Chapter 3 Betrayal - Breach of Trust

PLEASE NOTE:

In my 157-page Statement of Facts and Contentions dated 26 July 2008, which I provided to Mr Friedman (The Judge heating my case) where ACMA on behalf of Telstra and the government did not act in an un-bias manner as the respondants during my Administrative Appeals Tribunal hearing (No V2008/1836). I clearly defined how, for reasons unknown, AUSTEL, (now called ACMA), did not conduct themselves in a properly transparent manner during my 1994/95 arbitration.

This 157-page Statement of Facts and Contentions shows the unethical behaviour of public officials: which included allowing Telstra to support their arbitration defence by using deficient Cape Bridgewater test results that AUSTEL (now ACMA) knew were grossly corrupted, – did not meet the mandatory government spectifications. Yet ACMA allowed this false information to be used by Telstra in their arbitration defence of my claims and in doing discredit the validity of my arbitration submission to the arbitrator.

It is also clear from the same Statement of Facts and Contentions that I highlighted Telstra’s use of the sanitised April 1994 AUSTEL COT Report instead of the later, and more adverse, AUSTEL/ACMA findings (against Telstra). Allowing Telstra to use known fabricated evidence eventually resulted in me being able to conclusively prove to the arbitrator that my telephone faults were still ongoing.

AUSTEL/ACMA's full investigation into my matters between October 1993 and March 1994, clear show AUSTEL/ACMA found that my constant complaining to Telstra benefitted the people of Ballarat and the Portalnd/Cape Bridgewater region.

AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, at points 10, 23, 42, 44, 46, 109, 115, 130, 153, 158, 209 and 212 (below), were compiled after the government communications regulator investigated my ongoing telephone problems. Government records (see Absentjustice-Introduction File 495 to 551) show AUSTEL/ACMA's adverse findings were provided to Telstra (the defendants) one month before Telstra and I signed our arbitration agreement. I did not get a copy of these same findings until 23 November 2007, 12 years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

Page 10 – “Whilst Network Investigation and Support advised that all faults were rectified, the above faults and record of degraded service minutes indicate a significant network problem from August 1991 to March 1993.”

Point 23 – “It is difficult to discern exactly who had responsibility for Mr Smith’s problems at the time, and how information on his problems was disseminated within Telecom. Information imparted by the Portland officer on 10 February 1993 of suspected problems in the RCM “caused by a lighting (sic) strike to a bearer in late November” led to a specialist examination of the RCM on March 1993. Serious problems were identified by this examination.”

Point 42 – “Some important questions are raised by the possible existence of a cable problem affecting the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp service. Foremost of these questions is why was the test call program conducted during July and August 1992 did not lead to the discovery of the cable problem. Another important question is exactly how the cable problem would have manifested in terms of service difficulties to the subscriber.”

Point 44 – “Given the range of faults being experienced by Mr Smith and other subscribers in Cape Bridgewater, it is clear that Telecom should have initiated more comprehensive action than the test call program. It appears that there was expensive reliance on the results of the test program and insufficient analysis of other data identifying problems. Again, this deficiency demonstrated Telecom’s lack of a comprehensive and co-ordinated approach to resolution of Mr Smith’s problems.”

Point 46 –“File evidence clearly indicates that Telecom at the time of settlement with Mr Smith had not taken appropriate action to identify possible problems with the RCM . It was not until a resurgence of complaints from Mr Smith in early 1993 that appropriate investigative action was undertaken on this potential cause In March 1993 a major fault was discovered in the digital remote customer multiplexer (RCM) providing telephone service to Cape Bridgewater holiday camp. This fault may have been existence for approximately 18 months. The Fault would have affected approximately one third of subscribers receiving a service of this RCM. Given the nature of Mr Smith’s business in comparison with the essentially domestic services surrounding subscribers, Mr Smith would have been more affected by this problem due to the greater volume of incoming traffic than his neighbours.”

Point 76 – “One disturbing matter in relation to Mr Smith’s complaints of NRR is that information on other people in the Cape Bridgewater area experiencing the problem has been misrepresented from local Telecom regional manager to more senior manager.”

Point 86 – “From examination of Telecom’s documention concerning RVA messages on the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp there are a wide range of possible causes of this message.”

Point 109 – The view of the local Telecom technicians in relation to the RVA problem is conveyed in a 2 July 1992 Minute from Customer Service Manager – Hamilton to Managers in the Network Operations and Vic/Tas Fault Bureau:

- “Our local technicians believe that Mr Smith is correct in raising complaints about incoming callers to his number receiving a Recorded Voice Announcement saying that the number is disconnecte. They believe that it is a problem that is occurring in increasing numbers as more and more customers are connected to AXE. ”

Point 115 –“Some problems with incorrectly coded data seem to have existed for a considerable period of time. In July 1993 Mr Smith reported a problem with payphones dropping out on answer to calls made utilising his 008 number. Telecom diagnosed the problem as being to “Due to incorrect data in AXE 1004, CC-1. Fault repaired by Ballarat OSC 8/7/93, The original deadline for the data to be changed was June 14th 1991. Mr Smith’s complaint led to the identification of a problem which had existed for two years.”

Point 130 – “On April 1993 Mr Smith wrote to AUSTEL and referred to the absent resolution of the Answer NO Voice problem on his service. Mr Smith maintained that it was only his constant complaints that had led Telecom to uncover this condition affecting his service, which he maintained he had been informed was caused by “increased customer traffic through the exchange.” On the evidence available to AUSTEL it appears that it was Mr Smith’s persistence which led to the uncovering and resolving of his problem – to the benefit of all subscribers in his area”.

Point 153 –“A feature of the RCM system is that when a system goes “down” the system is also capable of automatically returning back to service. As quoted above, normally when the system goes “down” an alarm would have been generated at the Portland exchange, alerting local staff to a problem in the network. This would not have occurred in the case of the Cape Bridgewater RCM however, as the alarms had not been programmed. It was some 18 months after the RCM was put into operation that the fact the alarms were not programmed was discovered. In normal circumstances the failure to program the alarms would have been deficient, but in the case of the ongoing complaints from Mr Smith and other subscribers in the area the failure to program these alarms or determine whether they were programmed is almost inconceivable.”

Point 158 – “The crucial issue in regard to the Cape Bridgewater RCM is that assuming the lightning strike did cause problems to the RCM om late November 1992 these problems were not resolved till the beginning of March 1993, over 3 months later. This was despite a number of indications of problems in the Cape Bridgewater area. Fault reports from September 1992 also indicate that the commencement of problems with the RCM may have occurred earlier than November 1992. A related issue is that Mr Smith’s persistent complaints were almost certainly responsible for an earlier identification of problems with the RCM than would otherwise have been the case.”

Point 209 – “Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp has a history of service difficulties dating back to 1988. Although most of the documentation dates from 1991 it is apparent that the camp has had ongoing service difficulties for the past six years which has impacted on its business operations causing losses and erosion of customer base.”

Point 210 – “Service faults of a recurrent nature were continually reported by Smith and Telecom was provided with supporting evidence in the form of testimonials from other network users who were unable to make telephone contact with the camp.”

Point 211 – “Telecom testing isolated and rectified faults as they were found however significant faults were identified not by routine testing but rather by the persistence-fault reporting of Smith”.

Point 212 – “In view of the continuing nature of the fault reports and the level of testing undertaken by Telecom doubts are raised on the capability of the testing regime to locate the causes of faults being reported.”

AUSTEL/ACMA supplied the quarterly COT Cases Report (see Arbitrator File No/100) to communications minister, the Hon Michael Lee MP, on 13 April 1994. Points 5.31 and 5.32, in this AUSTEL/ACMA report, highlight the continuing phone and fax problems encountered by the four original COT claimants’ businesses and AUSTEL/ACMA directed Telstra to carry out the SVTs at claimants’ premises using AUSTEL/ACMA specifications, to verify the phone services were now operating at proper working standard, but this did not eventuate. (See Open Letter File No/22)

On 15 July 1995 AUSTEL/ACMA's previous General Manager of Consumer Affairs provided me with an open letter noting:

“I am writing this in support of Mr Alan Smith, who I believe has a meeting with you during the week beginning 17 July. I first met the COT Cases in 1992 in my capacity as General Manager, Consumer Affairs at Austel. The “founding” group were Mr Smith, Mrs Ann Garms of the Tivoli Restaurant, Brisbane, Mrs Shelia Hawkins of the Society Restaurant, Melbourne, Mrs Maureen Gillian of Japanese Spare Parts, Brisbane, and Mr Graham Schorer of Golden Messenger Couriers, Melbourne. Mrs. Hawkins withdrew very early on, and I have had no contact with her since.

The treatment these individuals have received from Telecom and Commonwealth government agencies has been disgraceful, and I have no doubt they have all suffered as much through this treatment as they did through the faults on their telephone services.

One of the striking about this group is theur persistence and enduring beleif that eventually there will be a fair and equitable outcome for them, and they are to admired for having kept as focussed as they have throughout their campaign.

Having said that, I am aware all have suffered both physically and their family relationships. In one case, the partner of the claimant has become seriously incapacitated; due, I beleive to the way Telecom has dealt with them. The others have al suffered various stress related conditions (such as a minot stroke.

During my time at Austel I pressed as hard as I could for an investigation into the complaints. The resistance to that course of action came from the then Chairman. He was eventually galvanised into action by ministerial pressure. The Austel report looks good to the casual observer, but it has now become clear that much of the information accepted by Austel was at best inaccurate, and at worst fabricated, and that Austel knew or ought to have known this at the time.”

After leaving Austel I continued to lend support to the COT Cases, and was instrumental in helping them negotiate the inappropriately named "Fast Track" Arbitration Agreement. That was over a year ago, and neither the Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman nor the Arbitrator has been succsessful in extracting information from Telecom which would equip the claimants to press their claims effectively. Telecom has devoted staggering levels of time, money and resources to defeating the claiams, and there is no pretence even that the arbitration process has attemted to produce a contest between equals.

Even it the remaining claimants receive satisfactory settlements (and I have no reason to think that will be the outcome) it is crucial that the process be investigated in the interest of accountabilty of publical companies and the public servants in other government agencies.

Because I am not aware of the exact citrcumstances surronding your meeting with Mr Smith, nor your identity, you can appriate that I am being fairly circimspect in what I am prepared to commit to writing. Suffice it to say, though, I am fast coming to share the view that a public inquiry of some discripion is the only way that the reasons behind the appalling treatent of these people will be brought to the surface.

I would be happy to talk to you in more detail if you think that would be useful, and can be reached at the number shown above at any time.

Thank you for your interest in this matter, and for sparing the time to talk to Alan. (See " File 501 - AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541 )

Amanda Davis would not reveal more in her letter because I had already advised Ms Davis that I thought it was best she not know the name of the person who had agreed to meet with me, in the public interest. By operting in this manner it protected all parties from being accused of collusion or compromising a situation that was alarming top say the least. The fact that neither the Australian Federal Police, the Commonwealth Ombudsman, Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, the arbitrator and the Australian Senator had been able to stop Telstra threatening me during my previous arbitration or hold Telstra accountable after they carried out those threats was the reason I was being careful (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

On 28 September 1992, when Amanda Davis was AUSTEL/ACMA's General Manager of Consumer Affairs, she telephoned me to discuss evidence I had mailed to AUSTEL/ACMA some days previous (see two File 14 - AS-CAV Exhibit 1 to 47. The first document in File 14 is a typed Telstra fault record showing several faults experienced on my incoming phone service line 055 267 267, including three calls from Amanda Davis. It is clear from the discussion on this typed fault record that the first two S-D long-distance calls both calls dropped out where it is noted Amanda Davis only heard the pips on the line but did not connect on either call. Her third call was successful. However, it is confirmed from File 14 that Amanda Davis was charged for both no-connected calls. The second File 14 is the handwritten fault recording from Telstra of the events shown on the printed File 14.

It is further confirmed from File 122-A to 122-G - AS-CAV Exhibit 92 to 127 that AUSTEL and Telstra knew a national billing problem in Telstra's 008/1800 billing software as early as 1993.

It is also important to note from File 210-C AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233 a three-page internal report prepared by AUSTEL on 26 February 1996, which was derived from the evidence AUSTEL collected from my business on 19 December 1995 that they acknowledge my claims of ongoing 008/1800 billing problems was a valid claim. File 210-D AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233 dated 2 August 1996 confirms the 008/1800 billing short duration lock-up billing problems were still apparent. In other words, the 008/1800 billing problem I raised with AUSTEL in June 1993 was still in the Telstra network for more than three years.

The following link CAV Exhibit 92 to 127) confirms Frank Blount, Telstra’s CEO, after leaving Telstra he co-published a manuscript in 1999. entitled, Managing in Australia. On pages 132 and 133, the author exposes the problems Telstra were hiding from their 1800 customers:

“Blount was shocked, but his anxiety level continued to rise when he discovered this wasn’t an isolated problem.

The picture that emerged made it crystal clear that performance was sub-standard.” (See File 122-i - CAV Exhibit 92 to 127)

Frank Blount's Managing Australia https://www.qbd.com.au › managing-in-australia › fran can still be purchased online.

I reiterate, the fact that the Telstra Board knew Telstra had a systemic network billing software problem and still advises the government on 11 November 1994 (see File 46-G - Open letter File No/46-A to 46-l, they would address these 008/1800 problems during my arbitraton and neither Telstra or the arbitrator adressed my 008/800 billing claim documents during my arbitration allowing them to be addressed secretly five months after my arbitration had not addressed them (see Absent Justice Part 2 - Chapter 14 - Was it Legal or Illegal? is testament Australia's government minders need to step up and admit how wrong they have been concerning my 008/1800 claims.

According to Section 52 of the Australian Trade Practices Act under Part V - Consumer Protection Division 1 - Unfair Practices - Misleading or deceptive conduct:

- 52. (1) "A corporation shall not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive"

Telstra/ACMA collectively has continued to conceal their knowledge that I had a valid claim against Telstra under the Trade Practices Act, when that false 008/1800 billing advice was provided to AUSTEL 16 October 1995. The current government regulator ACMA and the Minister The Hon Paul Fletcher should treat this misleading and deceptive conduct towards me as a matter of some concern. The government regulator breached their statutory obligation to me, by concealing their knowledge that Telstra misled and deceived the government under the Trade Practices Act when supplying this false 008/1800 submission. Espercially since Frank Blount's book (See File 122-i - CAV Exhibit 92 to 127) confirms Telstra did have a major 008/1800 problem and yet Telstra concealed their knowledge of this from firstly the arbitrator, secondly from me the claimant and the government who owned Telstra.

There is no statute of limitations under Section 52 of the Trade Practices Act under the citcumstances of which this misleading and deceptive conduct that took place on 16 October 1995, when the entire Telstra board mislead and deceived AUSTEL concerning my 008/1800 billinging problems when Frank Blounts book Managing in Australia shows my claims were valid.

Had the Government Communications Regulator AUSTEL/ACMA not concealed their Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp covert report from the Minister for Communications and the arbitrator, the arbitrator would have been compelled to investigate as to whether my claims of ongoing billing problems was a valid claim. Below are just some examples of the information concealed from the arbitrator.

Before the arbitrations actually began

Before the arbitrations actually began, the arbitrator was provided with a report that was officially submitted to all parties involved in the first four arbitrations as well as various government ministers. This report, dated 13 April 1993, states, at point 5.78: “an agreed standard of service, being developed in consultation with AUSTEL to be applied to any case subject to settlement is essential”. It is clear from this 258-page report, and other similar statements made by AUSTEL/ACMA, that no finding by the arbitrator could be brought down until Telstra had proved it had fixed all of the ongoing telephone problems being experienced by those entering settlement and/or arbitration. After all, what was the purpose of an arbitration process if the claimants’ businesses were still affected by the ongoing problems that brought them into the process in the first place?

Point 5.25, 5.29 and 5.32 in this public report (see AUSTEL Evidence File 1-A states:

“…Mr Smith was the first of the original COT Cases to reach an initial ‘settlement with Telecom. It is understood that he: identified the type of faults which his business had experienced. Mr Smith has informed AUSTEL that his major concern and stipulated condition at the time of ‘settlement’ was that his service should operate, and continue to operate, at normal standards”.

“The fifth of the original COT Cases, Mr Schorer, had particular concerns about Telecom’s limited liability and the impact that the limitations was likely to have on any claim he might make for compensation arising from an inadequate telephone service.

“The fact that faults continued to impact upon the businesses in the period following the settlement shows a weakness in the procedures employed. That is a standard of service should have been established and signed off by each party. It is a necessary procedure of which all parties are now fully conscious and is dealt with elsewhere in this report. Its omission as far as the initial ‘settlement’ of the original COT Cases were concerned meant that there was continued dissatisfaction with the service provided without any steps being taken to rectify it. This inevitably led to a dissatisfaction with the initial ‘settlement’ and to further demands for compensation. To avoid this sort of problem in the future, AUSTEL is, in consultation with Telecom, developing –

- a standard of service against which telecom’s performance may be effectively measured;

- a relevant service quality verification test.

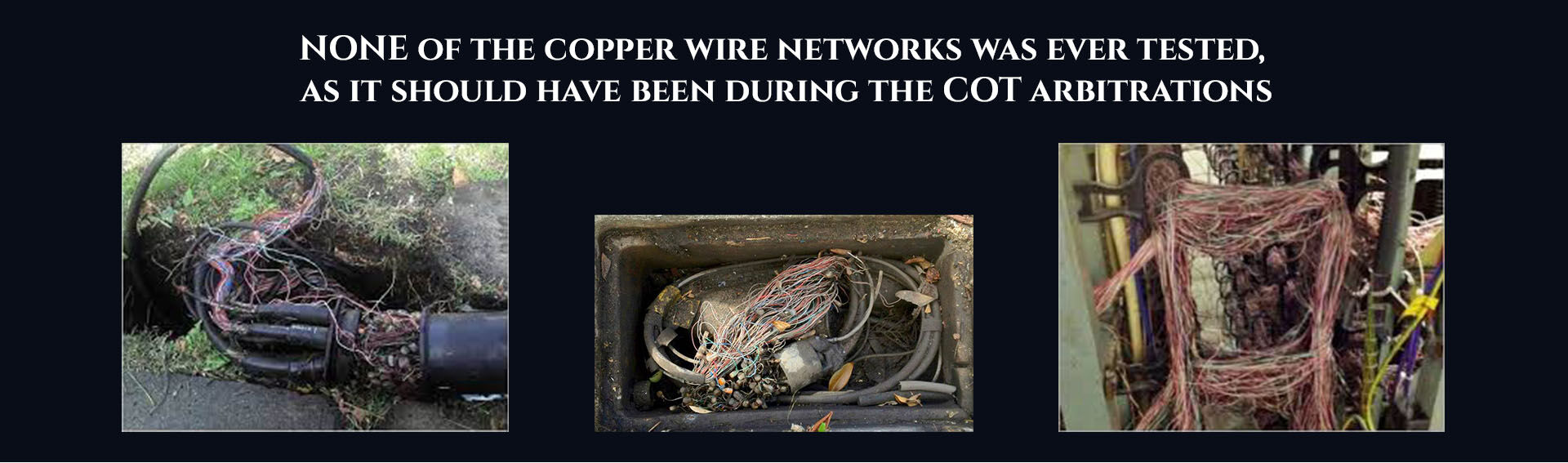

In the case of at least six of the Service Verification Tests conducted at the COT-cases businesses including my businesses, NO supervised testing of those service lines were carried out by anyone other than the defendants Telstra i.e. NO independent arbitration umpire was present when these tests used by Telstra as defence documents were in attendance when they were conducted. As shown in my own report titled Telstra’s Falsified SVT Report, Telstra fabricated their Cape Bridgewater SVT arbitration testing.

The attachments accompanying my reply to Telstra’s arbitration defence, which I provided to Dr Hughes in person and were never returned to me after my arbitration, confirm I challenged Telstra arbitration engineer Peter Gamble’s witness statement of 12 December 1994, in which he states he conducted the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp SVT testing and exceeded all of AUSTEL/ACMA specifications. (See Telstra’s Falsified SVT ‘unmasked identities’) Dr Hughes’ award findings made NO comment on my challenge stating Mr Gamble perverted the course of justice when he submitted his report. Introduction File No/4-A and File No/4-B, the CCAS data (File No/4-F) and the falsified SVT information all confirm Mr Gamble mislead and deceived the arbitration process concerning the not-tested Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp services.

The Senate Hansard (see Introduction File No/6) of 24 June 1997 confirms ex-Telstra employee, turned whistleblower, advised a Senate committee, under oath, that Peter Gamble was one of the two Telstra employees who told him the first five COT cases (and naming me as one of the five) had to be stopped at all cost from proving our claims.

The fact that Dr Hughes disallowed his own technical consultants the extra time they required to investigate my complaints of ongoing telephone problems, including my claims the SVT process was aborted, suggests Dr Hughes was clearly biased. My arbitration lawyers also thought the same (see Open Letter File No/51-C).

On 9 March 1995, after the Telstra Corporation had offered DMR (Australia), the arbitration technical consultants, an offer they could not possibly refuse and they pulled out of the COT arbitration process – leaving the COT cases stranded with no one in Australia left who they believed Telstra would not compromise. We four COT cases wanted to amend our claims and at the same time call for a halt until an honest technical broker could be found: impossible in the current situation with Telstra commanding power over most, if not all, of the technical consultants in Australia.

As a compromise, to avoid delaying the arbitration process, the TIO wrote to the four COT cases advising us Paul Howell of DMR Group Inc in Canada had agreed to be the principal technical advisor to the resource unit if we accepted Lane. David Read of Lane was ex-Telstra and therefore the COT cases should never have been placed in a position of having to accept Lane. We received many telephone calls and correspondence from the TIO, promising us that DMR (Canada) would be the principal consultants and assuring us our concerns would be looked after in this matter. Eventually, we accepted Lane as assistants to DMR,

It is quite obvious from the varying draft findings by Lane Telecommunications and the comparing of the DMR (Canada) and Lane Australia final report dated 30 April 1995, that Lane was secretly allowed to do all of the assessment to my arbitration claim material as well as conduct all site visits to the Portland and Cape Bridgewater telephone exchanges and my business premises. In effect, the TIO, those who took orders from him and the arbitrator, sold us out.

The AUSTEL report confirms the SVT process was to give the arbitrator a guide as to whether all problems registered by the COT claimants had been located and rectified. The arbitrator was unable to hand down his final decision until Telstra demonstrated that it had carried out the specified SVTs and proved to AUSTEL/ACMA’s satisfaction that both phone and fax services to various COTs’ businesses were up to the expected network standard.

Even though AUSTEL/ACMA expressed serious concerns about the obvious deficiencies in the SVT run at my business, Telstra still used these test result to support its arbitration defence. On 16 November 1994, AUSTEL/ACMA wrote to the Telstra arbitration liaison officer under the heading Service Verification Test Issues, outlining its concerns regarding the deficiencies in the testing process conducted at the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp (see Main Evidence File No/2). Telstra’s CCAS data for the day testing took place at my premises (29 September 1994) confirms not one of the incoming tests connected to any of my three business lines met the regulator’s mandatory requirements.

In AUSTEL/ACMA’s 16 November 1994 letter, it warned Telstra the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp SVT process was deficient. By the time I received this AUSTEL/ACMA letter, in 2002, the statute of limitations allowing me to use this information in an appeal had expired. It is clear from Main Evidence File Nos/2 and 3 the SVT process at Cape Bridgewater Camp was not performed according to the regulator standards.

In response to AUSTEL/ACMA’s letter noting Telstra’s SVT process was grossly deficient (see Main Evidence File No/2), the Telstra technician who performed the tests – and who was also part of the management team – replied. In his 28 November 1994 letter to the government communications regulator, he stated:

“As agreed at one of our recent meetings and as confirmed in your letter of 16th November 1994, attached please find the detailed Call Delivery Test information for the following customers. …

“This information is supplied to Austel on a strict Telecom-in-Confidence basis for use in their Service Verification Test Review only and not for any other purpose. The information is not to be disclosed to any third party without the prior written consent of Telecom.” (See Arbitrator File No/98)

By what legal authority could this Telstra bureaucrat insist on confidentiality when Telstra was the defendant in my arbitration? How could a bureaucrat tell a government regulator what they could or could not do during an arbitration process?

In October 2008 and May 2011, the Administrative Appeals Tribunals (AAT) heard my two Melbourne FOI matters. The government communications regulator (AUSTEL/ACMA) was the respondent on both occasions. I had still not received my promised discovery arbitration documents from 1994. Later changes to Australian law render this authority irrelevant, so how can Telstra require confidentiality from AUSTEL employees working for the government communications regulator? Arbitrator File No/110 is one of two SVT testing documents discussed in the 29 November 1994 letter from Telstra to AUSTEL. These two Call Charge Analyses System (CCAS) data printouts show there were not 20 mandatory SVT tests calls generated into each of my three service lines on 29 September 1994. That day, this particular Telstra engineer’s SVT monitoring equipment malfunctioned. The 60 test calls that were required to check faults on these three service lines, were not carried out: the lines were not held open for the 100-120 seconds required to fully test their functioning capabilities.

This same Telstra technician was named in the Senate Estimates Hansard of 24 June 1997 as advising Telstra employees that the five COT cases (including me) had to be “stopped at all costs” from proving the validity of our claims (see Open Letter File No/24). As part of my AAT submission, I provided both AAT and ACMA with a 156-page Statement of Facts and Contentions, plus a CD containing some 440 supporting exhibits. The ACMA chair and lawyers were given proof the author of the 28 November letter dictated what government regulators could or could not do during my government-endorsed arbitration, and that the writer swore, under oath (on 12 December 1994), the SVT tests exceeded AUSTEL/ACMA's specifications. The ACMA chair failed to act on this incriminating evidence. Arbitrator File No/110, Main Evidence File No 3 and the letter of 28 November 1994 (see Arbitrator File No/98) support my claims against certain public servants, employed by AUSTEL, who assisted Telstra to pervert the course of justice during my arbitration. Mr Friedman, senior AAT member, after hearing my claims, found them neither frivolous nor vexatious and supported my quest for justice.

Between 24 February 2008 and 14 January 2009, more than 15 letters addressed to various ACMA lawyers and the chair of ACMA show contradictions in Telstra’s SVT reports and its sworn witnesses’ statements. The documents provided during my arbitration process (which was known to be grossly deficient) were handed to both AAT and ACMA as part of the AAT submission. I also included proof that another set of tests – the Bell Canada International Inc (BCI) tests – submitted as evidence by Telstra during my arbitration – were also impracticable (see Telstra’s Falsified BCI Report masked identities and Main Evidence File No 3).

This matter was not investigated in conjunction with the deficient Cape Bridgewater SVT process. Two reports – one dated 10 November 1993, the other October 1994 – were both proved grossly inaccurate, yet the arbitrator relied solely on them and furthermore, accepted them as factual evidence. The senior executives of AUSTEL/ACMA have been shown to be clearly negligent in their duties: this has had grave repercussions for all COT cases, particularly me. It has also had further repercussions for the general public and the integrity of the organisation they represent.

On 2 February 1995, one of AUSTEL/ACMA’s bureaucrats attached COT Cases AUSTEL/ACMA third quarterly report to his letter to the Hon Michael Lee, Minister for Communications and the Arts, which states:

“Service Verification Tests have been completed for seven customers. Reports have been completed and forwarded to six of the customers, and the seventh report is in preparation. All six of the telephone services subjected to the Services Verification Tests have met or exceeded the requirements established.” (See Open Letter File No/23)

It is important to consider this quarterly report in light of the letter AUSTEL wrote to Telstra’s arbitration liaison officer on 16 November 1994 (see Main Evidence File No/2) advising the SVTs conducted at the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp were deficient and asking Telstra what they intended to do regarding this deficiency in the testing procedure.

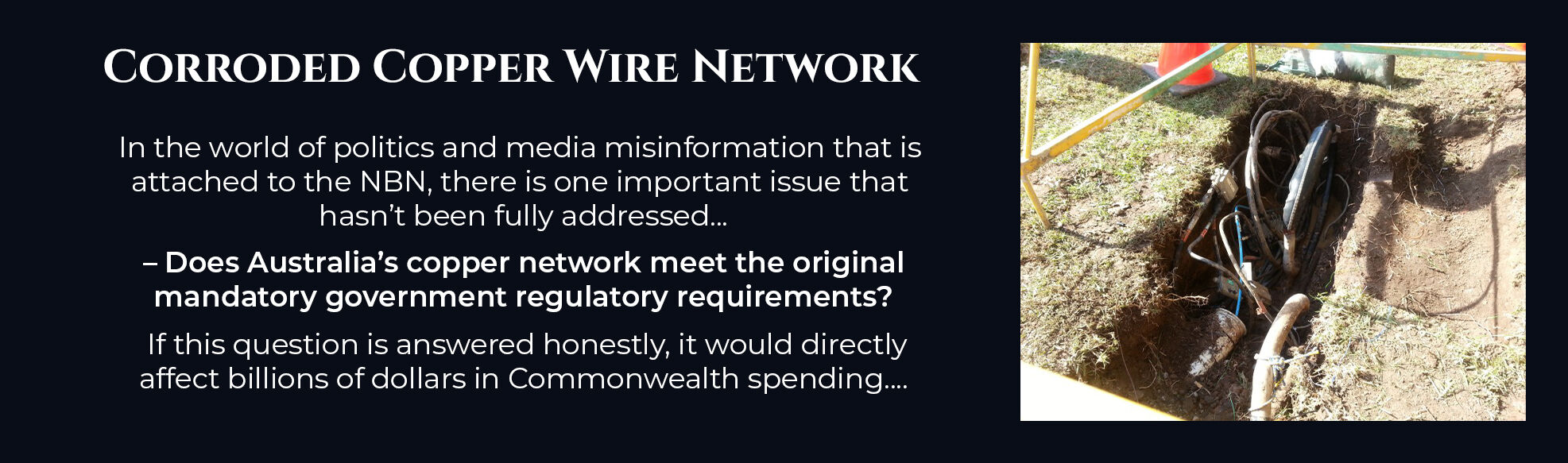

Corroded Copper Wire Network

In the world of politics and media misinformation that is attached to the NBN, there is one important issue that hasn’t been fully addressed – Does Australia’s copper network meet the original mandatory government regulatory requirements? If this question is answered honestly, it would directly affect billions of dollars in Commonwealth spending. Why? Well, most of the current government’s NBN policy is based on using the existing copper network to get the internet to businesses and residences, a process dubbed Fibre-to-the-Node (FTTN). The government has apparently chosen to go down this path because this how other countries upgraded from their copper networks and because the FTTN process is expected to provide the most productivity from the ailing networks before eventually switching to Fibre-to-the-Premises.

This situation however would have been quite different if the government regulator had ordered Telstra to purchase the correct Service Verification Testing (SVT) equipment needed to carry out the required COT arbitration testing (See Telstra’s Falsified SVT Report ‘unmasked identities’). Instead, Telstra left the choice of testing equipment to Bell Canada International Inc. and agreed to limit testing to calls to the main exchange, instead of the CAN – the copper wire between the exchange and the customer’s premises. Does this mean then that the Commonwealth government is actually responsible for what is now a major national telecommunication problem?

If Bell Canada had carried out the full end-to-end CAN testing, they would have certainly been able to warn Telstra and AUSTEL/ACMA that an upgrade of the copper-wire network needed to begin immediately, in 1993. Just imagine where the telephone system would be in Australia today, if that had happened 23 years ago!

Although that didn’t happen, it could have because, early in 1994 (before the Casualties of Telstra arbitrations), I discovered Telstra had not told Bell Canada that the unmanned Bridgewater exchange, which all calls were routed through, could not handle the testing equipment BCI claimed to have used to generate the calls. If Bell Canada had known what that unmanned exchange could handle, then they may well have discovered it was the unmanned exchange’s corroding copper-wire network that was partly responsible for the Recorded Voice Message, “The number you are ringing is not connected,” that was ruining my business. That discovery might have led Bell Canada to realise Telstra was using them to cover-up how bad the rural network actually was, right around Australia.

We know Telstra deliberately misled the Senate estimates committee in September 1997 by providing false information in response to questions on notice and that the same thing happened again in October 1997. Since the Senate committee asked their questions on notice, they would have been compelled to advise the government Telstra, at the very least, had conjured up their Cape Bridgewater testing results. This major exposé would have led to more investigations and those investigations would surely have found that, in 1993, although the government ordered testing of the COT cases’ exchanges, this so-called testing was nothing but a total scam and that would have meant that the upgrading of Telstra’s rural network could have commenced sometime in 1997.

Australia is now footing an expense that would have cost much less (probably by billions) than what it now costs, 23-odd years later, all because of the misleading and deceptive advice that Telstra gave the Senate estimates committee hearing in October 1997.

Australia’s copper broadband infrastructure: view

Service Verification Test Part-One

Any reasonable-minded commercial assessor, after seeing photos similar to the one shown or written advice from Telstra’s technical field staff explaining how bad the copper wire network was, would have demanded Telstra supply the four COT cases with evidence: evidence the Commonwealth Ombudsman, on 20 January and 24 March 1994 (see Bad-Bureaucrats-File-No/20), also demanded Telstra address regarding the four COT cases being denied access to documents supporting their claims. Had the assessor been truly independent, he would not have moved forward and/or allowed the claimants to abandon their assessment process until the four claimants received the requested evidence. As our webpage absentjustice shows, the arbitrator did not seek those documents through the commercial assessment process in order for the four claimants to see whether they had enough documented evidence to proceed with arbitration. The Front Page of absentjustice.com shows both Senator Ron Boswell, on 20 September 1995, and Senator Alan Eggleston, on 23 March 1999, advised the Senate the COTs were forced into arbitration without the necessary documents to support their claims. With this admission by two senators, why do these COT cases’ claims remain unresolved?

Twenty Years Later

On 29 January 2014, CEPU representatives publicly showed similar photos to the one opposite demonstrating problems with the Telstra copper network, including some of the innovative solutions technicians had used.

During the lock-up meeting at AUSTEL/ACMA’s Queens Road office, Melbourne mentioned above, we discussed the aging network and alerted AUSTEL/ACMA that in our opinion would continue to affect customers if Telstra did NOT carrier out proper CAN maintenance. Neither the chair nor the general manager of consumer affairs were shocked at the Freedom of Information documents we produced at this meeting showing Telstra had full knowledge it had major network problems in the customer access network similar to the one shown by the CEPU representatives. AUSTEL/ACMA changed the subject and, in a roundabout way, the general manager of consumer affairs advised us the documents I had shown AUSTEL/ACMA concerning the ongoing 008/1800/freecall problems were even worse than the estimated more than 120,000 COT-type complaints AUSTEL/ACMA originally recorded. Unfortunately, during our arbitrations, as the conjured BCI and SVT tests showed our phone lines were now ‘fixed’, the arbitrator ignored our documentation.

It is also important to link how AUSTEL/ACMA withheld its findings from the Hon Michael Lee MP, on 2 February 1995, regarding the deficient SVT conducted at my business with the way they also withheld information from the same minister regarding adverse findings concerning my business losses (see Main Evidence File No 15).

Everyone has, at some time, reached a recorded voice announcement (known within the industry as an RVA):

‘The number you have called is not connected or has been changed. Please check the number before calling again. You have not been charged for this call.’

This incorrect and misleading message was the RVA people most frequently reached when trying to ring my camp. While Telstra never acknowledged this, I discovered much later, among a multitude of FOI documents I received in 1994, a copy of a Telstra internal memo confirming, “this message tends to give the caller the impression that the business they are calling has ceased trading, and they should try another trader”.

Another Telstra document referred to the need for “a very basic review of all our RVA messages and how they are applied … I am sure when we start to scratch around we will find a host of network circumstances where inappropriate RVAs are going to line”.

It seems the ‘not connected’ RVA came on whenever the lines in or out of Cape Bridgewater were congested, which, given how few lines there were, was often.

It is well established in AUSTEL/ACMA archives that I claimed the 008/1800 billing problems raised prior to and during my arbitration was a two fold problem;

Firstly, we had the known Ericsson AXE lockup fault in the system. When the AXE phone survived locked up, this often created the terminated call to register for a further 90 seconds until after each call had ended. Just think of all the extra revenue Telstra made from its customers because of a 90-second delay in terminating each call?

Secondly, my 008/1800 service line (which was trunked through the Portland AXE telephone exchange also had a known software lockup which kept the line open from 3 seconds, 10 seconds even up 16 seconds before terminating. Telstra was wrongly billing their customers for seconds that they did not use.

Thirdly, one of the problems associated with these two different lockup faults is that once a customer could not get through the period, the lines were locked up, the person ringing through often received a recorded message telling them the number they just called was not connected.

For a newly established business like ours to have so many faults, was a major disaster, but despite the memo’s acknowledgement that such serious faults existed, Telstra never admitted the existence of a fault in those first years. And, with my continued complaints, I was treated increasingly as a nuisance caller. This was rural Australia, and I was supposed to put up with a poor phone service – not that anyone in Telstra admitted that it was poor service. In most cases, ‘No fault found’ was the finding by technicians and linesmen.

Next Page ⟶