This website absentjustice.com / absentjustice.com.au and promoteyourstory.com.au is a work in progress, last edited in December 2025

If you understand the profound significance of this research and the invaluable insights it brings to light, we encourage you to support Transparency International! Your contributions will be instrumental in amplifying awareness of the injustices that jeopardize the very foundations of democracy across the globe. Together, we can shine a spotlight on corruption and advocate for transparency, accountability, and justice. Thank you for your interest and your commitment to this essential cause.

Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia.

Shameful, hideous, and treacherous—just a few words that describe these lawbreakers. Unscrupulous, vile, and corrupt actions within the government have undermined the arbitration system in Australia, a system the government itself had endorsed. The question remains: is the Institute of Arbitrator Mediator Australia (IAMA) biased and lacking transparency? Click this link—the eleventh remedy pursued—and form your own opinion.

Delve into the unsettling realm of egregious crimes and heartless criminals, where the lines between justice and corruption blur.

Discover the corrupt government officials who exploit their power, alongside politicians and lawyers who, often unknowingly, become entangled in this web of deceit. These individuals manipulate critical government decisions and exert influence over the legal processes in our courts and arbitration centres—undermining the very fabric of justice.

Chapter: The Arbitraitor – Shadows of Betrayal

Many readers might be tempted to believe that the manipulation of Australia’s arbitration system and the corruption within government were relics of the 1990s—resolved, forgotten, and buried in history. That belief is a dangerous illusion. The truth is far darker. The sinister underbelly of Australian politics and arbitration remains alive, with the Institute of Arbitrators and Mediators Australia (IAMA) as its public face (See the eleventh remedy pursued). Wrongdoings by some of its members continue to taint the organisation, rotting in a cesspool of deceit and treachery. The link to the eleventh remedy pursued stands as undeniable proof of this decay.

The Betrayal

The IAMA possessed clear evidence of Dr Hughes’ gross misconduct. Yet instead of exposing him, the organisation chose protection—shielding both Hughes and itself at the expense of justice. This blind protection destroyed the lives of many COT Cases, myself included. Families were left broken, livelihoods ruined, and faith in the system shattered. The betrayal was not a single act but a pattern of concealment, a deliberate refusal to confront corruption.

Open Letter dated 25 September 2025 → "The first remedy pursued"

In 2025, Dr Gordon Hughes is Principal Lawyer of Davies Collison Cave's Lawyers Melbourne → https://shorturl.at/L4tbp

The long journey to my forthcoming ebook, The Arbitraitor, to be launched on >www.promoteyourstory.com.au< on 17 or 28 December 2025, underscores why understanding “the first remedy pursued” is essential. It illuminates the foundations of our struggle and the implications for all who have been affected by institutional silence and betrayal.

😈 The Devil's letters → the first remedy pursued

What dark motives drove the arbitrator, Dr Gordon Hughes, Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman John Pinnock, and arbitration project manager John Rundell to engage in such treachery? These so-called "pillars of society" conspired to weave a web of deceit, crafting letters laden with malicious lies. It is nothing short of appalling that Dr Hughes allowed his wife’s good name to be manipulated by John Pinnock in their desperate attempt to hide their malevolent actions from Laurie James, President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia. This act of betrayal is among the most contemptible imaginable.

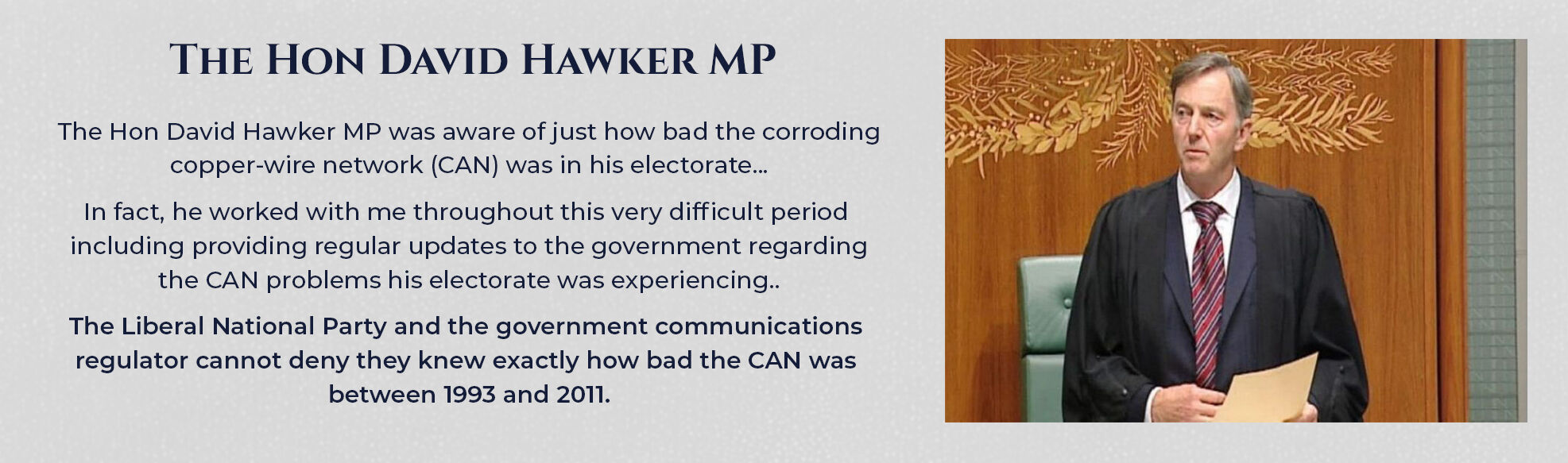

John Pinnock’s second dishonest letter, one of four authored by this unscrupulous trio, effectively halted an investigation that could have validated my claims of persistent telephone problems. Instead, their calculated deceit has festered for over three decades. In this letter to The Hon. David Hawker MP, Pinnock falsely claimed that my billing issues had been resolved during arbitration by May 11, 1995. However, the information available on absentjustice.com starkly reveals that these problems continued until at least November 2006—eleven long years after my arbitration had concluded.

When Pinnock sent this misleading letter to The Hon. David Hawker MP in March 1996, he had already received damning evidence from AUSTEL, the government communications authority, in a letter dated August 3, 1995 (see 46-K Open letter File No/46-A to 46-l). This letter clearly stated that my ongoing 1800 billing arbitration issues had not yet been addressed, yet Pinnock chose to ignore it, perpetuating a reign of deception. The depth of this corruption is alarming, highlighting a willingness to sacrifice integrity and truth.

In fact, neither John Pinnock nor Telstra would investigate my ongoing complaint through to 2001, telling the government my 1994/95 arbitration had fixed my ongoing telephone problems. In desperation, my partner and I sold the business in December 2001 for land value only, because there was no goodwill left sell. Darren and Jenny Lewis took the gamble and lost, as the following exhibit shows → See Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story.

Remember to hover your mouse or cursor over the images as you scroll down the homepage.

Who hijacked my original 1994 BCI and SVT arbitration reports in 1994 and then again in 2008?

The Book as Reckoning

Our forthcoming book, 'The Arbitraitor', slated for release on 17 or 18 December 2025 (see www.promoteyourstory.com.au), is the culmination of years of struggle. It endured four intense rounds of writing and editing, each one peeling back another layer of deception. What emerged was not a simple timeline but a labyrinth of corruption entangling Telstra, government officials, and arbitration insiders. The narratives were so convoluted—filled with secrecy, intimidation, and underhanded tactics—that a straightforward chronological account became impossible.

The Evidence Files

Each betrayal twisted itself around multiple arbitrations, sometimes ensnaring three or four cases at once. To make sense of the chaos, we dissected these accounts into separate sections. Our journey was further obstructed by the daunting challenges posed on the website absentjustice.com. There, we fought to weave together a multitude of dark mini‑stories (see Evidence File 1, Evidence File 2, Evidence File 3, and potentially Evidence File 6 or 7, depending on whether the Australian government acknowledges that my arbitration was grossly mishandled).

One of the fourteen government and non‑government agencies to which I wrote, attaching clear evidence that the Telstra Corporation committed a crime, comprised 67 evidence files. Some were numbered from A to K, meaning that one block of proof might consist of 10 documents, which I attached to the report addressed to Australia’s ACCC in 2011.

Because this one report should have opened an investigation into my claims and nothing was done, I will submit this 68‑page report and its evidence files as a single document titled Evidence File 2.

I ask you to keep a watch out for this file, as it should be on my new website — www.promoteyourstory.com.au — by Christmas Day.

I reiterate, who hijacked my original 1994 BCI and SVT arbitration reports in 1994 and then again in 2008?

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

I have never received a written response from BCI, but the Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

The False Award

The arbitrator, fully aware of the deep-rooted corruption pervading the case, chose to turn a blind eye before issuing his formal award on May 11, 1995. In a betrayal, he deceitfully presented the DMR & Lane technical report as a definitive set of findings, despite the glaring fact that only 23 assessments had been conducted by the consultants. This misrepresentation was not an oversight; it was a calculated ploy to obscure the truth.

“Continued reports of 008 faults up to the present. As the level of disruption to overall CBHC service is not clear, and fault causes have not been diagnosed, a reasonable expectation that these faults would remain ‘open’,” (Exhibit 45-c -File No/45-A)

Point 209 – “Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp has a history of service difficulties dating back to 1988. Although most of the documentation dates from 1991 it is apparent that the camp has had ongoing service difficulties for the past six years which has impacted on its business operations causing losses and erosion of customer base.”

Point 210 – “Service faults of a recurrent nature were continually reported by Smith and Telecom was provided with supporting evidence in the form of testimonials from other network users who were unable to make telephone contact with the camp.”

Point 211 – “Telecom testing isolated and rectified faults as they were found however significant faults were identified not by routine testing but rather by the persistence-fault reporting of Smith”.

Point 212 – “In view of the continuing nature of the fault reports and the level of testing undertaken by Telecom, doubts are raised on the capability of the testing regime to locate the causes being reported.”

“Let me just say, I don’t consider you, personally, to be frivolous or vexatious – far from it.

“I suppose all that remains for me to say, Mr Smith, is that you obviously are very tenacious and persistent in pursuing the – not this matter before me, but the whole – the whole question of what you see as a grave injustice, and I can only applaud people who have persistence and the determination to see things through when they believe it’s important enough.”

The IAMA unearthed these truths during its third investigation in 2009, following a shadowy inquiry that began in 1996. What now lies hidden will send chills down the spines of readers of absentjustice.com as they peek behind the evidence files I provided to the IAMA Ethics and Professional Affairs Committee between July and November 2009 (see ). These files reveal corruption not as a relic of the past but as a living, breathing force that continues to shape outcomes today.

Conclusion: Justice Delayed, Truth Preserved

The Arbitraitor is not merely a book—it is a reckoning. It forces readers to confront corruption that has festered for decades, reminding us that justice delayed is justice denied. The evidence files, preserved against all odds, stand as proof that truth cannot be erased. They are the lifeline of accountability, ensuring that even when institutions fail, the record of betrayal remains to be exposed.

This project has endured a harrowing evolution, navigating through a relentless maze of writing and editing to expose the sinister truths lurking in the shadows. The deep-rooted corruption entwining Telstra with the key figures in the arbitration process demanded painstaking revisions. The narratives we uncovered formed a twisted and treacherous web—saturated with deceit, secrecy, intimidation, and nefarious tactics—so convoluted that any straightforward chronological account became nearly impossible.

At point 2.3 in the arbitrator's draft award, he states:

"Although the time taken for completion of the arbitration may have been longer than initially anticipated, I hold neither party nor any other person responsible. Indeed, I consider that the matter has proceeded expeditiously in all the circumstances. Both parties have cooperated fully."

On the right side of this statement's column, a handwritten note reads, "Do we really want to say this?"

While there's a point 2.2 in Dr Hughes final award, there's no point 2.3.

On September 26, 1997, John Pinnock, the second appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman and the second administrator of the COT arbitrations, formally addressed a Senate estimates committee. He noted on page 99 of the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia Hansard record that:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

The Fallout

The words Pinnock delivered on 26 September 1997 did not vanish into the sterile air of the Senate chamber. They lingered, heavy and corrosive, like smoke that clings to the walls long after the fire has gone. For the claimants of the COT Cases, his testimony was more than bureaucratic doublespeak — it was confirmation that the arbitration process had been hijacked, twisted into something unrecognisable.

Behind the polished veneer of procedure, the machinery of justice had been dismantled. The arbitrator, stripped of control, had become a figurehead, while unseen hands operated the levers in secret. The agreements signed in good faith were now revealed as traps — contracts that promised fairness but delivered betrayal.

The senators shifted in their seats, some scribbling notes, others staring at Pinnock with the kind of suspicion reserved for men who speak too smoothly. His calm delivery was the mask of a man who knew more than he was willing to admit. The contempt in his tone was unmistakable, as though the claimants' suffering were a nuisance, an inconvenience to be brushed aside.

Outside the chamber, whispers began to spread. Journalists caught fragments of his testimony, their pens scratching furiously as they tried to decode the implications. Was this incompetence, or was it deliberate? Had the Ombudsman himself become part of a system designed not to resolve disputes, but to bury them?

For Alan Smith and the other COT members, the realisation was chilling. They had stepped into arbitration believing it was a path to justice. Instead, they had walked into a labyrinth where the rules shifted in the dark, and every turn led deeper into deception. Pinnock’s words were not just testimony — they were evidence of a conspiracy, a glimpse into a treacherous design that reached far beyond the chamber walls.

The Larger Conspiracy

The pattern was becoming clear. Telstra’s faults had been documented, AUSTEL’s draft reports had condemned their conduct, and yet those reports were buried, withheld from the very people who needed them most. Now, years later, the Ombudsman himself admitted that the arbitrator had no control, that the process had slipped into shadows beyond the agreed framework.

It was as if the entire system had been constructed to fail the claimants — to grind them down, to exhaust them, to ensure that the truth never saw daylight. The arbitration was not a mechanism of justice; it was a weapon, wielded against those who dared to challenge the power of a telecommunications giant.

And Pinnock, seated under the Senate lights, was the custodian of that weapon. His testimony was not the language of oversight. It was the language of betrayal. The evidence tampering was real, as the following image shows.

Remember to hover your mouse or cursor over the images as you scroll down the homepage.

The Turning Point

For the COT Cases, this moment became a turning point. The façade of fairness had cracked, revealing the machinery of corruption beneath. The Senate hearing was no longer just an inquiry — it was a stage where the truth flickered briefly before being smothered again.

The victims were left with a haunting question: if the Ombudsman himself admitted that the arbitrator had no control, then who did? Who was pulling the strings, rewriting the rules, and ensuring that justice was never delivered?

The answer lay somewhere in the shadows — in boardrooms, in government offices, in corridors where power moved unseen. And as the claimants left the chamber that day, they knew the battle was no longer about arbitration. It was about exposing a conspiracy that had corrupted the very foundations of justice.

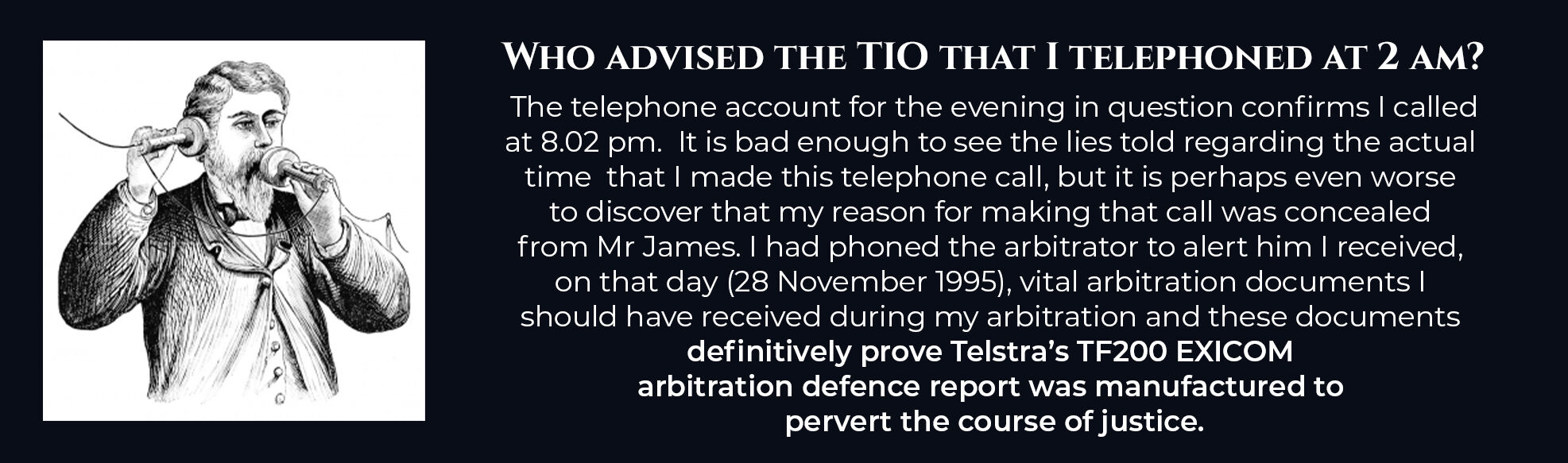

The Aftermath

The fabricated phone call was more than a lie — it was a weapon. And once it was unleashed, the damage was immediate. My reputation was shredded, the investigation halted, and the truth buried beneath layers of deceit.

But betrayal has a way of igniting resolve. For my partner and me, that moment became the beginning of a long, relentless crusade. We refused to accept the narrative written by Pinnock, Hughes, and Rundell. We refused to let their collaboration define the truth.

What followed was not a battle fought in courtrooms alone, but in archives, in letters, in endless nights spent piecing together fragments of evidence. Every document uncovered, every contradiction exposed, became another step in dismantling the façade they had built.

The corridors of power were lined with silence. Institutions turned away, unwilling to confront the corruption in their midst. Yet silence only sharpened our determination. For more than thirty years, we carried the weight of this fight, exposing the truths concealed by their falsehoods, refusing to let the lie stand unchallenged.

A Crusade Against Shadows

It was not just about clearing my name. It was about justice — for the COT Cases, for every claimant who had been betrayed by a system designed to fail them. The fabricated 2:00 AM call was a symbol of how easily truth could be twisted, how reputations could be destroyed with a single stroke of a pen.

We knew the conspiracy went beyond three men. It was systemic, woven into the fabric of institutions that claimed to protect fairness but instead shielded corruption. Each revelation, each document, each testimony became part of a larger mosaic — a picture of betrayal at the highest levels.

Thirty Years of Resistance

The journey has been long, marked by frustration, exhaustion, and moments of despair. But it has also been marked by resilience. We have stood against the silence, against the betrayal, against the machinery of power that sought to erase the truth.

And still, the fight continues. The lie may have been weaponised against me, but the truth remains. It waits in the shadows, demanding to be heard.

Had the government taken these simple steps thirty years ago, there would be no absentjustice.com or my book titled "The Arbitrator," which is set to be released on December 17, 2025Why did Dr Gordon Hughes state in his award at point 3.2 (h) that these problems had been fixed by July 1994, knowing full well that my ongoing billing problems had never been investigated? What sinister motive was behind this lie, and who was controlling what Dr Hughes could or could not investigate in my arbitration?

In a shocking display of corruption, AUSTEL colluded with Telstra, allowing the company to bypass the arbitration process entirely. On October 16, 1995—five months after my arbitration concluded—where the arbitrator had already shamelessly rejected the requests of his consultants for additional time to investigate my persistent phone problems (see Open Letter File No/47-A to 47-D) and (Exhibit 45-c -File No/45-A),

which AUSTEL itself had deemed systemic faults. In a clandestine move, AUSTEL permitted Telstra to address my ongoing billing problems behind closed doors (see 46-L Open letter File No/46-A to 46-l). This underhanded scheme reveals the treacherous nature of these so-called arbitration officials—self-serving, duplicitous, and utterly devoid of integrity.

By facilitating this manoeuvre, AUSTEL condemned me to a fate in which I was denied my legal right to respond to Telstra’s defense to their October 16, 1995 submission (see Absent Justice Part 2 - Chapter 14 - Was it Legal or Illegal? ). This betrayal ensured that Telstra escaped the obligation to prove that my ongoing billing problems had been resolved, even as those issues persisted and tormented me for another nine years after I was forced to sell my business.

The foul residue of their malevolence still permeates the air in 2025, exposing the depths of their insidious corruption.

This harsh reality remained buried for nearly nine years, revealing a disturbing truth about the corruption embedded in Australia’s bureaucratic system—where deceit, concealment, and betrayal are allowed to fester under the guise of authority. The depth of this treachery was not only appalling but evil, driven by an arbitrator who betrayed his duty and my trust, and whose actions went on to destroy the business lives of the new owners of my company (see Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story)

“Hundreds of federal public servants were sacked, demoted or fined in the past year for serious misconduct. Investigations into more than 1000 bureaucrats uncovered bad behaviour such as theft, identity fraud, prying into file, leaking secrets. About 50 were found to have made improper use of inside information or their power and authority for the benefit of themselves, family and friends“

"Beware The Pen Pusher Power - Bureaucrats need to take orders and not take charge”, which noted:“Now that the Prime Minister is considering a wider public service reshuffle in the wake of the foreign affairs department's head, Finances Adamson, becoming the next governor of South Australia, it's time to scrutinise the faceless bureaucrats who are often more powerful in practice than the elected politicians."

"Outside of the Canberra bubble, almost no one knows their names. But take it from me, these people matter."

"When ministers turn over with bewildering rapidity, or are not ‘take charge’ types, department secretaries, and the deputy secretaries below them, can easily become the de facto government of our country."

"Since the start of the 2013, across Labor and now Liberal governments, we’ve had five prime ministers, five treasurers, five attorneys-general, seven defence ministers, six education ministers, four health ministers and six trade Ministers.”

This article was quite alarming. It was disturbing because Peta Credlin, someone with deep knowledge of Parliament House in Canberra, has accurately addressed the issue at hand. I not only relate to the information she presents, but I can also connect it to the many bureaucrats and politicians I have encountered since this ordeal began—before, during, and after my arbitration.

The Treacherous Web of Bureaucratic Power

Bernard Collaery and Timor-Leste

The involvement of Bernard Collaery, former Attorney-General of the ACT, casts a long shadow over the Timor-Leste negotiations. His role, intertwined with Australian bureaucrats, reflects a betrayal of trust and justice. At the heart of this scandal lies the interception of private telephone conversations during critical oil and gas negotiations in the Timor Sea. These resources, rightfully belonging to Timor-Leste, became bargaining chips manipulated by those who cloaked themselves in authority while undermining the sovereignty of a struggling nation.

Bureaucrats as Puppeteers

Peta Credlin’s 2021 article in the Herald Sun exposes the staggering imbalance of power between bureaucrats and ministers. Ministers, stripped of genuine authority, are reduced to puppets manipulated by unelected officials who wield disproportionate influence. This dereliction of duty leaves the public interest vulnerable, as those entrusted to serve instead exploit their positions. The narrative here is not one of governance but of manipulation, in which bureaucrats act as tyrants rather than as servants of democracy.

The COT Cases and the Blockade of Truth

The corruption extends into the COT (Customer-Owned Telecommunications) Cases, where bureaucrats orchestrated a blockade to prevent investigation into ongoing telephone faults. Their calculated interference ensured that arbitrators remained blind to the truth, devastating businesses that sought justice. This deliberate obstruction highlights the insidious nature of bureaucratic power — not only failing to resolve problems but actively ensuring they remain hidden. The result was the destruction of livelihoods, sacrificed at the altar of corporate and bureaucratic interests.

A Chilling Reminder

The COT arbitrations stand as a chilling reminder of how bureaucrats can wield power not as servants of the people, but as tyrants cloaked in respectability. Their actions reveal a system where authority is abused, truth is suppressed, and justice is denied. What emerges is a portrait of governance corrupted from within, where those entrusted with responsibility betray the very citizens they are meant to protect.

Echoes of Betrayal: Wheat Sales to China

The betrayal is not new. Reflecting on Australia’s wheat sales to Communist China in 1967, the hypocrisy becomes clear. Bureaucrats knowingly allowed grain to be repurposed to fuel North Vietnam’s war effort against Australian, New Zealand, and American troops. This act of negligence and complicity demonstrates how detached decision-makers, insulated by theory and bureaucracy, can transform potential solutions into catastrophic consequences. It is a reminder that betrayal often comes not from enemies abroad, but from incompetence at home.

The People's Republic of China

Murdered for Mao: The killings China ‘forgot’

The Letter, the Truth, and the Waiting

In August 1967, I found myself in a situation so precarious, so surreal, that it would etch itself into the marrow of my memory. I was aboard a cargo ship docked in China, surrounded by Red Guards stationed on board twenty-four hours a day, spaced no more than thirty paces apart. After being coerced into writing a confession—declaring myself a U.S. aggressor and a supporter of Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist leader in Taiwan—I was told by the second steward, who handled the ship’s correspondence, that I had about two days before a response to my letter might reach me. That response, whatever it might be, would be delivered by the head of the Red Guards himself.

It was the second steward who quietly suggested I write to my parents. I did. I poured myself into 22 foolscap pages, writing with the urgency of a man who believed he might not live to see the end of the week. I told my church-going parents that I was not the saintly 18-year-old they believed I was. I confessed that the woman they had so often thanked in their letters—believing her to be my landlady or carer—was in fact my lover. She was 42. I was 18 when we met. From 1963 to 1967, she had been my anchor, my warmth, my truth. I wrote about my life at sea, about the chaos and the camaraderie, about the loneliness and the longing. I wrote because I needed them to know who I really was, in case I was executed before I ever saw them again.

As the ship’s cook and duty mess room steward, I had a front-row seat to the daily rhythms of life on board. I often watched the crew eat their meals on deck, plates balanced on the handrails that lined the ship. We were carrying grain to China on humanitarian grounds, and yet, the irony was unbearable—food was being wasted while the people we were meant to help were starving. Sausages, half-eaten steaks, baked potatoes—they’d slip from plates and tumble into the sea. But there were no seagulls to swoop down and claim them. They’d been eaten too. The food floated aimlessly, untouched even by fish, which had grown scarce in the harbour. Starvation wasn’t a concept. It was a presence. It was in the eyes of the Red Guards who watched us eat. It was in the silence that followed every wasted bite.

A Tray of Leftovers and a Silent Exchange

After my arrest, I was placed under house arrest aboard the ship. One day, I took a small metal tray from the galley and filled it—not with scraps, but with decent leftovers. Food that would have gone into the stockpot or been turned into dry hash cakes. I walked it out to the deck, placed it on one of the long benches, patted my stomach as if I’d eaten my fill, and walked away without a word.

Ten minutes later, I returned. The tray had been licked clean.

At the next meal, I did it again—this time with enough food for three or four Red Guards. I placed the tray on the bench and left. No words. No eye contact. Just food. I repeated this quiet ritual for two more days, all while waiting for the response to my letter. During that time, something shifted. The Red Guard, who had been waking me every hour to check if I was sleeping, stopped coming. The tension in the air thinned, just slightly. And I kept bringing food—whenever the crew was busy unloading wheat with grappling hooks wrapped in chicken wire, I’d slip out with another tray.

To this day, I don’t know what saved me. It was certainly not the letter declaring myself a U.S. aggressor and a supporter of Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist leader in Taiwan. Maybe it was luck. Or perhaps it was that tray of food, offered without expectation, without speech, without condition. A silent gesture that said, “I see you. I know you’re hungry. I know you’re human.”

And maybe, just maybe, that was enough. British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smith's Seaman.

“On some significant issues, the Australian Parliament has ceased to be a place of effective lawmaking by the people, for the people”"It has become commonplace for Parliamentarians to see a marathon supernuanced career out with ideals sacrificed for ambition"

• Who were the government bureaucrats who condoned the bugging during the COT arbitrations?• Were they the same individuals—or perhaps their successors—who approved the bugging of Timor-Leste’s offices?

Exposing the truth meant I faced a possible jail term.

It may be unsettling to confront, but in August 2001 and again in December 2004, the Australian Government issued chilling written threats (see Senate Evidence File No 12) warning me of potential contempt charges if I even dared to reveal the sinister contents of the in-camera Hansard records from July 6 and 9, 1998. These records lay bare a dark conspiracy: that ignoring the five COT cases under investigation by the Senate Committee, while leaving the remaining sixteen unresolved, would be a gross injustice against the ignored claimants. This damning observation came from none other than Senator Chris Schacht from South Australia, who stated on 9 July 1998, when addressing Telstra's arbitration liaison office in charge of downgrading my arbitration claims,

Senator SCHACHT speakes to Telstra's arbitration defence officer - Mr B------n, "I agree with the chair. We have a difficulty. In many senses, we all say, 'For God's sake. Telstra just give the last four all half a million or a million dollars each and stip it immediately.' But that would be an injustice to the 16 or whatever you have settled"

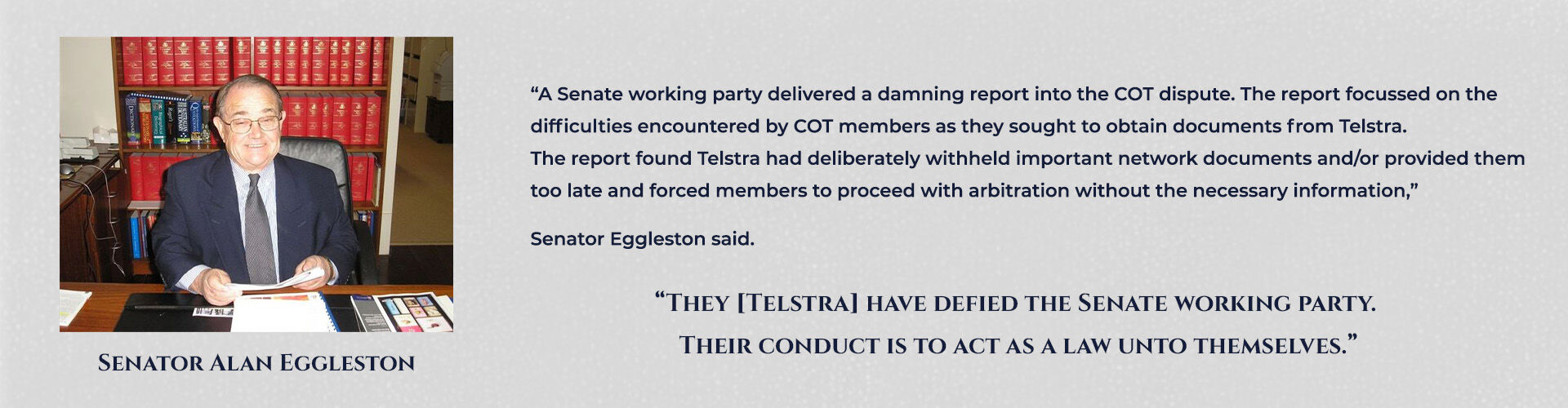

Senator Schacht revealed the troubling realities behind four COT cases involving Ann Garms, Ralph Bova, Ross Plowman, Anthony Honor, and Graham Schorer. Instead of the meagre sums of $500,000 or $1 million each initially suggested, these individuals were shockingly awarded over $18 million in punitive damages between them. This immense figure ballooned after the damning report dated January 7, 1999, from Scandrett & Associates to Senator Ron Boswell (referenced in Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13). The report laid bare a web of deep-seated corruption, exposing the alarming truth that communications regarding the COT Cases arbitration—fax exchanges among lawyers, accountants, and technical consultants—were being sinisterly intercepted and manipulated by Telstra before they reached their intended destinations. The statements provided by those who prepared this critical report for the Senate reveal the treachery and deceit lurking behind the facade of legal proceedings.

“We canvassed examples, which we are advised are a representative group, of this phenomena .

“They show that

- the header strip of various faxes is being altered

- the header strip of various faxes was changed or semi overwritten.

- In all cases the replacement header type is the same.

- The sending parties all have a common interest and that is COT.

- Some faxes have originated from organisations such as the Commonwealth Ombudsman office.

- The modified type face of the header could not have been generated by the large number of machines canvassed, making it foreign to any of the sending services.”

One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this 7 January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

When the government became aware that Telstra had been screening and potentially altering documents related to the arbitration of the COT Cases before re-faxing them to their designated recipients, it raised serious concerns about Telstra's interference with the due process of law. This interference was significant enough that the government feared the resulting report (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) could be so damaging that its public release might derail Telstra's ongoing privatisation efforts.

Australian Senate Hansard, see Senate – Parliament of Australia page 125 records Senator Schacht stating:

I ask Telstra: a document that has been colloquially called the ‘pink herring’, that was filed with the US Securities Exchange recently, focused on the adverse publicity of the CoT cases. The document was prepared as part of the privatisation and so on. It focuses more on the effect of the publicity on Telstra, apparently than on the materiality of any sums of money which may ultimately be paid. Will the Australian prospectus for the Telstra sale give a more detailed assessment of the financial effect of the CoT cases on Telstra?. (Chapter 6 - US Securities Exchange - pink herring).

Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1

The AFP believed Telstra was deleting evidence at my expense.

During my first meetings with the AFP, I provided Superintendent Detective Sergeant Jeff Penrose with two Australian newspaper articles concerning two separate telephone conversations with The Hon. Malcolm Fraser, a former Prime Minister of Australia. Mr Fraser reported to the media only what he thought was necessary concerning our telephone conversation, as recorded below:

“FORMER prime minister Malcolm Fraser yesterday demanded Telecom explain why his name appears in a restricted internal memo.

“Mr Fraser’s request follows the release of a damning government report this week which criticised Telecom for recording conversations without customer permission.

“Mr Fraser said Mr Alan Smith, of the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp near Portland, phoned him early last year seeking advice on a long-running dispute with Telecom which Mr Fraser could not help.”

Senate Hansard dated June 1997 (refer to pages 76 and 77 - Senate - Parliament of Australia Senator Kim Carr states to Telstra’s primary arbitration defence Counsel (Re: Alan Smith:

Senator CARR – “In terms of the cases outstanding, do you still treat people the way that Mr Smith appears to have been treated? Mr Smith claims that, amongst documents returned to him after an FOI request, a discovery was a newspaper clipping reporting upon prosecution in the local magistrate’s court against him for assault. I just wonder what relevance that has. He makes the claim that a newspaper clipping relating to events in the Portland magistrate’s court was part of your files on him”. …

Senator SHACHT – “It does seem odd if someone is collecting files. … It seems that someone thinks that is a useful thing to keep in a file that maybe at some stage can be used against him”.

Senator CARR – “Mr Ward, we have been through this before in regard to the intelligence networks that Telstra has established. Do you use your internal intelligence networks in these CoT cases?”

The most alarming situation regarding the intelligence networks that Telstra has established in Australia is who within the Telstra Corporation has the necessary expertise, i.e., government clearance, to filter the raw information collected before it is impartially catalogued for future use? How much confidential information concerning the telephone conversations I had with the former Prime Minister of Australia in April 1993 and again in April 1994, regarding Telstra officials, holds my Red Communist China episode, which I discussed with Fraser?

More importantly, when Telstra was fully privatised in 2005, which organisation in Australia was given the charter to archive this sensitive material that Telstra had been collecting about their customers for decades?

PLEASE NOTE:

At the time of my altercation referred to in the above 24 June 1997 Senate - Parliament of Australia, my bankers had already lost patience and sent the Sheriff to ensure I stayed on my knees. I threw no punches during this altercation with the Sheriff, who was about to remove catering equipment from my property, which I needed to keep trading. I actually placed a wrestling hold, ‘Full Nelson’, on this man and walked him out of my office. All charges were dropped by the Magistrates' Court on appeal when it became evident that this story had two sides.

The Canadian government’s handling of the Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) Cape Bridgewater telephone exchange report reveals a chilling, troubling narrative—one intricately woven into a sinister tapestry of deceit and manipulation. In Australia, I witnessed key stakeholders—government officials, legal representatives, and those overseeing the arbitration process—demonstrate a blatant apathy toward pursuing the truth. Their indifference cultivated an insidious culture of corruption that thrived in the shadows.

A Web of Betrayal and Corruption

Let me take you back to the moment when everything began to unravel. Just before the Canadian team arrived, Lane orchestrated a pre-investigation that would prove devastating. During the fraught COT arbitration, Ericsson quietly acquired Lane for an undisclosed sum. Imagine that: the very company under scrutiny suddenly owned the investigator. From that moment, the integrity of the process was poisoned.

Canadian authorities, meanwhile, chose to remain blind. They knew that if my claims against Bell Canada International were substantiated, it would expose serious flaws in their own telecommunications infrastructure. Such revelations would tarnish the reputations of firms they celebrated as technological leaders. Protecting prestige mattered more than defending truth.

DMR Group Canada Inc., tasked with overseeing Lane’s findings, delayed for eighteen months before finally signing off on a report in August 1997. By then, Lane had been absorbed into Ericsson, erased from the record. What arrived bore only DMR’s signature—a betrayal of transparency and trust.

Evidence of Corruption

The trail of documents tells its own story. On March 9, 1995, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman confirmed that DMR Group Canada was Lane’s principal technical advisor. Yet by April 7, 1995, Lane had already submitted draft findings based on just eleven per cent of my claim material. My meticulously compiled chronology of events—prepared by two senior detective sergeants from the Queensland Police for $56,000—vanished without explanation.

Then came the damning admission. On April 18, 1995, Arbitration Project Manager John Rundell wrote:

“Any technical report prepared in draft by Lanes will be signed off and appear on the letter of DMR Inc.” (see Prologue Evidence File No 22-A)

That single sentence revealed the corruption at the heart of the arbitration.

When I asked why neither investigator had signed off on the report, Paul Howell from DMR Group Canada and David Reid from Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd (Australia), the arbitrator, Dr Hughes, rejected my request in two telephone calls and in his letter dated 5 May 1995, noting:

“I refer to your telephone message of 4 May and your facsimiles of 4 and 5 May 1995 and advise I do not consider grounds exist for the introduction of new evidence or the convening of a hearing at this stage.”

And he reiterated his previous instructions:

“...any comments regarding the factual content of the Resource Unit reports must be received … by 5.00 p.m. on Tuesday 9 May 1995″. (see Arbitrator File No/48)

It was not until August 1996 that I finally received Paul Howell’s signature from DMR Canada—over a year later. By then, Lane’s report had been prepared long before DMR even established its presence in Australia.

The conclusion is inescapable: the process was riddled with deception as Telstra's Falsified BCI Report 2 shows. Ericsson absorbed Lane while Ericsson’s equipment was under scrutiny. To this day, I remain deprived of essential Ericsson claim documents—documents that, by agreement, should have been returned within six weeks of the arbitration’s conclusion. Yet here I stand in 2025, still fighting.

• Suppression of evidence: Telstra arbitration documents, Horizon software bugs, Robodebt warnings.• Institutional survival over human lives: Wheat trade profits, Telstra’s inflated value, Robodebt’s defence. Letters from KPMG.• Government complicity: Both the British and Australian governments had vested interests in protecting corporations, even at the expense of ordinary citizens.

• Expose the betrayal.• Demand accountability.• Break the cycle of bureaucratic deceit.

Absentjustice.com and The Arbiitraitor serve as platforms to connect these dots, showing Australians that betrayal is not random—it is systemic and must be confronted.

Absentjustice.com and The Arbiitraitor serve as platforms to connect these dots, showing Australians that betrayal is not random—it is systemic and must be confronted.Don't forget to hover your mouse/cursor over the kangaroo image to the right of this page → → →

It is crucial to emphasise the significance of the four letters dated 17 August 2017, 6 October 2017, 9 October 2017, and 10 October 2017, authored by COT Case Ann Garms shortly before her passing. These letters were addressed to The Hon. Malcolm Turnbull MP, Prime Minister of Australia, and Senator the Hon. Mathias Cormann (See File Ann Garms 104 Document). These letters state that Gaslighting methods were used against the COT Cases to destroy our legitimate claims against Telstra. (rb.gy/dsvidd).

Psychological manipulation

Gaslighting is a form of psychological manipulation in which the abuser attempts to sow self-doubt and confusion in the victim's mind, i.e., you do not have a telephone problem. Our records show you are the only customer complaining, even though the documents indicate the situation is systemic. Typically, gaslighting methods are used to seek power and control over the other person by distorting reality and forcing them to question their judgment and intuition.

Within the halls of both State and Federal Parliament, betrayal runs rampant. Colleagues are not merely undermined but systematically destroyed—their lives shattered in the relentless pursuit of power through malicious falsehoods. The COT Cases peeled back the layers of this insidious system, revealing treachery that may have only intensified.

An arbitrator, ostensibly charged with oversight, instead ignored the devastating implications—ruling that the faults I faced bore no impact on the viability of my business. This was not a lapse; it was a calculated move in a web of corruption. As the narrative unfolds on absentjustice.com, the truth proves far more sinister than it appears, and the consequences of their deceit are catastrophic.

Two significant documents in this briefcase, dated between July and December 1992, reveal a troubling pattern of deception and misinformation related to my ongoing telephone complaints. These documents, now formalised under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act, highlight that I was consistently misled about the quality and reliability of my service for several years leading up to my visit on June 3, 1993.

Telstra senior management finally visited my business, a five-hour drive from Melbourne. Within five minutes of saying hello, Mr Smith, I knew I was in for another round of untruths.

I should have known better. It was just another case of 'No fault found.' We spent some considerable time 'dancing around' a summary of my phone problems. Their best advice for me was to continue doing exactly what I had been doing since 1989: keeping a record of all my phone faults. I could have wept. Finally, they left.

A little while later, in my office, I found that Aladdin had left behind his treasures: the Briefcase Saga was about to unfold.

Aladdin

The briefcase was not locked, and I opened it to find out it belonged to Mr Macintosh. There was no phone number, so I had to wait for business hours the next day to track him down. However, what was in the briefcase was a file titled 'SMITH, CAPE BRIDGEWATER'. After five gruelling years fighting the evasive monolith of Telstra, being told various lies along the way, here was possibly the truth, from an inside perspective.

One critical document not seen before stated:

“Our local technicians believe that Mr Smith is correct in raising complaints about incoming callers to his number receiving a Recorded Voice Announcement saying that the number is disconnected.

“They believe that it is a problem that is occurring in increasing numbers as more and more customers are connected to AXE.” (See False Witness Statement File No 3-A)

To further support my claims that Telstra already knew how severe my Ericsson Portland AXE telephone faults were, can best be viewed by reading Folios C04006, C04007 and C04008, headed TELECOM SECRET (see Front Page Part Two 2-B), which states:

“Legal position – Mr Smith’s service problems were network related and spanned a period of 3-4 years. Hence Telecom’s position of legal liability was covered by a number of different acts and regulations. … In my opinion Alan Smith’s case was not a good one to test Section 8 for any previous immunities – given his evidence and claims. I do not believe it would be in Telecom’s interest to have this case go to court.

“Overall, Mr Smith’s telephone service had suffered from a poor grade of network performance over a period of several years; with some difficulty to detect exchange problems in the last 8 months.”

This visit by these two Telstra executives not only marked a pivotal moment but also initiated a complex and convoluted saga involving a briefcase that has come to symbolise my struggles. However, the issues at hand run much deeper than a casual glance at the homepage might suggest. The more one delves into the intricate details of my experience, the more apparent the severity of the situation becomes. It is not merely about unsatisfactory service; it reflects a systematic failure in communication and accountability on the part of the service provider, leaving me to grapple with the consequences for an extended period. Understanding this context is crucial to fully grasping the challenges I face

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government held an iron grip over the nation’s telephone network through its communications carrier, Telecom, now privatised and renamed Telstra. This monopoly wielded its power with a merciless disregard for our needs, allowing the network to rot and crumble, leaving us vulnerable and disconnected.When four small business owners, including myself, found ourselves ensnared by a web of catastrophic communication failures, we were lured into a treacherous trap set by the Federal Government. They promised us a commercial assessment process they claimed to endorse, but what unfolded was an elaborate sham. The appointed arbitrator was nothing more than a puppet, dancing to Telstra’s sinister tune, manipulating the process to suffocate our claims and bury their heinous acts beneath a facade of legitimacy.Unfortunately, none of the ongoing telephone issues that led me to arbitration in the first place were ever investigated. As a result, these problems continued to disrupt my business for another six years after the arbitration, as the following narrative will illustrate.

A secret government investigation into my seven years of complaints about ongoing telephone faults revealed, in its 2 to 212-point report, that Telstra had breached its licensing conditions. Consequently, my complaints raised during my government-endorsed arbitration were deemed valid. However, this 68-page report was provided only to Telstra to aid in its defence of my arbitration claims, while it was withheld from both the arbitrator and me.

I ask every reader visiting absentjustice.com to please download this file → (AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) and read it for themselves how this one document proved my claims before I was even forced into arbitration under the guise that the process would fix my ongoing telephone problems, which turned out to be the biggest lie of the whole sorry saga.

The COT Cases never had a chance.

On July 4, 1994, (Exhibit 45-c -File No/45-A), I confronted serious threats articulated by Paul Rumble, a Telstra representative on the arbitration defence team. Disturbingly, he had been covertly furnished with some of my interim claims documents by the arbitrator—a breach of protocol that occurred five months before the arbitrator should have proved this information. Given the gravity of the situation, my response needed to be exceptionally meticulous. It was at this early stage of my arbitration, less than three months in, that Dr Hughes had already broken the arbitration agreement rules. In this correspondence, I made it unequivocally clear:

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no intention of submitting any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call I received from Steve Black, another arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, Black issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions he and Mr Rumble gave, I would jeopardise my access to crucial documents and risk ongoing problems with my telephone service.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood that there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could affect the arbitrator's decision in my case.

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on 26 September 1994. During this visit, they began asking probing questions about my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

Threats carried out

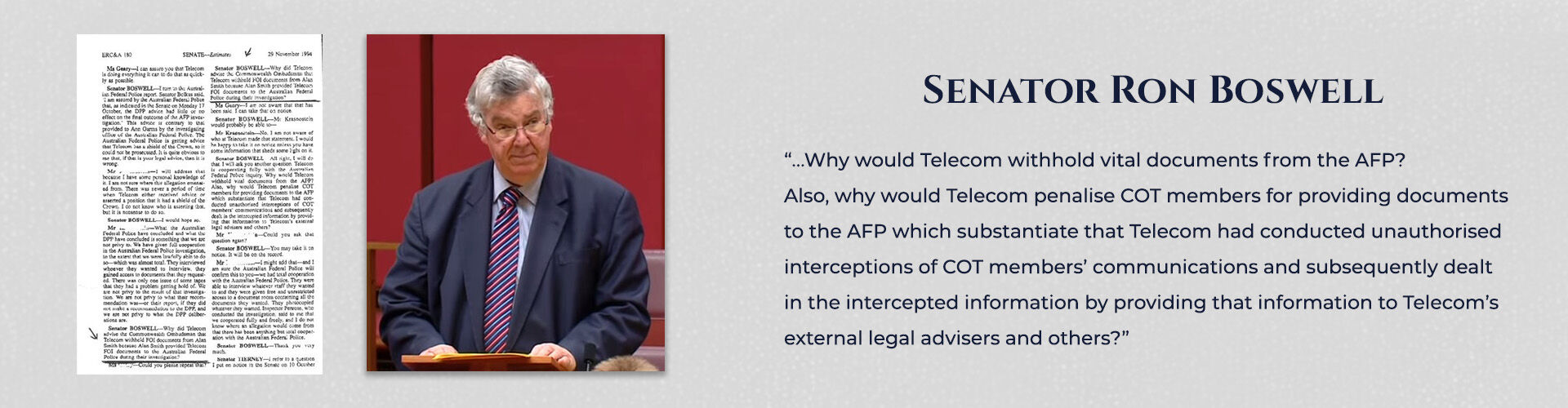

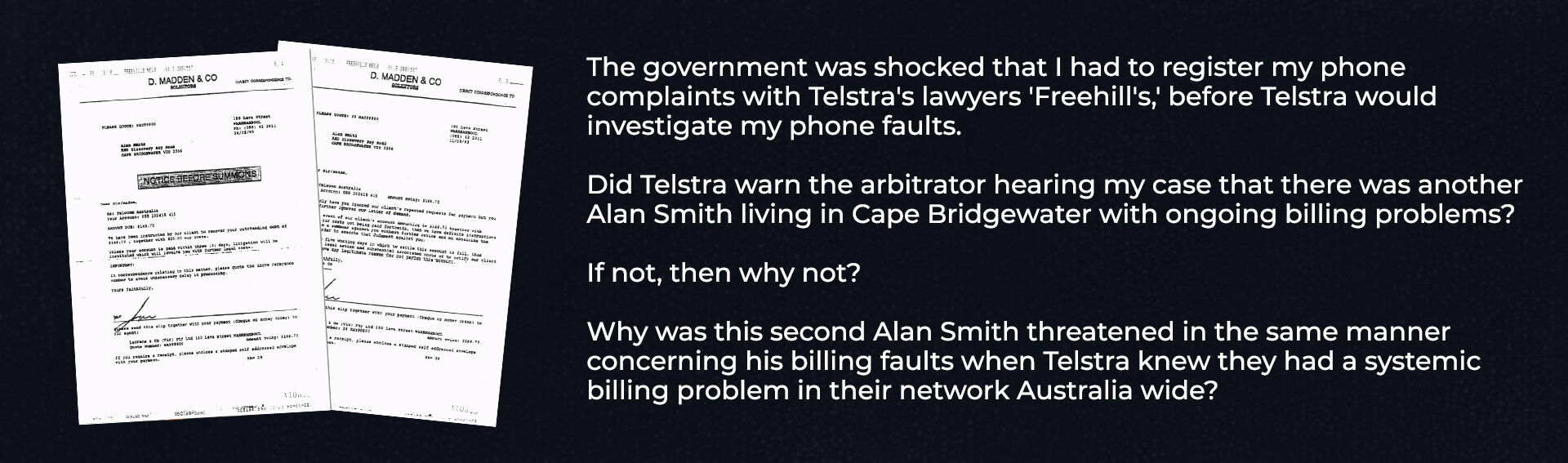

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

Thus, the Threats Became a Reality

What is so appalling about this withholding of relevant documents is this: no one in the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman (TIO) office or the government has ever investigated the disastrous impact of this withholding on my overall submission to the arbitrator. The arbitrator and the government (at the time, Telstra was a government-owned entity) should have initiated an investigation into why an Australian citizen who had assisted the AFP in its investigations into unlawful interception of telephone conversations was so severely disadvantaged in a civil arbitration.

Why did Dr Hughes, the government-appointed arbitrator, fail to report these threats to the Supreme Court of Victoria, under whose auspices the arbitration was conducted, especially after Telstra implemented these threats

In January 2019, after leaving our cherished Cape Bridgewater holiday camp and guest house, my partner Cathy and I drove along Cape Bridgewater Road. This 16-kilometre stretch leads up a slight hill as we said goodbye to Portland. As we looked up, we saw a massive Telstra billboard towering above us. Its bold letters announced that Cape Bridgewater would finally receive the reliable service we had long been denied. However, despite the sign standing tall and triumphant, to me, it felt like a cruel reminder of what we had lost

The above billboard wording: “…We’ve expanded Australia’s best network to Cape Bridgewater” felt like a mockery of our departure, taunting us with what could have been. It was not just an advertisement; it became a symbol of betrayal, a reminder that while we had been neglected and broken by a failing system, others would now benefit from the service that could have saved us. That hill and that sign became the final punctuation mark in a story of loss and injustice, seared into my memory as the moment when hope transformed into bitter truth.

The sting was immediate—like salt rubbed into a raw wound. After decades of silence on the line, watching our business collapse, and selling everything for little more than the land beneath it, here was Telstra’s belated promise, thirty-six years too late.

⚖️ Call for Justice

My name is Alan Smith, and this is the story of my battle with a telecommunications giant and the Australian Government. Since 1992, this battle has unfolded through various institutions, including elected governments, government departments, regulatory bodies, the judiciary, and the telecommunications behemoth Telstra—or Telecom, as it was known at the time this story began. The quest for justice continues to this day.

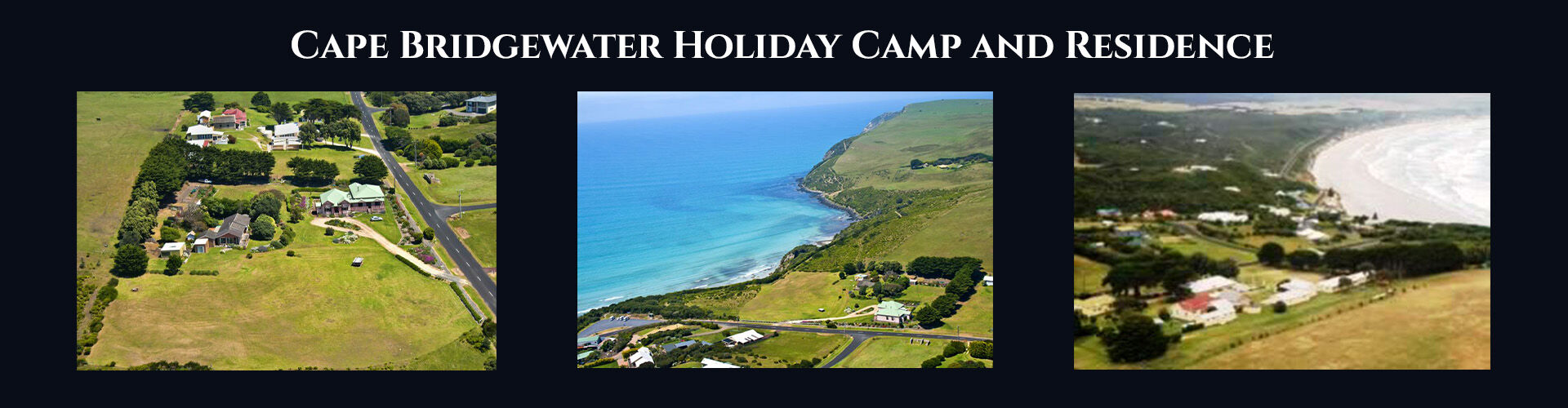

My story began in 1987, when I decided that my life at sea—where I had spent the previous 20 years—was over. I needed a new, land-based occupation to carry me through to retirement and beyond. Of all the places I had visited around the world, I chose to make Australia my home.

Hospitality was my calling, and I had always dreamed of running a school holiday camp. So imagine my delight when I saw the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Convention Centre advertised for sale in The Age. Nestled in rural Victoria, near the small maritime port of Portland, it seemed perfect. I conducted what I believed was thorough due diligence to ensure the business was sound—or at least, all the due diligence I was aware of at the time. Who would have thought I needed to check whether the phones worked?

Within a week of taking over the business, I knew I had a problem. Customers and suppliers were telling me they had tried to call but couldn’t get through. That’s right—I had a business to run, but the phone service was, at best, unreliable, and at worst, completely absent. Naturally, we lost business as a result.

The Camp was profoundly reliant on phone communication. It was our vital link to city dwellers eager to connect with our services. One of our most significant oversights—blinded by the charm of this coastal haven—was failing to investigate the existing telephone system. At the time, mobile coverage was virtually nonexistent, and business was conducted through traditional means—not online, and certainly not by email.

We soon discovered we were tethered to an antiquated telephone exchange, installed more than 30 years earlier and designed specifically for 'low-call-rate' areas. This outdated, unstaffed exchange had a pitiful capacity of just eight lines.

• My fight began simply: to secure a working phone service.• Despite compensation promises, the faults persisted. I sold my business in 2002, but the new owners suffered the same fate.• Other small business owners joined me—we became known as the Casualties of Telecom.• All we ever asked: acknowledgement, repair, and fair compensation. A working phone—was that too much?

During a typical week, the picturesque Cape Bridgewater was home to 66 residential families—not including those who used their coastal retreats to escape the bustle of city life. This created a significant challenge, especially considering many of these families had children.

The eight service lines struggled to support a growing census of 130 adults and children. By the time a modern Remote Control Module (RCM) was finally installed in August 1991, twelve children had been added to the mix, bringing the total population to 144. However, various weekend visitors often brought that figure to 150 or more.

The Hidden Cost of Cape Bridgewater’s Failing Lines

No wonder I was financially broken by the end of 1988—barely a year after taking over the business in late 1987. The reality was brutal: Cape Bridgewater’s telecommunications setup was catastrophically inadequate.

In stark terms, if just four of the 144 residences were making or receiving calls, only four lines remained for the other 140 residents. That’s not just poor planning—it’s a systemic failure. My business was strangled by a network that couldn’t support even the most basic communication needs. Every missed call was a missed opportunity. Every dropped connection was another nail in the coffin of a venture I had poured everything into.

We stepped into this complex landscape of limited connectivity and coastal beauty with ambition and optimism. The Camp was more than a business—it was a dream made real. A serene retreat where the stress of city life could dissolve into the ocean mist. However, as we quickly learned, dreams require infrastructure to thrive.

Our phone lines became both our lifeline and our most significant obstacle. Booking inquiries, supply orders, emergency calls—even simple conversations with clients—all had to pass through those eight fragile channels. During peak times, the lines were constantly engaged. Guests complained they couldn’t reach us. Suppliers missed confirmations. Opportunities slipped through our fingers like sand.

A Conspiracy of Silence: The Betrayal Behind the Arbitration

The document from March 1994 (AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) reveals a troubling reality: government officials tasked with investigating my ongoing telephone issues found my claims against Telstra to be valid. This was not merely an oversight; it indicates a deliberate pattern of misconduct that played out between Points 2 and 212.

It is chilling to consider that, had the arbitrator been furnished with this critical evidence, he would likely have awarded me far greater compensation for my substantial business losses. Instead, my claims were weakened because they lacked a proper log over the six-year period that AUSTEL deceptively used to formulate their findings, as outlined in AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings.

The Arbitrator & the Corruption of Arbitration in Australia

Introduction: A System Built on Betrayal

The arbitration system in Australia was sold to us as fair, transparent, and government-endorsed. In reality, it was anything but. The Institute of Arbitrators and Mediators Australia (IAMA) was supposed to be independent, yet time and again it bent to political and corporate influence. What should have been a safeguard for justice became a weapon of betrayal.

The COT Cases: Cracks in the System (1990s)

Back in the 1990s, the Casualties of Telstra (COT) cases exposed the rot. Telstra and government officials withheld documents, misled arbitrators, and left claimants fighting blind. Arbitrators ignored evidence that should have been central to their rulings. The result? Ordinary Australians were systematically disadvantaged while Telstra and its allies walked away untouched. Those cases proved one thing: when corporate power colludes with political silence, justice collapses.

The Telstra Briefcase Incident (1992–1993)

I saw this corruption firsthand. Two Telstra executives left an unlocked briefcase in my Cape Bridgewater office. Inside were documents that revealed Telstra’s board and management were orchestrating a campaign to mislead the public. They knew their copper wire network and Ericsson equipment were faulty. Overseas, this equipment was being ripped out of exchanges. Here in Australia, Telstra kept rolling it out, putting vulnerable customers at risk.

When I raised these issues, the arbitrator ruled that the faults had no impact on my business viability. That wasn’t negligence—it was complicity. Later, documents dated July–December 1992, formalised under the Freedom of Information Act, confirmed what I already knew: I had been deliberately misled about the reliability of my service for years.

Continuity of Corruption: 2020–2025

Some people like to believe this corruption was confined to the past, resolved in the 1990s. They’re wrong. Between 2020 and 2025, the same practices continued: altered court documents, perjury, and even allegations of criminal activity within government ranks. In both State and Federal Parliament, betrayal runs rampant. Colleagues are destroyed through malicious falsehoods, just as claimants were destroyed during the arbitrations. The corruption didn’t end—it mutated.

The Human Cost

This wasn’t just about faulty equipment. It was about lives. My business was dismissed, my credibility undermined, and my livelihood jeopardised. Customers were left exposed to dangerous infrastructure while Telstra and government officials escaped accountability. The human cost of this betrayal is immeasurable.

Conclusion: The Arbiitraitor’s Legacy

The arbitration system failed because it was never truly independent. It was corrupted by political and corporate influence from the start. The COT Cases peeled back the layers, but the treachery has only deepened since. My role now is to document the truth, to ensure these betrayals are not forgotten, and to empower others to challenge the silence.

Reflections on Democracy and Accountability

My struggle was never just about me. It was about whether democratic systems can be trusted to uphold transparency, fairness, and accountability.

Canada’s handling of the Cape Bridgewater report, and Australia’s willingness to allow witnesses to be compromised, revealed a disturbing truth: when powerful interests are threatened, the rule of law bends. It delays. It ignores.

So I ask you, my readers, to consider this: do we truly live under systems that protect the vulnerable and hold the powerful to account? Or are we expected to accept corruption disguised as process, silence masquerading as resolution?

For me, the answer is clear. The COT arbitrations were neither transparent nor unbiased. They were riddled with sinister machinations. And while I continue to fight for the return of my rightful documents, I also fight for something larger: the principle that truth must never be buried, and that democracy cannot survive if corruption is allowed to flourish unchallenged.

A Legacy and a Warning

As of 2025, John Rundell still manipulates the arbitration centres in Melbourne and Hong Kong, all while sheltering under the glaring shadow of his own alarming admission: “Any technical report prepared in draft by Lanes will be signed off and appear on the letterhead of DMR Inc.” This chilling confession raises profound doubts about the integrity of the entire arbitration process.

This is the very same Lane Telecommunications (Australia) Pty Ltd that willingly sold its soul, a company embroiled in moral decay. On April 6, 1995, at my business premises, David Reid of Lane and Telstra's Peter Gamble engaged in a covert operation, a series of arbitration tests on my telephone service lines that felt more like a playground for deception than a legitimate examination. Their presence was anything but innocent; it was a calculated move to bury my legitimate claims.

Peter Gamble is infamous for being named by Lindsay White, a brave Telstra whistleblower, during testimony before a Senate Committee. White explicitly warned the Senate that Peter Gamble had named me as one of the five COT Cases who had to be “stopped at all costs” from substantiating our arbitration claims, as shown between pages 36 and 39 of the Senate - Parliament of Australia, dated 24 June 1997.

The stakes couldn’t have been higher.

On that treacherous day, 6 April 1995, during the nominated day for testing my telephone lines, Peter Gamble refused to conduct the essential tests on my phone service, standing alongside David Reid in an act that spoke volumes of their collusion. This blatant refusal came just before Lane disgracefully aligned itself with Ericsson, raising red flags about their intentions. They knew full well that if they tested the Ericsson telephone service that day, it would have exposed the hollow foundation of their deceit and validated my long-standing complaints about insidious telephone issues—real troubles that they were determined to label as mere fabrications.

To further entrench this web of corruption, Dr Gordon Hughes, when confronted by Laurie James, President of The Institute of Arbitrators Australia, about the shocking lack of testing, chose a treacherous path of deceit. His calculated lies, as told in his letter to Laurie James (see Chapter 3 - The Sixth Damning Letter → (Open letter File No/45-G concerning Telstra and David Reid's visit to my business.

My letter, attached to Senator Gareth Evans (see Open Letter File No/49), speaks for itself.

This misleading information ensured that crucial evidence was buried deep, preventing my claims of 'ongoing telephone problems' from seeing the light of day.

It is crucial to reference again the link titled Open letter dated September 25, 2025 → 'the first remedy pursued”, which will be explored in greater detail later in the narrative. By mentioning this link at the outset, visitors to absentjustice.com gain a clear understanding of its significance and its role in the broader story.

This context sets the stage for examining how three individuals—Dr. Hughes, John Pinnock, and John Rundell collaborated to undermine my character. In a single devastating act, they not only tarnished my reputation but also halted a critical investigation by the Institute of Arbitrators Australia. That investigation was intended to assess the validity of my claims, which were substantive and warranted a thorough examination.

Dr Hughes claimed that he and the President of The Institute of Arbitrators Australia had worked on the draft of the arbitration agreement, and that both he and Mr Frank Shelton would ensure our arbitration was conducted under the framework of the Victorian Commercial Arbitration Act 1984. We requested confirmation of this agreement because not only was Frank Shelton the President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, but he was also the TIO Legal Arbitration Counsel, who sought to be exonerated from all liability for drafting the arbitration agreement.

We obtained a copy of the letter dated January 24, 1994, from Frank Shelton to Dr Hughes, communicated through his partnership's head office at Hunt & Hunt (see attached as File 622 point 2 in that letter - AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647). This document clearly shows Frank Shelton advising Dr Hughes that:

" We discussed whether or not the Procedure should come within the ambit of the Victorian Commercial Arbitration Act 1984. We decided that it should.

The situation surrounding clause 24 in our arbitration agreement, which exonerated the author, Frank Shelton, is concerning. Even more troubling is that before my arbitration concluded on May 11, 1995, Frank Shelton became a judge at the Victorian County Court, a position he held for over a decade. This further highlights the lack of justice for the COT cases, who placed their trust in an arbitration process over which the arbitrator had no control.

Pressure from the Senate

Under mounting pressure from the Senate, John Pinnock, the second Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), found himself cornered into making a shocking confession on September 26, 1997. This confession emerged two years after the majority of the COT Cases arbitrations had concluded, reflecting a system rife with corruption and treachery. During this time, the claimants—who had fought tirelessly against an oppressive bureaucracy—had exhausted all their options and were left with no means to challenge the unjust arbitration decisions issued against them. The entire ordeal unfolded like a dark saga of betrayal, as the claimants were systematically deprived of their rights, refer to page 99 of the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D), that:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

It is crucial to highlight the bribery and corruption issues raised by the US Department of Justice against the same Ericsson of Sweden, as reported in the Australian media on 19 December 2019.

One of Telstra's key partners in the building out of their 5G network in Australia is set to fork out over $1.4 billion after the US Department of Justice accused them of bribery and corruption on a massive scale and over a long period of time.

Sweden's telecoms giant Ericsson has agreed to pay more than $1.4 billion following an extensive investigation which saw the Telstra-linked Company 'admitting to a years-long campaign of corruption in five countries to solidify its grip on telecommunications business. (https://www.channelnews.com.au/key-telstra-5g-partner-admits-to-bribery-corruption/)

To this day, I have never received the critical reports on Ericsson’s exchange equipment—painstakingly compiled by my trusted technical consultant, George Close. These documents were the backbone of my case. Their disappearance is a blatant violation of the arbitration rules, which require all submitted materials to be returned to the claimant within six weeks of the arbitrator’s award.

The following letter, dated 16 July 1997, was written by John Pinnock, the official administrator of the arbitrations, to William Hunt and the lawyer to Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson). In this letter, Mr Pinnock notes that.

“Lane is presently involved in arbitrations between Telstra and Bova, Dawson, Plowman and Schorer. The change of ownership of Lane is of concern in relation to Lane’s ongoing role in these arbitrations.

“The first area of concern is that some of the equipment under examination in the arbitrations is provided by Ericsson.…

“The second area of concern is that Ericsson has a pecuniary interest in Telstra. Ericsson makes a large percentage of its equipment sales to Telstra which is one of its major clients.

“It is my view that Ericsson’s ownership of Lane puts Lane in a position of potential conflict of interest should it continue to act as Technical Advisor to the Resource Unit. …

“The effect of a potential conflict of interest is that Lane should cease to act as the Technical Advisor with effect from a date shall be determined.” (See File 296-A - GS-CAV Exhibit 258 to 323)

None of the COT Cases were granted leave to appeal their arbitration awards, even though it is now apparent that the purchase of the Australian government-appointed technical unit Lane had to have been in motion months before the purchase. The government should investigate each COT Case to determine what was lost due to Lane's failure to address the ongoing Ericsson AXE telephone problems, which continued to destroy the businesses of COT cases after the conclusion of their arbitrations.

More than a decade after cunningly embedding itself within the Australian arbitration system and seizing control of Lane, Ericsson now stands accused of colluding with terrorist organisations. This alarming betrayal reeks of corruption as the Australian government inexplicably chooses to ignore the treachery unfolding in plain sight. The interests of countless honest, hardworking small business operators across the nation have been jeopardised, all while those in power turn a blind eye to the dark dealings that threaten the fabric of our society.

What legal basis did John Pinnock, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, have to allow some COT cases to amend their arbitration claims? This decision seems questionable, especially given that Ericsson has a conflict of interest with Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd, which was tasked with assessing the faulty Ericsson equipment that serviced all the businesses involved in the COT cases.

Moreover, what about the other five COT cases whose arbitrations were declared concluded, given that it was Lane who assessed the Ericsson faults associated with those cases? Just because the claims for the five COT cases referenced in Jon Pinnock's letter had not yet been finalised does not justify Mr Pinnock taking sides in determining who receives justice and who does not.

BCI and SVT reports - Section One

Who hijacked the BCI and SVT Reports

It is important to note that during this second AAT hearing (No 2010/4634), Mr Friedman, hearing my case, stated:

“Mr Smith still believes that there are many unanswered questions by the regulatory authorities or by Telstra that he wishes to pursue and he believes these documents will show that his unhappiness with the way he has been treated personally also will flow to other areas such as it will expose the practices by Telstra and regulatory bodies which affects not only him but other people throughout Australia.

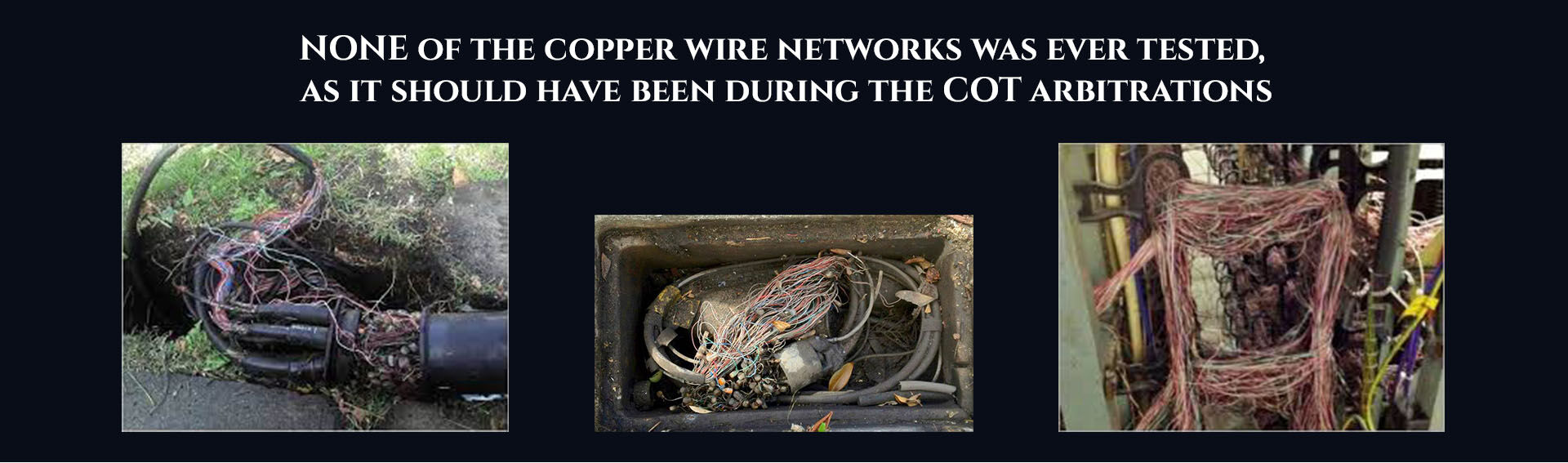

“Mr Smith said today that he had concerns about the equipment used in cabling done at Cape Bridgewater back in the 1990s. He said that it should – the equipment or some of the equipment should have a life of up to 40 years but, in fact, because of the terrain and the wet surfaces and other things down there the wrong equipment was used.”

The telephone issues raised in my arbitration claim from 1994 to 1995 were not resolved during the arbitration. As a result, these problems continued to affect the new owners of my business, who purchased it in December 2001, and persisted until at least November 2006 (See Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story)

During this second AAT hearing in May 2011, I reiterated the telephone problems that had impacted my business since before my arbitration in 1995. I emphasised that the arbitrator failed to investigate or address most of these issues, which allowed them to persist for an additional 11 years after the arbitration concluded. Since that second AAT hearing, and as a result of Australia's National Broadband Network (NBN) rollout, which began in mid-2011 and continues, numerous faults—similar to those I raised during my arbitration and both AAT hearings—have persisted unabated. This is easily verifiable with a simple internet search for “Australia NBN.”

Such as Delimiter’s "Worst of the worst: Photos of Australia’s copper network | Delimiter....

"...23 June 2015: Unions raise doubts over Telstra's copper network; workers using ....

and

"...28 April 2018: NBN boss blames Government's reliance on copper for slow ...

One of the documents I provided to both the arbitrator in 1994 and the AAT in 2008 and again in 2011 is a Telstra FOI (Folio A00253) dated September 16, 1993, titled "Fibre Degradation." It states:

“Problems were experienced in the Mackay to Rockhampton leg of the optical fibre network in December ’93. Similar problems were found in the Katherine to Tenant Creek part of the network in April this year. The probable cause of the problem was only identified in late July, early August. In Telecom’s opinion the problem is due to an aculeate coating (CPC3) used on optical fibre supplied by Corning Inc (US). Optical fibre cable is supposed to have a 40 year workable life. If the MacKay & Katherine experience are repeated elsewhere in the network, in the northern part of Australia, the network is likely to develop attenuation problems within 2 or 3 years of installation. The network will have major QOS problems whilst the CPC3 delaminates from the optical fibre. There are no firm estimates on how long this may take. …