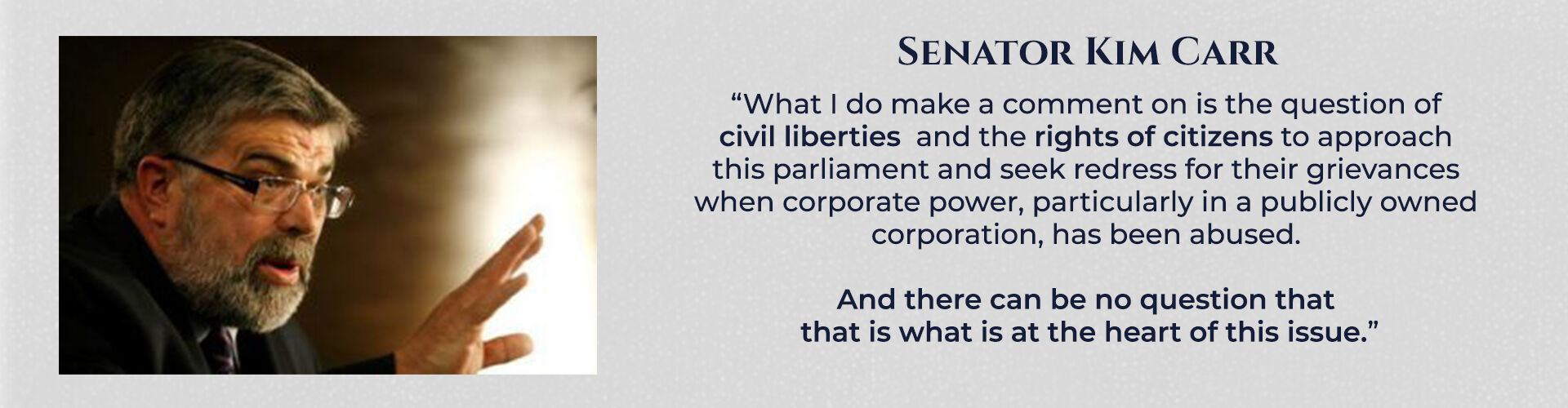

On 27 January 1999, after having also read my first attempt at writing my manuscript absentjustice.com, After reading the first draft of my 280-page manuscript "Absent Justice", Senator Kim Carr wrote:

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

Upon review of the initial twelve pages of my 280-page manuscript, the editor expressed profound astonishment at the depiction of the COT narrative. The manuscript presents a compelling chronicle characterized by treachery, conspiracy, and deception orchestrated by a shrewd and unscrupulous legal practitioner and his arbitration cohorts. Their astute exploitation of a confidentiality agreement, known to have been altered to the detriment of the claimants, effectively obstructed the accessibility of critical evidence to a third party. This strategic manoeuvring, aimed at preventing the potentially devastating use of said evidence in a court action, posed significant repercussions for the government, which held ownership of Telstra during the arbitrations. Dr. Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator, and Warwick Smith, the administrator of the COT arbitrations, have been bestowed with the 'Order of Australia' in recognition of their commendable service to the community..

Welcomed news for five COT's, but not for the remaining sixteen COT cases discarded by the senate

An Injustice to the remaining 16 Australian citizens

Five years too late

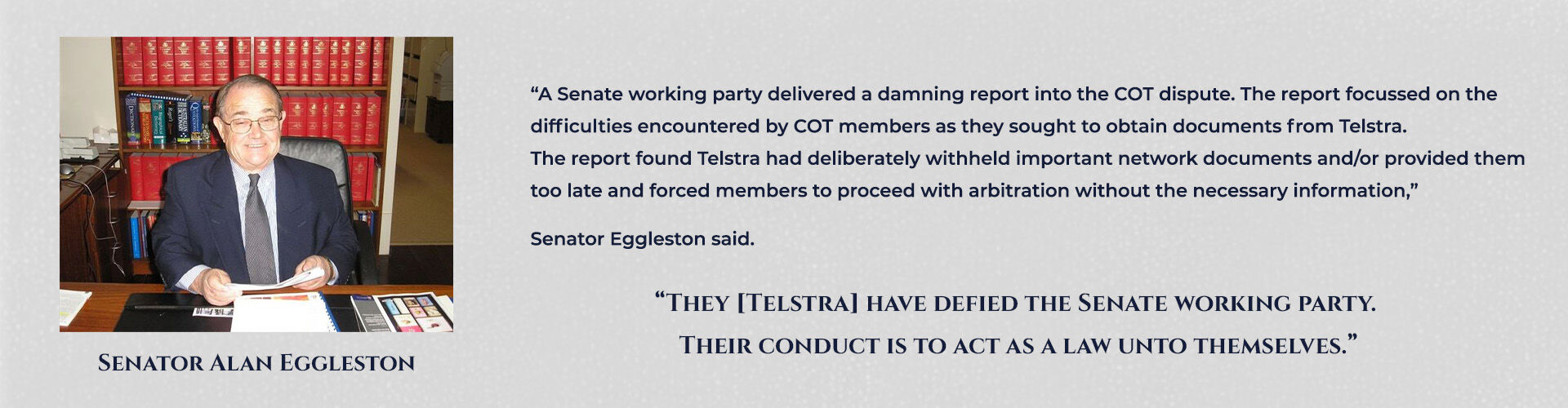

On March 23, 1999, the Australian Financial Review conducted a thorough investigation into the conduct of twenty-one arbitration and mediation processes, including my own, which had been finalized almost five years prior. The findings of their investigation prompted the Senate Estimates Committee to issue a statement.

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They [Telstra] have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

John Rundell, a partner at KPMG (Australian Auditors), knowingly provided inaccurate information to the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman regarding my outstanding 1800 billing claims. It is pertinent to note that in 2024, Mr Rundell is a past treasurer of the IAMA and an established arbitrator practising in Hong Kong and Australia.

File 45-A and 45-E → Open letter File No/45-E.

The IAMA asked for more documents after their third investigation commenced.

When the Australian Institute of Arbitrators and Mediators (IAMA) learned of these injustices, it committed to conducting three separate investigations: first in 1996, then in 2000, and finally in 2009, to examine and reach a conclusion on Chapter 11—The eleventh remedy pursued. Despite my repeated efforts to have the material released, the IAMA has yet to issue any findings or return my 23 bound volumes of evidence.

The deteriorating arbitration system and the flagrant distortion of truth have perverted the course of justice. Selling out the other side of politics— the money grubbers and career dogs, especially politicians— who have compromised their morals and the community's needs in pursuit of illicit personal gain is shaping Australia's legal process, but no one wants to admit it. Instances of foreign bribery, foreign corrupt practices, and international fraud against the government present significant challenges during those arbitrations.

I reiterate that the IAMA Ethics and Professional Affairs Committee has still not brought down a finding, regardless of their advice to me in five emails that they were investigating my matters. One of those five emails, sent at 12:50 pm on 21 October 2009, states:

“Presently, IAMA does not require this further documentation to be sent. However, the investigating persons will be notified of these documents and may request them at a later date.” (Burying The Evidence File 13-B to 13-C)

On 27 November 2009, I sent a further email to the secretary of the IAMA’s CEO, advising him that I could provide solid evidence of the arbitrator’s previous role as Mr Schorer’s legal advisor during a previous Telstra Federal Court matter in which he assisted Telstra to the detriment of his client.

At 2:00 p.m. the same day, I received an email from the IAMA secretary stating, “Your email has been forwarded to the CEO. Regards, Richard.”

Cronyism in the seat of arbitration in Australia has won the day. The economics of corruption is destroying our democratic justice system, yet only a handful of independent politicians are prepared to fight this losing battle in Australia.

Our rights were violated.

We were considered collateral damage - expendable.

The following statement by John Pinnock (the second administrator to the COT arbitrations) on the 26th of September 1997, two years after most of the arbitrations had been concluded, including mine. ( Prologue Evidence File No 22-D) states that:

"...In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures—and I was not a party to that, but I know enough about it to be able to say this—the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act."

“… Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process because it was a process conducted entirely outside of the ambit of the arbitration procedures”.

On the 21st of April 1994, when I affixed my signature to the government-endorsed arbitration agreement, I was unknowingly consenting to a process over which the arbitrator held no control, conducted entirely outside the agreed and accepted ambit of the arbitration procedures. I would not have executed the agreement if I had been privy to this critical information. Additionally, the sentiments expressed by Ann Garms, the late Maureen Gillan, and Graham Schorer, who is currently incapacitated, indicate a shared reluctance to sign the document had they been apprised of the prevailing conditions. The assertion that the Australian government should have promptly invalidated all COT arbitrations upon disclosing pertinent information by John Pinnock, the process administrator, to the Senate on the 26th of September 1997 is solid and valid. The adverse consequences endured over the last thirty years due to the lack of disclosure by Dr Gordon Hughes have been palpable. Had the revelations made by Mr Pinnock been made available during our respective arbitration appeal periods, the potential for successful appeals on at least one aspect of our award would have been significantly augmented.

I made it clear to John Pinnock in late 1995 and again in 1996 that if the $250,000 liability caps in clauses 25 and 26 of my arbitration agreement had not been covertly removed after our lawyers had voted on the unchanged clauses, I would have pursued legal action against the arbitration consultants for negligence. Evidently, the arbitrations had not been conducted within the agreed ambit of the Arbitration Commercial Act, and I needed records from his office to demonstrate who had authorized these wrongful acts. In response to my request, I received the following letter dated 10 January 1996:

“I refer to your letter of 31 December 1996 in which you seek to access to [sic] various correspondence held by the TIO concerning the Fast Track Arbitration Procedure. …

“I do not propose to provide you with copies of any documents held by this office.” (Open Letter File No 57-C)

Assisting an AFP investigation ruined the chance of a transparent finding by the arbitration process.

Blowing the whistle

During the arbitration on March 21, 1995, I and three other COT Cases, namely Ann Garms, Graham Schorer, and a witness from Ballarat (Victoria), were asked to provide evidence of phone and fax interception of our telecommunications during a senate debate in Parliament House Canberra. This evidence was to be used to amend the "Telecommunications (Interception) Amendment Bill 1994".

All four, including me, were found to be suffering from psychological stress disorder (PSD) due to the unlawful monitoring of our private and business telephone conversations by Telstra and its employees without proper authorization from law enforcement agencies.

The witness from Ballarat revealed a troubling account of the adverse effects on his life as a counsellor for gay men and the lives of his clients after discovering that their private discussions about their sexuality were no longer confidential.

Furthermore, Telstra's recording of the name and business of a woman in Portland with whom I was having an affair, coinciding with her business experiencing phone problems, had a profoundly distressing impact on both of us.

I also presented evidence documenting Telstra's recording of my private telephone conversations with the former Prime Minister of Australia Malcolm Fraser, with critical information redacted upon release under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act. Notably, seven senators, including Cooney, Spindler, Ellison, Evans, Vanstone, McKiernan, and O'Chee, were present during the discussion of the “Telecommunications (Interception) Amendment Bill 1994.”

In the Senate Gallery, Superintendent Detective Sergeant Jeff Penrose of the Australian Federal Police was in attendance, having visited my business twice in February and September 1994 to address privacy issues promised to be resolved by the AFP for the four COT Cases. Additionally, Garry Ellicott, an ex-Queensland Detective Sergeant of Police and acclaimed National Crime Investigator, was compensated $57,000.00 from my overall $300,000.00 arbitration cost for elucidating the profound impact of the unauthorized monitoring of my telephone conversations.

The Letter of Claim, submitted to the Arbitrator on June 15, 1994, was slated to be evaluated, and an official written response from the Arbitrator was expected on or before May 11, 1995. It is now July 2024, and despite the government's advisory communication to the Arbitrator on April 13, 1994, emphasizing the necessity for an official written finding on this matter, no decision has yet been rendered.

Why was my discussion information removed from the Malcolm Fraser released to me under FOI?

On 24 March 1994, Telstra's Steve Black informed the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telstra was vetting my FOI documents before they were released in case they were sensitive to Telstra.

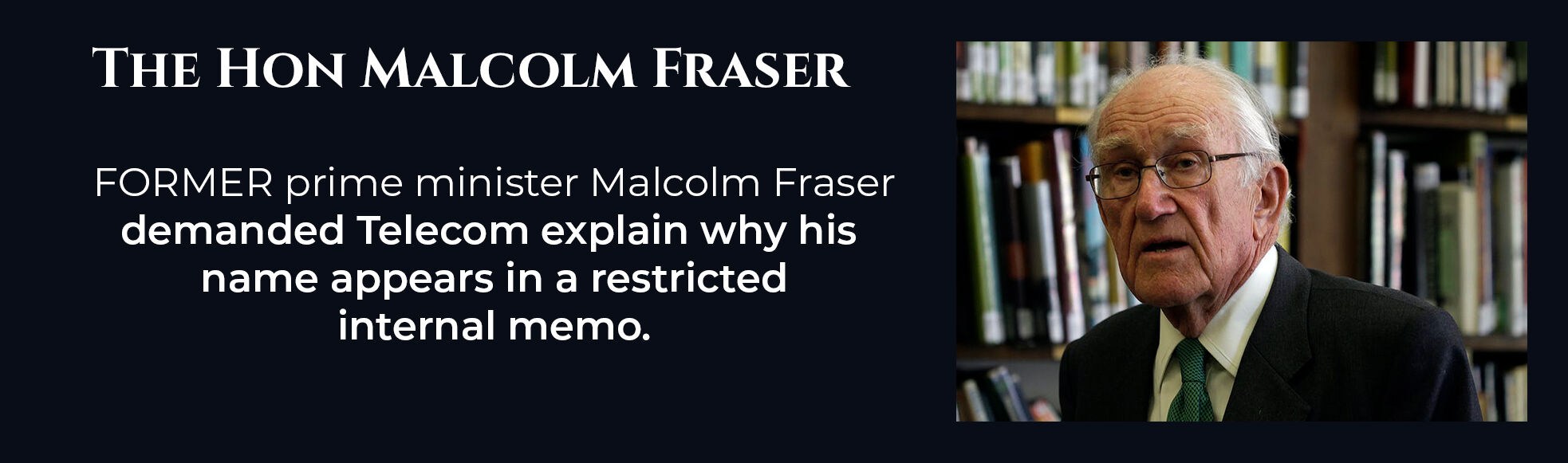

The Hon. Malcolm Fraser, former prime minister of Australia. Mr Fraser reported to the media only what he thought was necessary concerning our telephone conversation, as recorded below:

“FORMER prime minister Malcolm Fraser yesterday demanded Telecom explain why his name appears in a restricted internal memo.

“Mr Fraser’s request follows the release of a damning government report this week which criticised Telecom for recording conversations without customer permission.

“Mr Fraser said Mr Alan Smith, of the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp near Portland, phoned him early last year seeking advice on a long-running dispute with Telecom which Mr Fraser could not help.”

One of my questions raised with Malcolm Fraser was: How could Australia say their selling of wheat to the Republic of China was on humanitarian grounds when the Australian government knew that some of this same wheat was being redeployed to North Vietnam? A country that was killing and maiming as many Australian, New Zealand and USA troops as they could during the Vietnam War?

How was this humanitarian when Australia was contributing to the killing of its own soldiers and the soldiers of its Allies in the Vietnam War?

Could this FOI document be related to my time spent under house arrest in Communist China and what the newspaper journalist told me on 18 September 1967, after I had been forced at gunpoint to state: "I am a US aggressor and a supporter of Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalist Party."

When I told the skipper that writing this statement meant I was signing my death warrant, as Chiang Kai-shek was against Mao Tse Tung, the 'Second Steward' in charge of the ship's correspondence said I was dead if I did not write what these Red Guards were demanding I write → Chapter 7- Vietnam-Vietcong.

The world of political corruption

Graft, malfeasance, and nepotism

The documented evidence indicates that Telstra's CEO and the entire board possessed foreknowledge of millions of dollars being unlawfully withdrawn from government funds. These funds were utilized to exert control over 45 prominent legal firms, thereby obstructing ordinary citizens with claims against Telstra from pursuing legal remedies. This crucial information is publicly available on absentjustice.com, shedding light on pervasive unethical practices and erroneously billed accounts.

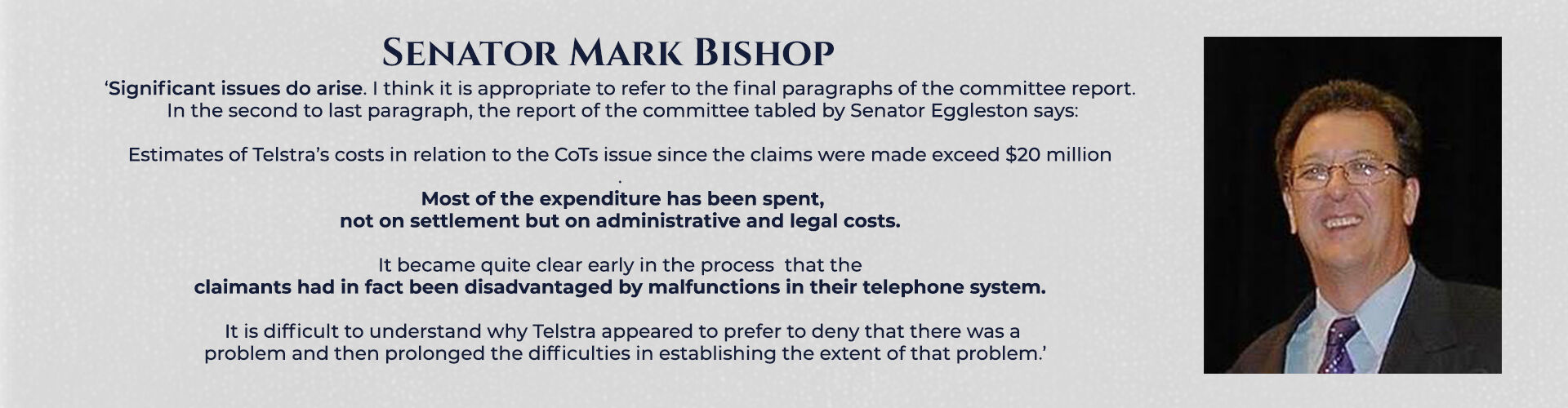

Senator Mark Bishop's denouncement of Telstra's utilization of these 45 prominent legal firms against ordinary Australian citizens and small business operators, who had lodged complaints solely regarding inadequate service, is accessible at parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/displaychamberhansards1999-03-11. His condemnation of this unjust practice underscores the enormity of a government-owned entity, Telstra, employing public funds in opposition to the public interest, constituting an abuse of power. The enduring absence of an investigation into this scandalous matter is noteworthy.

Many of the documents were unreadable.

Telstra was the CAT, and the COT Cases were the mouse.

In the case of Dr Gordon Hughes, the COT arbitrator, it is important that he should have disclosed to the COT Cases and their legal representatives that he operated as an 'ungraded arbitrator' and achieved graded status only after the conclusion of my arbitration. Additionally, he should have informed the COT Cases and their legal representatives that his Sydney-based firm was examining the business affairs of the NSW (Sydney) arm of several Telstra employees. It is also important to note that he should have disclosed that the faxes intended for the COT Cases sent to his Melbourne office were rerouted to his Sydney office outside of standard business hours and during weekends.

When the arbitrator returned the claim documents we had submitted after our arbitrations, we were surprised to discover that many documents and reports were stapled together with unrelated material. Some of the documents even belonged to a different claimant. Despite reporting the issue to the arbitrator and arbitration administrator, John Pinnock, no investigation was conducted as our arbitrations had concluded.

This document mixing-up occurred one month into my arbitration after I received documents and reports from Telstra under Freedom of Information (FOI). The FOI documents did not match the accompanying text and fax-header sheets in several instances. Realizing the seriousness of the issue, I sought intervention from Superintendent Detective Sergeant Jeff Penrose of the Australian Federal Police on May 14, 1994.

He encouraged me to provide evidence of this misconduct to the arbitrator and administrator through a statutory declaration, which I promptly did. Refer to File 76 and 77 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91. Despite providing the arbitrator and the administrator with a copy of Statutory Declaration File 76 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91), which had been given to the Federal Police, neither investigated the FOI document issue.

Concerning document 77 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91, Sue Harlow, Deputy (TIO) Ombudsman, was entrusted with evidence regarding 56 reports that had been tampered with to the extent that they were indecipherable. Notably, the issues relating to tampered arbitration documents from 1994 and 1995 remain uninvestigated as of 2024.

It is deeply concerning that neither Dr. Gordon Hughes (the arbitrator) nor Warwick Smith (the administrator to the arbitrations) saw fit to investigate why Telstra was engaging in such questionable practices when supplying FOI documents. In my case (File 76 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91), I confirmed I found that '56 reports' fax header introduction pages' were stapled with information irrelevant to the attached content. This blatant disregard for proper document handling was unacceptable and warranted immediate attention. It received no response whatsoever.

Heavy-handed tactics

$24 million of moneys being used to crush these people

On March 11, 1999, after Dr Gordon Hughes and Warwick Smith utilized heavy-handed tactics to handle the COT Cases, their arbitrations were concluded, with less than 11 per cent of the claims being met. Senator Kim Carr criticized the handling of the COT arbitrations, as evidenced in the following Hansard link shows:

Addressing the government’s lack of power, he said:

“What I do make a comment on is the question of civil liberties and the rights of citizens to approach this parliament and seek redress for their grievances when corporate power, particularly in a publicly owned corporation, has been abused. And there can be no question that that is what is at the heart of this issue.”

And when addressing Telstra’s conduct, he stated:

“But we also know, in the way in which telephone lines were tapped, in the way in which there have been various abuses of this parliament by Telstra—and misleading and deceptive conduct to this parliament itself, similar to the way they have treated citizens—that there has of course been quite a deliberate campaign within Telstra management to undermine attempts to resolve this question in a reasonable way. We have now seen $24 million of moneys being used to crush these people. It has gone on long enough, and simply we cannot allow it to continue. The attempt made last year, in terms of the annual report, when Telstra erroneously suggested that these matters—the CoT cases—had been settled demonstrates that this process of deceptive conduct has continued for far too long.” (See parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/displaychamberhansards1999-03-11)

Telstra's misuse of public funds, which should have gone to the Australian government instead of paying yearly retainers to 45 leading legal firms, is concerning. Moreover, during the COT arbitrations, they spent an additional $24 million to suppress sixteen Australian small business operators, hindering their efforts to prove events over two decades. This also affected around 120,000 similar COT cases, where individuals were fighting Telstra for a reassessment of their wrongly billed accounts. Senator Kim Carr's statement about the $24 million is deeply troubling for COT cases.

The government did not provide the promised FOI documents.

This website offers in-depth insights into criminal activities involving government agencies and public servants. It is revealed that a Senator responsible for investigating telephone issues affecting citizens had been engaged in raping children in his Parliament House office in Canberra. When the government was asked to release documents related to the pending arbitrations this Senator had facilitated, the government feared that releasing the wrong documents could expose the Senator's criminal conduct. Even further, those documents were not provided. The following letters are documented under reference paedophile activities /government / See File Ann Garms 104 Document, refer (RB.gy/divided).

The sexual abuse and the raping of Australian citizens in Parliament House Canberra during the period of the Casualties of Telstra mediation and then arbitrations is still very much in the public eye in 2024, as the following Kangaroo Court website https://shorturl.at/svwI5 shows.

The sexual abuse and the raping of Australian citizens in Parliament House Canberra during the period of the Casualties of Telstra mediation and then arbitrations is still very much in the public eye in 2024, as the following Kangaroo Court website https://shorturl.at/svwI5 shows.

Subsequently, the arbitrations for the COT cases were compromised. The website provides 1,700 government and arbitration-related exhibits that validate our claims and more, available for free download.

The reprehensible behaviour of a government minister has resulted in the denial of the right to a transparent arbitration process for numerous Australian citizens. While it is regrettable to report this fact, it is imperative to disclose the unethical conduct of this senator due to the far-reaching implications it has caused.

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my illegal phone/fax interception allegations. (Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

The internal government memo dated 25 February 1994 confirms that the Minister for Communications and the Arts had written to advise that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone and fax interception ([document | 742]). It is clear that the Labor Party, in power at the time, was penalizing our arbitration claims, and it is evident that the government was intent on protecting Senator Bob Collins's paedophile activities, regardless of his appalling actions. As COT Cases, we were undoubtedly collateral damage in this situation.

The fax imprint across the top of this letter dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the January 1999 Scandrett & Associates report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations. One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

Telstra is run by 'thugs in suits'

Telstra threats carried out.

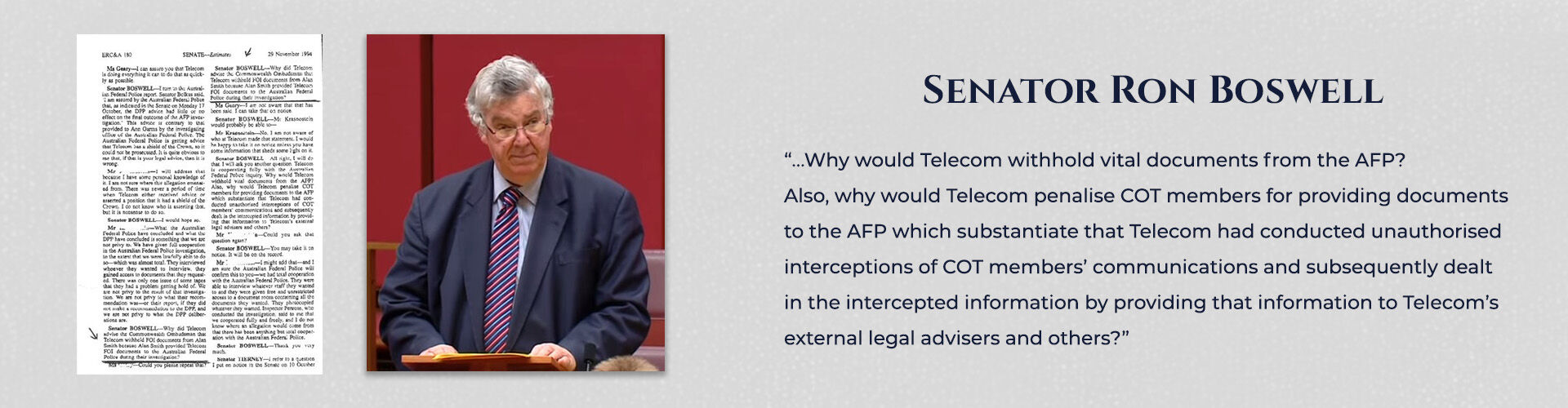

Page 180 ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard dated November 29, 1994, outlines Senator Ron Boswell's inquiry to Telstra's legal directorate concerning withholding my 'Freedom of Information' documents during arbitration. These events stem from my cooperation with the AFP in their investigations into Telstra's interception of my telephone conversations. I was also asked about my knowledge of any paedophile activities by a Senator and the responses, if any, to the false fax header information I uncovered on May 14, 1994. These serious matters remain unresolved and necessitate further investigation. The paedophile activities of Senator Collins should not have empowered Telstra to believe they could escape accountability for their threatening actions of thirty years ago.

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” Senate Evidence File No 31)

Despite my full cooperation with the Australian Federal Police (AFP) in their investigation into the unauthorized interception of telephone conversations and arbitration-related facsimiles, I am still awaiting their conclusions on the initial evidence I provided. The AFP's lack of information adversely affected the transparency of the arbitrator's investigations into the same phone and fax hacking issues. Of concern was the necessity for me to simultaneously provide evidence supporting my claims to the AFP and the arbitrator during the thirteen months of my arbitration.

In simpler terms, when compelled as a citizen to aid both the AFP and the arbitrator, who were independently investigating the same matters, the directive to cooperate with both entities concurrently was issued without due consideration. The fact that there is no finding against Telstra for having made and carried out their threats against me that directly impacted the outcome of the commercial side of my arbitration claims is further testament that arbitration in Australia is not the place to receive justice.

The lack of any ruling against Telstra for their threats, which directly impacted the outcome of my arbitration claims, is compelling evidence that justice cannot be attained through arbitration in Australia.

Question 81 in the following AFP transcripts Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 confirms that the AFP told me that AUSTEL's John MacMahon had supplied the AFP evidence my phones had been bugged over an extended period. Why did the arbitrator not award me in his official findings concerning this evidence after he was supplied with the AFP transcripts, for which the AFP advised me the following:

"... it does identify the fact that, that you were live monitored for a period of time. See we're quite satisfied that, there are other references to it".

What incentive would compel an arbitrator to ignore irrefutable evidence attached here as >Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 <?

And still, at least 41 of my faxes did not reach the arbitrator

On 10 February 1994 AUSTEL wrote to Telstra's Steve Black, who was Telstra's principal Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP defence officer), stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

The NINE TAPES. were the crucial 'nine smoking guns' that would undoubtedly bolster our claims against Telstra. On February 15, 1994, Senator Richard Alston raised the nine audio tapes in the Senate on notice (Main Evidence File No/29 QUESTIONS ON NOTICE). Senators Ron Boswell and Richard Alston expressed concerns about the possibility the paedophile activities in Parliament House Canberra had been recorded on these nine COT Cases-related tapes. This could be the reason we, as COT Cases, were being denied access to these tapes.

On 15 February 1994, in the Senate, Senator Alston asked Telstra:

- Could you guarantee that no Parliamentarians who have had dealings with ‘COT’ members have had their phone conversations bugged or taped by Telstra?

- Who authorised this taping of ‘COT’ members’ phone conversations and how many and which Telstra employees were involved in either making the voice recordings, transcribing the recordings or analysing the tapes?

- On what basis is Telstra denying copies of tapes to those customers which it has admitted to taping?

- (A) How many customers has Telstra recorded as having had their phone conversations taped without knowledge or consent since 1990? (B) Of these, how many were customers who had compensation claims, including ex Telecom employees, against Telecom?

The nine tapes (the nine smoking guns) mentioned were never released to the four COT Cases, despite FOI requests to all involved parties. The arbitrator made no finding regarding Telstra's unlawful conduct in intercepting my telephone conversations and arbitration-related faxes, even though it was clearly defined in my Letter of Claim that these privacy issues were part of that claim.

Told below and elsewhere on absentjustice.com is my story after the arbitrator, for reasons never explained, did not force Telstra to fix the ongoing telephone problems that brought me to arbitration in April 1994. The government's written findings to that arbitrator on April 13, 1994, and also provided to the Minister for Communications, The Hon Michael Lee MP, was clear Telstra had to be able to prove to the arbitrator there were no more phone problems affecting these services of the COT Cases who chose to have their claims arbitrated on. My arbitration was completed on May 11, 1995, and nothing had changed. The phone problems were worse than when I went into arbitration. The new owners of my business, which they purchased in December 2001, were affecting their business until November 2006, eleven years after the arbitrator concluded his findings, only awarding me losses up to the beginning of my arbitration.

What information was removed from the Malcolm Fraser FOI released document

The AFP believed Telstra was deleting evidence at my expense

During my first meetings with the AFP, I provided Superintendent Detective Sergeant Jeff Penrose with two Australian newspaper articles concerning two separate telephone conversations with The Hon. Malcolm Fraser, former prime minister of Australia. Mr Fraser reported to the media only what he thought was necessary concerning our telephone conversation, as recorded below:

“FORMER prime minister Malcolm Fraser yesterday demanded Telecom explain why his name appears in a restricted internal memo.

“Mr Fraser’s request follows the release of a damning government report this week which criticised Telecom for recording conversations without customer permission.

“Mr Fraser said Mr Alan Smith, of the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp near Portland, phoned him early last year seeking advice on a long-running dispute with Telecom which Mr Fraser could not help.”

One of the questions raised with Malcolm Fraser was: How could Australia say their selling of wheat to the Republic of China was on humanitarian grounds when the Australian government knew that some of this same wheat was being redeployed to North Vietnam? A country that was killing and maiming as many Australian, New Zealand and USA troops as they could during the Vietnam War?

How was this humanitarian when Australia was contributing to the killing of its own soldiers and the soldiers of its Allies in that War?

Telstra released FOI documents showing someone had listened to my telephone conversations with Malcolm Fraser. Could this FOI document be related to Communist China and what the newspaper journalist told me on 18 September 1967, after I had been forced at gunpoint to write about the USA and their war in Vietnam by saying this, I would be a marked man for the rest of my life Chapter 7- Vietnam-Vietcong.

It is evident that Australia's public servants lacked understanding in the 1960s, even up to more recently, of what the people of Communist China felt towards the West during the Mao Zedong reign. Anyone asking questions about their country was ideally seen as spies and therefore targeted, as was I and at least one other crew member of the Hopepeak. I was a good Australian trying to find out which other country was receiving Australian wheat via China's back door. I thought the Australian government would have been pleased to learn what I had uncovered about North Vietnam receiving Australia's wheat. How wrong I was to think Australa's Establishment would have ceased this trade?