Visitors to this website have drawn parallels between its content and a comprehensive portrayal of criminal activities encompassing fraud.

Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers.

All of the main events highlighted on this website are backed by original documents (confirmation data) linked within the text. By clicking these links, you will open a PDF of the relevant exhibits. This method allows you to follow the various file numbers discussed throughout our pages – see the menu bar above – enabling you to verify our claims. Without these documents, many would struggle to comprehend the extent of suffering endured by Casualty of Telstra (COT) claimants under these unjust circumstances. We’ve added mini-stories to contextualise these exhibits, allowing readers to grasp the true significance of what occurred.

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government owned the country's telecommunications network and the communications carrier, Telecom (now privatised and known as Telstra). This monopoly led to a catastrophic decline in service quality, as the network fell into disrepair. Instead of addressing the unacceptable state of our telephone services as part of the government-endorsed arbitration process—an inherently uneven fight that none of us could win—these issues remained unresolved. It was a battle that cost claimants hundreds of thousands of dollars, yet the crimes committed against us went unacknowledged. Our integrity was viciously attacked, our livelihoods destroyed, and we lost millions, all while our mental health deteriorated. Shockingly, those who orchestrated this corruption continue to wield power today, reinforcing a façade that hides the truth. Our story remains actively suppressed.

PLEASE BE AWARE: That a recent review has uncovered that several of the links referenced in "Absent Justice" have been compromised for reasons that are currently unclear. I met with the website host for "Absent Justice" at 11:15 a.m. on October 7, 2025, Australian time. The cost to re-edit Absent Justice to relocate and attach each of the exhibits to their previous position is beyond my current budget. It previously took me eighteen months to complete Absent Justice, as well as collate each named exhibit to coincide with the damning evidence discussed in this COT story. The Ann Garms COT Case YouTube video was produced shortly before Ann's passing, when she recorded seven chapters of her COT story, which has since been removed online. However, Ann's verbal account of what happened remains intact and can be viewed on Price Waterhouse Coopers Deloitte KPMG. Viewing Ann's side of her COT story, when read in conjunction with my COT story, which is firmly 'so far' etched on absentjustice.com shows there is more truth in what we COT Cases, twenty-one of us, experienced at different levels when dealing with Telstra and their arbitration and mediation lawyers Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now renamed as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne).

Don't forget to hover your mouse or cursor over the following images as you scroll down this home page

The COT cases never had a chance

COT Case Strategy produced by Freehill Hollingdale & Page

Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C

It is imperative to acknowledge the chilling reality that "Absent Justice" stands ominously supported by over 1,300 exhibits—accessible on this site yet shrouded in the depths of a labyrinthine web of evidence files tied to this dark narrative. My initial arbitration claim, submitted back in 1994, mysteriously vanished into thin air, never reaching the arbitrator’s hands. Despite presenting irrefutable proof of this negligence, both the arbitrator and the administrator of the arbitration system brazenly dismissed my submission papers. This deliberate obstruction obliterated my hope of demonstrating that the registered phone complaints were not mere historical grievances, but ongoing crises that continued to jeopardise my telephone-dependent business.

On April 30, 1995, the arbitrator, in a shadowy partnership with DMR & Lane consultants, received a written warning about the unresolved faults plaguing my phone lines. They explicitly stated that they needed more time to investigate the ramifications of these persistent issues. Yet, Dr. Gordon Hughes, now the Principal Partner at: http://Dr Gordon Hughes AM - Lawyer, made the brazen decision to deny DMR & Lane the extra weeks they required to address my claims properly. His justification? An absurd claim that I had not provided a comprehensive list of complaints, even though my two advisors, both former senior police detectives from Queensland, one of whom became a Queensland senator in 2006, had submitted this material at a staggering cost of $56,000 in 1994.

The statement made by DMR & Lane in their Cape Bridgewater Technical Evaluation Report dated 30 April 1995, was provided to the arbitrator as an incomplete report, was not signed off by DMR and Lane when Dr Hughes provided the still incomplete report regardless of my technical consultant George Close & Assocaites writing to Dr Hughes advising it was incomplete. Mr Close received no response. Nor did Derek Ryan, my financial advisor, receive a response from Dr Hughes when he wrote to inform him that the arbitration financial report on my losses was also incomplete → Chapter 2 - Inaccurate and Incomplete

A copy of the statement made in the DMR & Lane Cape Bridgewater Technical Evaluation Report dated 30 April 1995, was provided to the arbitrator as an incomplete report, which was not signed off as a complete record of how DMR & Lane had valued my technical losses, i.e.;

“One issue in the Cape Bridgewater case remains open, and we shall attempt to resolve it in the next few weeks, namely Mr Smith’s complaints about billing problems.

“Otherwise, the Technician Report on Cape Bridgewater is complete.” ( Open Letter File No/47-A to 47-D)

and

“Continued reports of 008 faults up to the present. As the level of disruption to overall CBHC service is not clear, and fault causes have not been diagnosed, a reasonable expectation that these faults would remain ‘open’,” (Exhibit 45-c -File No/45-A)

The corruption runs deeper, as I observed the grim fate of at least two other COT cases during their arbitrations, which mirrored my own betrayal. With "Absent Justice," I compiled a damning exhibit of evidence files to shed light on this sinister pattern of deception and malpractice—an undeniable testament to the moral decay that has plagued this system.

These exhibits contain substantial evidence that upholds the facts and claims made in the story. While about six links have mysteriously encountered issues, this only serves to obscure the true integrity of the material. We urge those who dare to uncover the truth to click on Evidence File-1 and Evidence-File-2. Within lie crucial insights presented in 156 mini-reports that reveal a chilling reality: even amid the deliberate tampering of my exhibits, the remaining evidence in these 151 mini-reports still eerily affirms that my claims are valid. This is a convoluted web of deception that demands to be unravelled.

We sincerely apologise for any inconvenience this situation may have caused and appreciate your understanding as we work to resolve these issues.

You can access my book 'Absent Justice'  here → Order Now—it's Free.

here → Order Now—it's Free.

It presents a compelling narrative that addresses critical societal issues related to justice and equity within Australia's arbitration and mediation processes.

If you see the value in the research and evidence behind this important work, consider supporting Transparency International Australia! Your donation will help raise awareness about the injustices that impact our democracy.

During my phone conversation with Dr. Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator handling my arbitration claim, on May 4, 1995, and in my fax sent on May 5, 1995, I inquired about why DMR & Lane, Dr. Hughes' technical consultants, had not yet addressed my ongoing billing issues in their final report dated April 30, 1995 → Chapter 1 - The Collusion Continues

"A comprehensive log of Mr Smith's complaints does not appear to exist".

However, my Letter of Claim dated 7 June 1994, submitted to arbitration on 15 June 1995 (Refer to Open letter File Nos/46-A to 46-J), shows that a comprehensive log of my complaints did exist.

BCI and SVT Reports - Section One

Who hijacked the BCI and SVT Reports

The following Federal Magistrates Court letter, dated 3 December 2008, from Darren Lewis, was never discussed by the government, the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, or its relevance to several arbitration documents from 1994 to 1995, which were hijacked, i.e., never arrived at the Magistrates Court.

My letter to the Hon. David Hawker MP (see File 274 - AS-CAV Exhibit 282 to 323) indicates that even the Portland Australia Post office staff are aware that the security of specific mail leaving the Portland Post Office cannot be guaranteed. So, what was the use of my mailing my arbitration documents to the arbitrator in 1994 and 1995, and the new owners of my business sending similar Telstra-related documents to the Federal Magistrate Court, when there was a significant chance the mail would not arrive? Darren and Jenny Lewis (the new owners of my business), as stated in their letter of 3 December 2008, is just further alarming information that the government has not transparently investigated (see the following statement by Darren Lewis to the Federal Magistrates Court:

“I was advised by Ms McCormick that the Federal Magistrates Court had only received on 5th December 2008 an affidavit prepared by Alan Smith dated 2 December 2008. PLEASE NOTE: I originally enclosed with Alan Smith’s affidavit in the (envelope) overnight mail the following documents:

- Two 29 page transparent s/comb bound report titled SVT & BCI – Federal Magistrates Court File No (P) MLG1229/2008 prepared by Alan Smith in support of my claims that I had inherited the ongoing telephone problems and faults when I purchased the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp

- Two s/comb transparent bound documents titled Exhibits 1 to 34

- Two s/comb transparent bound documents titled Exhibits 35 to 71 (the attached 71 Exhibits was enclosed in support of Alan Smith’s 29 page report);

- Three CD Disks which incorporated all of the submitted material.

“On learning from Ms McCormick that the information discussed above in points 1 to 4 had not been received by the Federal Magistrates Court I again had a stress attack seizure, a problem I have been suffering with for quite some time due to the predicament I now find myself in and the disbelief that once again my mail has been intercepted. I have attached herewith dated 3rd December 2008, a copy of the Australia Post overnight mail receipt docket numbers SV0750627 and SV0750626 confirming the total cost to send the above aforementioned information was $21.80. I am sure Australia Post would confirm that a large amount of documents would have been enclosed in these two envelopes when they left Portland.” My Story Evidence File 12-A to 12-B

As previously detailed, Australia Post has an unsettling policy: they won't charge postage fees for overnight parcels unless they are stamped and firmly secured within the post office's grasp. It becomes glaringly evident that two crucial parcels failed to reach their intended destination, with all pertinent information initially included, suggesting a deliberate mishandling, or worse, a calculated 'disappearance' between the Portland Post Office and the Magistrates Court.

Throughout this webpage, I’ve outlined a troubling pattern. Many critical Telstra COT-related arbitration documents—such as those that vanished en route to the Federal Magistrates Court in December 2008—were similarly lost back in 1994/95 on their way to the arbitrator’s office. How much incompetence can be chalked up to mere accidents before it begins to smell of something far more sinister?

Darren's letter paints an even darker picture. I assisted him in preparing a bankruptcy appeal against the Australian Taxation Office, which sought to collect back taxes. In doing so, I had to rely on my own evidence, which revealed that the Telstra Corporation, aware of its transgressions, submitted not one but two deceitful and fundamentally flawed Cape Bridgewater reports to the arbitrator. This was no oversight; it was a deliberate effort to mislead the arbitrator into believing that the ongoing phone issues crippling my business had vanished. The deep-rooted corruption and manipulation within this system are alarming, revealing the lengths to which powerful entities will go to protect their interests.

My critical report, which mysteriously vanished during its journey from the Portland Post Office to the Federal Magistrates Court, was meticulously crafted to expose the troubling telephone issues stemming from my arbitration in 1994-95. Despite the arbitration supposedly concluding on May 11, 1995, these persistent faults remained unresolved, wreaking havoc on the phone lines of Darren and Jenny Lewis as they approached their court case in 2008—more than twelve years later → Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story.

This dark situation unfolded because Arbitrator Dr. Gordon Hughes systematically failed to enforce the crucial repairs and installation of new equipment that Telstra had deceitfully promised. They leveraged the funding from COT Cases, like mine, which I provided at an exorbitant cost exceeding $300,000. The government communications authority, AUSTEL (now ACMA), had the audacity to assure us in their publicly released COT Cases Report dated April 21, 1994, that these necessary actions would be taken.

I stress that this promise was never honoured, revealing a web of negligence and betrayal. The Lewis family has endured suffering similar to what my partner, Cathy, and I have faced over the past thirty years, all while corrupt practices and systemic failures remain unaddressed.

The fax imprint across the top of this letter dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the 7 January 1999 Scandrett & Associates fax interception report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations. One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this 7 January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

It is clear from exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

How do you publish a harrowing account of treachery and deceit that has marred various Australian Government-endorsed Arbitrations, all while being denied the exhibits that bear witness to this corruption? How does the author substantiate claims that government public servants shamelessly fed privileged information to the Australian Government-owned telecommunications carrier—an entity that stands as a defendant—yet simultaneously concealed crucial documentation from their own fellow citizens, the claimants?

It’s a tale so entrenched in villainy that even the author finds themselves questioning the very authenticity of their narrative, only to be jolted back to reality by their meticulously kept records. How can one expose the insidious collusion between an arbitrator, appointed government watchdogs, and the defendants? How do you reveal that the defendants—in this case, the Telstra Corporation—engaged in a repugnant scheme where they intercepted and screened confidential communications, storing sensitive material without consent, and then redirected this information to undermine the claimants' position?

The blatant exploitation by Telstra, using this intercepted material to bolster their defence, raises grave concerns about how many other Australian arbitration processes have succumbed to similar heinous acts of electronic eavesdropping. This abhorrent hacking—was it merely a dark chapter of the past, or does it continue to poison legitimate Australian arbitrations today? In January 1999, the arbitration claimants submitted an alarming report to the Australian Government, confirming that confidential documents had been illicitly screened before being delivered to Parliament House in Canberra. Will that damning report ever be laid bare for the Australian public to see?

I've taken the bold step to release the full report on my website, absentjustice.com, and in my new book, ABSENT JUSTICE—a manifesto against this unprincipled conduct.

Fast Track Arbitration Procedure

In August 1993, alarmed by the mounting complaints from citizens—including myself—who had purchased businesses under the premise of reliable telephone services, the Australian Government sanctioned a so-called arbitration and mediation process. Yet, in a shocking turn of events in March 1994, the Government Communications Regulator uncovered that the still-government-owned telecommunications carrier was well aware of the faults plaguing my business but chose to bury that knowledge, a sinister act that tainted the arbitration process overseen by the appointed arbitrator.

It is utterly unfathomable that the Australian Government would endorse a legally binding Arbitration Agreement purportedly drafted by the President of the Australian Institute of Arbitrators, when in fact it was scripted by the very lawyers representing the defendants—the government-owned telecommunications carrier. The corruption deepens with the revelation that this same government refused to investigate the incorporation of a clause crafted by the defendant's lawyers, one that severely restricted the claimants' access to the discovery documents essential for supporting their case!

A Project Manager, commissioned by the Australian Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), was given carte blanche to assist the arbitrator in nine separate arbitrations, mine included. Armed with the defendants' approval, he and his team, without notifying any of the claimants, insidiously sifted through critical documents and decided which would be revealed to the arbitrator and which would be hidden away.

Potential litigants in Australia and Hong Kong should be deeply alarmed: this same Project Manager now operates as a practising arbitrator with offices in both locations. My manuscript, 'Absent Justice', unearths how this resource unit deliberately suppressed four vital documents from the arbitrator during my arbitration, a disgraceful act that saved the defence countless dollars in compensation. Had the arbitrator reviewed those documents, the outcome of my case could have fundamentally changed, saving countless other Australian businesses from suffering the same egregious telephone billing issues.

On November 15, 1995, when the TIO confronted this Project Manager about the alarming absence of key billing claim documents from the arbitrator, he chose the path of deceit, misleading and manipulating the very organisation meant to uphold justice. Over the past thirty years, I have amassed more than 1,230 pages of evidence, a testament to this scandal—one that must be unveiled to ensure such unconscionable conduct does not continue to plague our systems.

In my quest for truth, I have meticulously gathered an impressive collection of 151 mini-reports, each delving into different aspects of this complex ordeal. These reports capture the nuances and intricacies of the situation, providing a comprehensive overview of my findings. Alongside this significant body of work, I have authored a book titled "Abent Justice," which offers a thorough exploration of the themes and challenges I’ve encountered. This book is freely available for download, making it accessible to anyone interested in the subject. Now, at the age of 81, I am excited to embark on creating my second book, "The Brief Case," which promises to reveal even deeper insights and compelling perspectives on the issues at hand.

Don't forget to hover your mouse or cursor over the following images as you scroll down this home page

The type of corroded copper wire problems I was required to register in writing with Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now trading as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne), which I, along with approximately 120,000 other COT-type Australian citizens, experienced, reflects the serious shortcomings in the government's investigation of our claims. My concerns, including those related to the lack of action from the government regulator AUSTEL (now ACMA), were warranted, especially given that the arbitrator and Telstra did not rectify my ongoing billing claims during the arbitration process allowing these ongoing unadresed arbitration problems to ruin the lives of the new owners of my business Jenny and Daren Lewis, who purchased it in December 2001 → Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story and Chapter 5 Immoral - Hypocritical Conduct.

At that time, Telstra was entirely owned by the Australian Government, which meant that the four COT Cases—myself, Ann Garms, Maureen Gilland, and Graham Schorer—were essentially preparing to take on the Government itself, a formidable opponent with a seemingly endless supply of public funds to fight us. The harsh reality was that we signed the Fast Track Settlement Proposal on November 23, 1994, under immense pressure, feeling cornered and outmatched.

What we didn’t know was that a treacherous betrayal was unfolding behind the scenes. Warwick Smith, the administrator of the FTSP and a former government politician now serving as the Australian Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO), was secretly leaking confidential information directly to Telstra’s top brass (see TIO Evidence File No 3-A). This under-the-table deal involved information from government party rooms vital to the COT Cases, ultimately eroding the already fragile integrity of the FTSP. The situation forced us into a labyrinthine and punishing arbitration agreement, meticulously crafted by Telstra’s legal wolves. From the very start, the entire process was a rigged game, a Kangaroo Court.

Adding insult to injury, Dr. Gordon Hughes, the FTSP assessor (who later became the arbitrator), was not merely a passive observer but had a checkered history of manipulating facts. He had previously concealed critical information from Graham Schorer when acting as his lawyer in a Federal Court case against Telstra three years earlier. This dark web of corruption and deceit was meticulously woven around us, revealing the lengths to which those in power would go to protect their interests and silence our fight. The sinister machinations at play would soon become clear in the subsequent revelations, as outlined in the following (Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest) documentation.

Gaslighting

Wayne Goss, the former Premier of Queensland, disclosed that gaslighting tactics were employed against the COT Cases → → (See File Ann Garms 104 Document)

Psychological manipulation

As detailed below and throughout this website, there was a concerted effort to prevent the COT Cases from substantiating their claims at all costs. I faced tremendous pressure to withhold crucial technical documents that I had previously submitted to Freehill Hollingdale & Page, the legal representatives for Telstra. They threatened me with retaliation, insisting that unless I first presented my fault complaints in writing to Freehill, Telstra would categorically refuse to investigate my grievances.

On 1 June 2021, Mathias Cormann officially assumed office as the Secretary-General of the OECD in Paris, France. Similarly to Australia's former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, he possesses comprehensive knowledge about the legitimacy of the COT Cases claims.

Don't forget to hover your mouse/cursor over the kangaroo image to the right of this page → → →

The looming shadows of four letters—dated August 17, 2017, October 6, 2017, October 9, 2017, and October 10, 2017—written by COT Case Ann Garms shortly before her tragic passing, embody a haunting significance (See File Ann Garms 104 Document). Addressed to The Hon. Malcolm Turnbull MP, Australia’s then-Prime Minister, and Senator the Hon. Mathias Cormann, these letters reveal layers of betrayal and unearthly horror. The attachment from Ann's August 6 letter remains a chilling testament to her insight, underscoring secrets that many would wish to keep buried.

On June 1, 2021, Mathias Cormann assumed a pivotal role as Secretary-General of the OECD in Paris. His deep knowledge of the COT Cases claims only amplifies the urgency of what Ann wrote, as whispers of accountability fade like shadows under a flickering streetlight. At the time she penned these courageous letters, I too reached out to Turnbull—a man with a heritage of engaging in matters concerning the public, yet burdened by murky waters of his predecessors. I shared an exhaustive timeline of events with Cormann and a lawyer in Hamilton, Victoria, culminating in a statutory declaration on July 26, 2019, that was meticulously crafted but ultimately drowned in bureaucratic indifference.

But the darkness doesn't merely lie in sealed documents; it extends to chilling allegations of child sexual assault against Senator Bob Collins, whose shadow casts a long pall over Parliament House, Canberra. Such grisly crimes have been documented extensively, a grim reminder of the malevolence that festers in high places—poisoning not just the political landscape, but the very fabric of society.

Ann Garms’ August 17 letter uncovers a grave truth: Wayne Goss, the former Premier of Queensland, disclosed that gaslighting tactics were employed against the COT Cases. This revelation isn't mere gossip; it comes from a credible source within the government, raising the spectre of calculated manipulation.

The suicide of Senator Bob Collins, occurring just before he was set to face serious charges, adds a chilling twist to this narrative. Collins was intertwined in the COT Cases, exacerbating an already convoluted web of deceit. Our desperate pursuit of essential documents, promised to us by Collins' office and vital for our arbitration claims against Telstra, was met with frustrating silence—an eerie echo of promises broken.

Is it too far-fetched to consider that the government was willfully concealing critical evidence? Especially while delving into Collins’ horrific allegations? Compounding these dark suspicions is the unsettling fact that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) were investigating Telstra for allegedly intercepting our arbitration documents and monitoring our communications. A sordid blend of the personal and the political casts a pall over legitimate inquiries, dragging everyone into a vortex of complicity and betrayal.

A closer examination of the COT story unveils a disconcerting reality: despite government assurances, Telstra continued to employ the legal services of Freehill Hollingdale & Page. This hypocrisy screams for scrutiny, as the government had claimed to eliminate Freehill from any COT involvement. Yet, in the shadows of arbitration, Freehill remained engaged—falsifying signatures on critical legal documents, signing off on counter-witness statements as if they were gospel truth, even when such signatures had never been made.

The document from March 1994 (AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings) reveals a troubling reality: government officials tasked with investigating my ongoing telephone issues found my claims against Telstra to be valid. This was not merely an oversight; it indicates a deliberate pattern of misconduct that played out between Points 2 and 212. It is chilling to consider that, had the arbitrator been furnished with this critical evidence, he would likely have awarded me far greater compensation for my substantial business losses.

Three decades have dragged on since these chilling events unfolded. But Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now cloaked as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne, remains disturbingly silent about their actions, which have wreaked unchecked havoc on my life. Their blatant disregard for legality fuels an unconscionable sense of injustice—one that lingers, festering like a wound left untreated. The silence from those who should bear responsibility only amplifies the haunting query: When will the truth, shrouded in darkness, finally emerge?

It was only after this event, and the fact that Telstra was not abiding by all parties in the third week of November 1993 and not arbitration, that I aimed to articulate that 47% of my lost revenues were attributable to a singular club loss. Despite presenting compelling evidence, which included the fact that the AFP had specifically instructed us not to divulge this vital information to Telstra during the AFP's protracted fourteen-month investigation, the arbitrator inexplicably refused to accept it. Initially, he assured me that he would consider my evidence once the AFP allowed me to submit my 'Over Forties Single Club' information to the arbitration process; however, he ultimately failed to honour that commitment. This refusal highlights the deeply flawed nature of the arbitration process, which appeared to prioritise the protection of Telstra's already tarnished reputation over delivering a just and equitable resolution.

I began piecing together the menu bar above in 2007 after receiving a government communications regulatory report that AUSTEL had deliberately concealed, both before and during my government-endorsed arbitration process in 1994. It wasn't until November 2007 that I discovered AUSTEL (now the Australian Communications and Media Authority - ACMA) had compiled an entirely different account of their investigations into my ongoing telephone issues than what was presented to the arbitrator in my case. Had I been privy to those findings, which proved I had a substantially stronger case against Telstra (the new defendants in my arbitration), the arbitrator would have been compelled to award me a significantly greater compensation payout. This damning evidence, supplied to me through the Freedom of Information Act, is attached as AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, further highlighting the depths of this unconscionable betrayal.

In February 1994, I received a troubling communication from the Australian Federal Police (AFP) that would irrevocably alter the course of my business. The AFP explicitly directed me to meticulously sift through the telephone complaints lodged by my single-club patrons since 1990, carefully distinguishing them from a multitude of grievances filed by various educational institutions and organisations throughout the 1990s. This was no regular administrative task; instead, it represented a crucial and urgent measure to confront an imminent crisis of alarming magnitude.

The situation was even more distressing than I could have ever imagined. In a troubling twist of events, the arbitrator, seemingly in collusion with Telstra, which had been under investigation by the Australian Federal Police (AFP), three months before the commencement of my arbitration for having intercepted my phone conversations and hacked into my arbitration faxes and the faxs to and from the Telecommuications Industry was compelled by the AFP to clarify why Telstra employees believed it necessary to intercept my private telephone conversations with various patrons from a singles club. The AFP was also looking into the unsettling possibility that my confidential faxes exchanged with the singles club had been hacked. This breach not only jeopardised the privacy of my Singles Club patrons but also raised serious questions about the disappearance of vital arbitration-related faxes, suggesting a direct connection to the alarming circumstances I now found myself in during this government-endorsed arbitration.

Despite the arbitrator being fully informed of these troubling issues, he shockingly disallowed any evidence related to the singles club from being entered into the arbitration process. To make matters worse, he pointedly stated that my diaries lacked chronological order because I had failed to organise them in a proper folder. This unfortunate misunderstanding stemmed from a recommendation made by the AFP, which had suggested that I include all prior fault statements in my records, along with the emotional expressions documented in my rough complaint notes.

Denise McBurnie, the attorney representing Telstra, emphasised the critical importance of compiling these documents meticulously. She insisted that I required a comprehensive and detailed record of the phone complaints that Telstra had acknowledged, warning that failure to comply would result in Telstra's refusal to investigate my persistent telephone issues. These issues mirrored the very challenges that the AFP had faced during their inquiries. Ultimately, I was instructed to meticulously record these statements in my physical diaries, ensuring that I created a reliable secondary record of the ongoing frustrations and challenges I was facing during this complex and troubling ordeal.

The COT Cases revealed a significant network of corruption and treachery involving Freehill, Hollingdale & Page in their dealings with these matters. Robing Davey, the Chairman of AUSTEL, explicitly stated that Freehill, Hollingdale & Page would have no further involvement in the COT Case issues, as detailed in point 40 of the Prologue Evidence File No/2). Nevertheless, contrary to this official declaration, Freehill proceeded to serve as Telstra's arbitration lawyers in all principal COT arbitrations, marking a notable deviation from established protocol.

Yet, unbeknownst to Mr. Davey, the devious Denise McBurnie had orchestrated a nefarious scheme with her strategic document titled "COT Cases Strategy." This underhanded plan was meticulously crafted to undermine the first four COT Cases and their businesses, locking us out of essential technical information. Instead of transparency, all dialogue was redirected through their legal representatives, masking their duplicitous actions under the guise of Legal Professional Privilege.

In my own experience, when I submitted my flat data to Denise McBurnie in writing, it was under extreme duress. I was kept in the dark about the fact that Telstra’s testing outcomes would be cloaked in Legal Professional Privilege, effectively shrouding me from the truth → (Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C)

The Senate Hansard from 24 and 25 June 1997 revealed a shocking discovery: over two years after my arbitration had concluded, the Senate exposed the unethical manoeuvres of Denise McBurnie and Freehill, Hollingdale & Page, both before the Telecommunications Industry's settlement proposals (TTSP) and during the subsequent Fast Track Arbitration process. With limited financial means to contest the unlawful arbitration, I had no alternative but to document this outrageous betrayal in a book and create this website to unveil the truth.

Tragically, in this battle against profound corruption, Ann Garms and Maureen Gillan are no longer with us, while Graham Schorer now suffers from advanced dementia. This heartbreaking reality leaves me as the solitary voice striving to expose the depraved dishonesty entrenched in the Fast Track Settlement Proposal. What began as a promise for resolution has morphed into a twisted, overly legalistic arbitration farce. Throughout this dark chapter, Dr. Gordon Hughes, the appointed arbitrator, shamefully facilitated changes to the arbitration agreement that shielded his consultants from accountability for negligence. I urge you to examine the twelve mini-reports, which provide detailed information about these occurrences, as outlined in Evidence File-1 and Evidence-File-2.

“COT Case Strategy”

As shown on page 5169 in Australia's Government SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia Telstra's lawyers Freehill Hollingdale & Page devised a legal paper titled “COT Case Strategy” (see Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C) instructing their client Telstra (naming me and three other businesses) on how Telstra could conceal technical information from us under the guise of Legal Professional Privilege even though the information was not privileged.

This COT Case Strategy was to be used against me, my named business, and the three other COT case members, Ann Garms, Maureen Gillan and Graham Schorer, and their three named businesses. Simply put, we and our four businesses were targeted even before our arbitrations commenced. The Kangaroo Court was devised before the four COT Cases were signed, and our arbitration agreements were in place.

It is paramount that the visitor reading absentjustice.com understands the significance of pages 5168 and 5169 at points 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, and 31 SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia, which note:

26. A possible reason for the AFP’s lack of enthusiasm emerged the following year. In 1993 and 1994, the Federal Member for Wannon, Mr David Hawker asked a series of questions about public sector fraud relating to the years 1991-1993. On 28 August 1994, the Sunday Telegraph reported under the headline, "$6.5 million missing in PS fraud," "Workers in sensitive areas including ASIO, the National Crime Authority, Customs, the Family Court, and the Australian Federal Police were convicted of fraud according to information given to Parliament."

27. Apparently the NSW police had a similar problem. According to Mr Saul, he was never interviewed by police, and only token efforts were made to access and seize motel records as evidence. Invariably it was found that moteliers (often former police officers) had been warned to expect a visit. Mr Saul states that a senior police officer within the Professional Responsibility Group of the NSW Police Force (then under the command of former NSW Assistant Commissioner Geoff Schuberg), told him there had been no serious investigation of travel allowance irregularities in NSW—information consistent with a report in the Telegraph Mirror on 19 April 1995, under the headline "Police criminals ‘staying on duty’."

28. In the course of evidence given to the Royal Commission into the NSW Police Force, Assistant Commissioner Schuberg admitted that three detectives from Tamworth who admitted to rorting their travel expenses were dealt with internally and fined rather than charged with fraud. Commissioner Wood asked: "This is a fraud, is it not, of the kind we have seen politicians and others go to jail for? You have people who are proven liars with criminal records who are still carrying out policing and giving evidence?" Assistant Commissioner Schuberg replied: "Yes, I do think it raises a problem." Legal professional privilege.

29. Whether Telstra was active behind-the-scenes in preventing a proper investigation by the police is not known. What is known is that, at the time, Telstra had representatives of two law firms on its Board—Mr Peter Redlich, a Senior Partner in Holding Redlich, who had been appointed for 5 years from 2 December 1991 and Ms Elizabeth Nosworthy, a partner in Freehill Hollingdale & Page who had also been appointed for 5 years from 2 December 1991.

One of the notes to and forming part of Telstra’s financial statements for the 1993- 94 financial year indicates that during the year, the two law firms supplied legal advice to Telstra, totalling $2.7 million, an increase of almost 100 per cent over the previous year. Part of the advice from Freehill Hollingdale & Page was a strategy for "managing" the "Casualties of Telecom" (COT) cases.

30. The Freehill Hollingdale & Page strategy was set out in an issues paper of 11 pages, under cover of a letter dated 10 September 1993 to a Telstra Corporate Solicitor, Mr Ian Row from FH&P lawyer, Ms Denise McBurnie (see Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C). The letter, headed "COT case strategy" and marked "Confidential," stated:

- "As requested I now attach the issues paper which we have prepared in relation to Telecom’s management of ‘COT’ cases and customer complaints of that kind. The paper has been prepared by us together with input from Duesburys, drawing on our experience with a number of ‘COT’ cases. . . ."

31. The lawyer’s strategy was set out under four heads: "Profile of a ‘COT’ case" (based on the particulars of four businesses and their principals, named in the paper); "Problems and difficulties with ‘COT’ cases"; "Recommendations for the management of ‘COT’ cases; and "Referral of ‘COT’ cases to independent advisors and experts". The strategy was in essence that no-one should make any admissions and, lawyers should be involved in any dispute that may arise, from beginning to end. "There are numerous advantages to involving independent legal advisers and other experts at an early stage of a claim," wrote Ms McBride . Eleven purported advantages were listed.

Back then, Mr Redlich was, in most people's eyes, one of the finest lawyers in Australia at that time. He was also a stalwart within the Labor Party, a one-time friend of two Australian Prime Ministers (Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke) and a long-time friend of Mark Dreyfus, Australia's current Attorney General in 2024, so who would be the slightest bit interested in listening to my perspective in comparison to someone so highly qualified and with such vital friends?

And remember, the COT strategy was designed by Freehill Hollingdale & Page when Elizabeth Holsworthy (a partner at Freehill's) was also a member of the Telstra Board, along with Mr Redlich. The whole aim of that ‘COT Case Strategy’ was to stop us, the legitimate claimants against Telstra, from having any chance of winning our claims. Do you think my claim would have even the tiniest possibility of being heard under those circumstances?

While I am not condemning either Mr Redlich or Ms Holsworthy for any personal wrongdoing as Telstra Board members, what I am condemning is their condoning of the COT Cases Strategy designed to destroy any chance of the four COT Cases (which included me and my business), of a proper assessment of the ongoing telephone problems that were destroying our four businesses. I ask how any ordinary person could get past Telstra's powerful Board. After all, in comparison to these so-called highly qualified, revered Aussie citizens, I am just a one-time Ships’ Cook who purchased a holiday camp with a very unreliable phone service.

The fabricated BCI report (see Telstra’s Falsified BCI Report and BCI Telstra’s M.D.C Exhibits 1 to 46 is most relevant because Telstra's arbitration defence lawyers provided it to Ian Joblin, a forensic psychologist who was assigned by Freehill Hollingdale & Page to assess my mental state during my arbitration. It is linked to statements made on page 5169 of the SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia concerning Telstra having adopted the Freehill Hollingdale & Page - COT Case Strategy during the COT arbitrations, which Denise McBurnie of Freehill Hollingdale & Page had spuriously prepared.

What I did not know, when I was first threatened by Telstra in July 1993 and again by Denise McBurnie in September 1993, that if I did not register my telephone problems in writing with Denise McBurnie, then Telstra would NOT investigate my ongoing telephone fault complaints is that this "COT Case Strategy" was a set up by Telstra and their lawyers to hide all proof that I genuinely did have ongoing telephone problems affecting the viability of my business.

The actions of Freehill Hollingdale & Page, currently known as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne, before, during, and in some instances following their representation of Telstra in the government-endorsed arbitrations related to the COT Cases, have resulted in significant discontent and frustration among many participants in the COT Cases. These individuals were compelled to undergo a distressing experience throughout their arbitration and mediation processes, expressing concerns that their cases were severely mishandled and "bastardised." Even after the firm's rebranding, the company has not responded to the following question raised by the administrator of my arbitration, as referenced in the subsequent questions.

On 21 March 1997, twenty-two months after the conclusion of my arbitration, John Pinnock (the second appointed administrator to my arbitration), wrote to Telstra's Ted Benjamin (see File 596 Exhibits AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) asking:

1...any explanation for the apparent discrepancy in the attestation of the witness statement of Ian Joblin .

2...were there any changes made to the Joblin statement originally sent to Dr Hughes compared to the signed statement?"

The fact that Telstra's lawyer, Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehills, signed the witness statement without the psychologist's signature highlights the significant influence Telstra lawyers have over the arbitration legal system in Australia.

The situation involving Telstra's legal representative, Maurice Wayne Condon of Freehills, raises significant ethical and legal concerns. Condon signed a witness statement that falsely claimed it was endorsed by a clinical psychologist, Ian Joblin, despite Joblin's signature not being present at the time it was submitted to the arbitration consultant, rather than the appointed arbitrator, Dr. Gordon Hughes. This oversight—or potential malpractice—raises questions about the integrity of the arbitration process itself.

The TIO and Telstra had jointly appointed Ferrier Hodgson Corporate Advisory to oversee access to all arbitration documents. This firm bore the critical responsibility of determining which documents would be reviewed by the arbitrator and which would be excluded from consideration. This significant role placed immense power in their hands, as their decisions shaped the outcome of numerous claims, including those of individuals like Ann Grams.

On July 11, a letter from Telstra's Steve Black addressed to Warwick was concealed from COT Case Ann Grams during her appeal in the Supreme Court of Victoria. This concealment occurred in the context of Garms’ challenge against Dr. Hughes, who was alleged to have committed gross misconduct in her arbitration. It appears that some of the grievances raised by Grams against Dr. Hughes may have stemmed from negligence by Ferrier Hodgson Corporate Advisory, rather than any malfeasance on the part of Dr. Hughes himself. The ramifications of the failed appeal were staggering, costing Ann Garms over $600,000 and leaving her unaware that she potentially had a valid claim against Ferrier Hodgson Corporate Advisory for their role in this complex case.

Many individuals who have scrutinised various witness statements submitted by Telstra in multiple COT cases—my own included—are alarmed to discover that the Senate was also informed of falsified or altered signatures in my case. Altering a medically diagnosed condition to imply that I was mentally disturbed constitutes serious misconduct that extends beyond simple criminality. Maurice Wayne Condon’s assertion that he had witnessed a signature on the witness statement prepared by Ian Joblin, given the absence of such a signature, further illustrates the urgent need for a comprehensive investigation into the broader implications of the COT cases.

The lack of response from Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne, is troubling. Why have they not issued a formal apology to those affected, including Ann Garms? Their silence raises serious questions about their ethical standards and commitment to their clients' welfare. Particularly concerning is the discrepancy surrounding Ian Joblin’s witness statement; the firm endorsed a document lacking his signature yet attested to its legitimacy. Such a discrepancy not only undermines the integrity of the legal process but also leaves clients grappling with a myriad of unanswered questions, seeking clarity and justice.

Ultimately, Maurice Wayne Condon, as Telstra's legal representative from Freehill Hollingdale & Page, signed a witness statement without securing the psychologist's signature. This raises profound questions about the level of influence and authority that Telstra's legal team wields over the arbitration process in Australia. The integrity of this process is paramount, and it is crucial for all parties involved to confront these issues directly, ensuring accountability and restoring trust among those they represent.

A Secret Deal

Telstra’s Arbitration Liaison Officer wrote to the TIO on 11 July 1994 stating:

“Telecom will also make available to the arbitrator a summarised list of information which is available, some of which may be relevant to the arbitration. This information will be available for the resource unit to peruse. If the resource unit forms the view that this information should be provided to the arbitrator, then Telecom would accede to this request”.

The statement in Telstra’s letter Exhibit 590 in File AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647 “if the resource unit forms the view that this information should be provided to the arbitrator” confirms that both the TIO and Telstra were aware that the TIO-appointed resource unit had been assigned to vet most, if not all, the arbitration procedural documents en route to the arbitrator. If the resource unit decided a particular document was not relevant to the arbitration process, it would not be passed on to the arbitrator or other parties. This particular secret deal has been linked to further clandestine dealings and is discussed in more detail elsewhere on absentjustice.com.

I was unaware I would later need this evidence for an arbitration process. This arbitration process required me to retrieve from Telstra the exact documentation I had previously provided to this legal firm under the Freedom of Information Act. Imagine the frustration of knowing that you had already provided the evidence supporting your case, but Telstra and their lawyers were now withholding it from you.

I have consistently articulated, over an extended period, the necessity and methodology behind transcribing fault complaint records from exercise books into diaries while upholding the accuracy of my chronology of fault events. I must note that I have repeatedly reminded the arbitration project manager of the need to solicit these fault complaint notebooks during my oral arbitration hearing, as evidenced by the meeting transcripts. However, it is noteworthy that Telstra contested the submission of these records, and the arbitrator, without due examination, dismissed their relevance. Notably, Telstra omitted to disclose that Freehill Hollingdale & Page, from June 1993 to January 1994, refrained from documenting my phone complaints as reported by me and refused their release under FOI guidelines based on Legal Professional Privilege.

I posit that the acceptance of these notations from my exercise books as evidence, in conjunction with the retrieval of my fault complaints registered with Freehill Hollingdale & Page in the presence of Telstra's Forensic Documents Examiner, Mr. Holland, would have furnished substantial clarity and dispelled any suspicion of deceit. I acknowledge the potential scepticism concerning the narrative's veracity presented here, attributable to its seemingly incredulous nature.

The arbitrator's written findings in his award did not document the coercion I experienced during arbitration or the threats made and carried out against me by Telstra. He also failed to acknowledge that government solicitors and the Commonwealth Ombudsman had to be involved after Telstra refused to provide the requested documents. These documents were promised to us if the commercial assessment process we had agreed to would be turned into an arbitration process. However, the arbitrator, Dr Gordon Hughes, did mention it in his award.

"… I have considered, and have no grounds to reject the expert evidence provided by Telecom from Neil William Holland, Forensic Document Examiner, who examined the claimant’s diaries and because of numerous instances of non-chronological entries, thereby causing doubt on their veracity and reliability."

Criminal Conduct Example 2

Clicking on the Senate caption below will bring up the YouTube story of Ann Garms (now deceased), who was also named in the Senate as one of the five COT Cases who had to be 'stopped at all costs' from proving her case. The sabotage document Ann Garms discusses in the YouTube video below that was withheld from her by the government-owned Telstra corporation, costing more than a million dollars in arbitration and appeal costs, is now disclosed here as Files 1122 and 1123 - AS-CAV 1103 to 1132. It may be for the best that Ann appears not to have seen this Telstra FOI document before she died.

This strategy was in place before we five signed our arbitration agreements

Stop the COT Cases at all costs

Worse, however, the day before the Senate committee uncovered this COT Case Strategy, they were also told under oath, on 24 June 1997 see:- pages 36 and 38 Senate - Parliament of Australia from an ex-Telstra employee turned -Whistle-blower, Lindsay White, that, while he was assessing the relevance of the technical information which the COT claimants had requested, he advised the Committee that:

Mr White "In the first induction - and I was one of the early ones, and probably the earliest in the Freehill's (Telstra’s Lawyers) area - there were five complaints. They were Garms, Gill and Smith, and Dawson and Schorer. My induction briefing was that we - we being Telecom - had to stop these people to stop the floodgates being opened."

Senator O’Chee then asked Mr White - "What, stop them reasonably or stop them at all costs - or what?"

Mr White responded by saying - "The words used to me in the early days were we had to stop these people at all costs".

Senator Schacht also asked Mr White - "Can you tell me who, at the induction briefing, said 'stopped at all costs" .

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble, Peter Riddle".

Senator Schacht - "Who".

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble and a subordinate of his, Peter Ridlle. That was the induction process-"

From Mr White's statement, it is clear that he identified me as one of the five COT claimants that Telstra had singled out to be ‘stopped at all costs’ from proving their against Telstra’. One of the named Peter's in this Senate Hansard who had advised Mr White we five COT Cases had to stopped at all costs is the same Peter Gamble who swore under oath, in his witness statement to the arbitrator, that the testing at my business premises had met all of AUSTEL’s specifications when it is clear from Telstra's Falsified SVT Report that the arbitration Service Verification Testing (SVT testing) conducted by this Peter did not meet all of the governments mandatory specifications.

Also, in the above Senate Hansard on 24 June 1997 (refer to pages 76 and 77 - Senate - Parliament of Australia Senator Kim Carr states to Telstra’s main arbitration defence Counsel (also a TIO Council Member) Re: Alan Smith:

Senator CARR – “In terms of the cases outstanding, do you still treat people the way that Mr Smith appears to have been treated? Mr Smith claims that, amongst documents returned to him after an FOI request, a discovery was a newspaper clipping reporting upon prosecution in the local magistrate’s court against him for assault. I just wonder what relevance that has. He makes the claim that a newspaper clipping relating to events in the Portland magistrate’s court was part of your files on him”. …

Senator SHACHT – “It does seem odd if someone is collecting files. … It seems that someone thinks that is a useful thing to keep in a file that maybe at some stage can be used against him”.

Senator CARR – “Mr Ward, we have been through this before in regard to the intelligence networks that Telstra has established. Do you use your internal intelligence networks in these CoT cases?”

The most alarming situation regarding the intelligence networks that Telstra has established in Australia is who within the Telstra Corporation has the correct expertise, i.e. government clearance, to filter the raw information collected before that information is impartially catalogued for future use? How much confidential information concerning the telephone conversations I had with the former Prime Minister of Australia in April 1993 and again in April 1994, regarding Telstra officials, holds my Red Communist China episode, which I discussed with Fraser?

More importantly, when Telstra was fully privatised in 2005, which organisation in Australia was given the charter to archive this sensitive material that Telstra had been collecting about their customers for decades?

PLEASE NOTE:

At the time of my altercation referred to in the above 24 June 1997 Senate - Parliament of Australia, my bankers had already lost patience and sent the Sheriff to ensure I stayed on my knees. I threw no punches during this altercation with the Sheriff, who was about to remove catering equipment from my property, which I needed to keep trading. I actually placed a wrestling hold, ‘Full Nelson’, on this man and walked him out of my office. All charges were dropped by the Magistrates Court on appeal when it became obvious that this story had two sides.

In 1997, during the government-endorsed mediation process, Sandra Wolfe, a third COT case, encountered significant injustices and documentation issues. Notably, a warrant was executed against her under the Queensland Mental Health Act (see pages 82 to 88, Introduction File No/9), with the potential consequence of her institutionalisation. It is evident that Telstra and its legal representatives sought to exploit the Queensland Mental Health Act as a recourse against the COT Cases in the event of their inability to prevail through conventional means. Senator Chris Schacht diligently addressed this matter in the Senate, seeking clarification from Telstra by stating:

“No, when the warrant was issued and the names of these employees were on it, you are telling us that it was coincidental that they were Telstra employees.” (page - 87)

Why has this Queensland Mental Health warrant matter never been transparently investigated and a finding made by the government communications regulator?:

Sandra Wolfe, an 84-year-old cancer patient, is enduring severe challenges while striving to seek resolution for her ongoing concerns. Upon reviewing her recent correspondence, it becomes evident that a notable lack of transparency has marked her experience with the Telstra FOI/Mental Health Act issue. The actions of Telstra and its arbitration and mediation legal representatives towards the COT Cases portray a concerning pattern. This is exemplified by the unfortunate outcomes experienced by many COT Cases, including fatalities and ongoing distress. My health struggles, including a second heart attack in 2018, necessitating an extended hospitalisation, underscore the urgency with which these matters must be addressed.

It is my sincere hope that my forthcoming publication will expose the egregious conduct of Telstra, a corporation that warrants closer scrutiny. It is June 2025, and after several emails sent by me to Sandra's email address since the beginning of February 2025, the last email I received told me Sandra's cancer treatment was becoming intolerable. With Sandra living in faraway Queensland, too far for me to travel, I can only assume the worst, or perhaps for the better, with Sandra now at peace.

Criminal Conduct Example 3

TIO Evidence File No 3-A is an internal Telstra email (FOI folio A05993) dated 10 November 1993, from Chris Vonwiller to Telstra’s corporate secretary Jim Holmes, CEO Frank Blount, group general manager of commercial Ian Campbell and other vital members of the then-government-owned corporation. The subject is Warwick Smith – COT cases, and it is marked as CONFIDENTIAL:

“Warwick Smith contacted me in confidence to brief me on discussions he has had in the last two days with a senior member of the parliamentary National Party in relation to Senator Boswell’s call for a Senate Inquiry into COT Cases.

“Advice from Warwick is:

Boswell has not yet taken the trouble to raise the COT Cases issue in the Party Room.

Any proposal to call for a Senate inquiry would require, firstly, endorsement in the Party Room and, secondly, approval by the Shadow Cabinet. …

The intermediary will raise the matter with Boswell, and suggest that Boswell discuss the issue with Warwick. The TIO sees no merit in a Senate Inquiry.“He has undertaken to keep me informed, and confirmed his view that Senator Alston will not be pressing a Senate Inquiry, at least until after the AUSTEL report is tabled.

“Could you please protect this information as confidential.”

Exhibit TIO Evidence File No 3-A confirms that two weeks before the TIO was officially appointed as the administrator of the Fast Track Settlement Proposal FTSP, which became the Fast-Track Arbitration Procedure (FTAP) he was providing the soon-to-be defendants (Telstra) of that process with privileged, government party room information about the COT cases. Not only did the TIO breach his duty of care to the COT claimants, but he also appears to have compromised his own future position as the official independent administrator of the process.

It is highly likely the advice the TIO gave to Telstra’s senior executive, in confidence (that Senator Ron Boswell’s National Party Room was not keen on holding a Senate enquiry), later prompted Telstra to have the FTSP non-legalistic commercial assessment process turned into Telstra’s preferred legalistic arbitration procedure, because they now had inside government privileged information. There was no longer a significant threat of a Senate enquiry.

Was this secret government party-room information passed on to Telstra by the administrator to our arbitrations have anything to do with the Child Sexual Abuse and the cover-up of the paedophile activities by a former Senator who had been dealing with the four COT Cases? The fact that Warwick Smith, the soon-be administrator of the COT settlement/arbitrations, provided confidential government in-house information to the defendants (Telstra) was a very serious matter.

IMPORTANT AUTHOR'S NOTE

When three witnesses and I provided Senator Richard Alston conclusive proof that Warwick Smith had proved privileged COT Case government discussed party room information to Telstra, as the following TIO Evidence File No 3-A confirms, he was shocked. Still, he did say he would follow up this issue with Warwick Smith as a matter of great concern. NONE of the four COT Cases received advice from either Senator Alston or Warwick Smith on why Warwick Smith had been allowed to get away with this matter when it was so important to all four commercial assessment processes.

On 30 November 1993, this Telstra internal memo FOI document folio D01248, from Ted Benjamin, Telstra’s Group Manager – Customer Affairs and TIO Council Member, writes to Ian Campbell, Customer Projects Executive Office. Subject: TIO AND COT. This was written seven days after Alan had signed the TIO-administered Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP). In this memo, Mr Benjamin states:

“At today’s Council Meeting the TIO reported on his involvement with the COT settlement processes. It was agreed that any financial contributions made by Telecom to the Cot arbitration process was not a matter for Council but was a private matter between Telecom, AUSTEL and the TIO.

I hope you agree with this.”

This shows that Telstra was partly or wholly funding the arbitration process.

If the process had been truly transparent, then the claimants would have been provided with information regarding the funds—specifically, the amounts provided to the arbitrator, arbitrator's resource unit, TIO, and TIO special counsel for their individual professional advice throughout four COT arbitrations.

It remains unclear how the arbitrator billed Telstra for his professional fees or how the TIO billed Telstra for his fees, including those of the TIO-appointed resource unit and special counsel. This raises the questions:

Was the arbitrator and resource unit paid every month?

Did the resource unit receive any extra bonus for being secretly appointed as the second arbitrator in determining what arbitration documents the arbitrator was allowed to receive and what was withheld (see letter dated 11th July 1994, from Telstra to Warwick Smith)?

Without knowing how the defendants distributed these payments to the parties involved in the first four arbitrations, it would be impossible for the TIO and AUSTEL (now the ACMA) to continue to state that the COT arbitrations were independently administered.

To summarise the issue: during these four arbitrations, the defence was allowed to pay the arbitrator and those involved in the process. How is this different from the defendant being allowed to pay the judge in a criminal matter? It is a clear and concerning conflict of interest.

Infringe upon the civil liberties.

Most Disturbing And Unacceptable

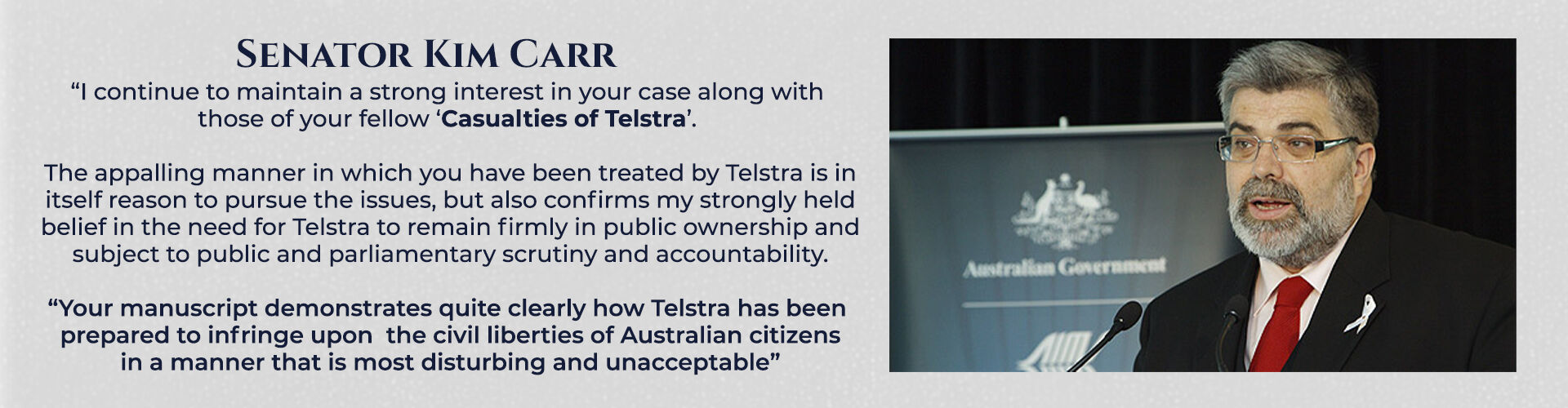

On 27 January 1999, after having also read my first attempt at writing my manuscript, absentjustice.com, the same manuscript I provided to Helen Handbury, Sister to Rupert Murdoch, Rupert Murdoch -Telstra Scandal - Helen Handbury and Senator Kim Carr, who wrote:

“I continue to maintain a strong interest in your case along with those of your fellow ‘Casualties of Telstra’. The appalling manner in which you have been treated by Telstra is in itself reason to pursue the issues, but also confirms my strongly held belief in the need for Telstra to remain firmly in public ownership and subject to public and parliamentary scrutiny and accountability.

“Your manuscript demonstrates quite clearly how Telstra has been prepared to infringe upon the civil liberties of Australian citizens in a manner that is most disturbing and unacceptable.”

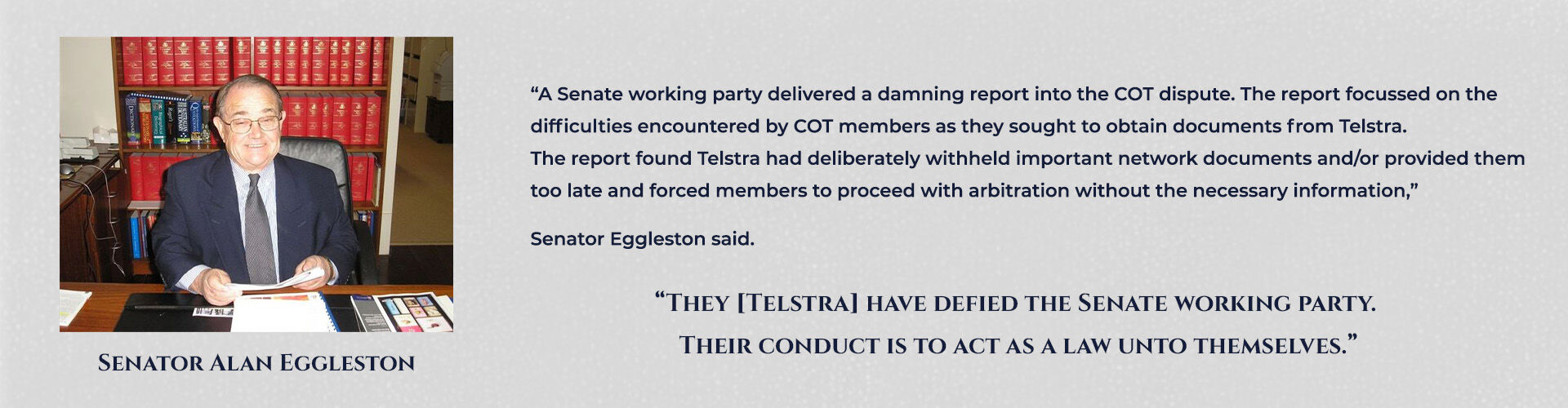

On 23 March 1999, after most of the COT arbitrations had been finalized and business lives ruined due to the hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees to fight Telstra and a very crooked arbitrator, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston and Sen Richard)

These six senators all formally record how those six senators believed that Telstra had ‘acted as a law unto themselves’ throughout all of the COT arbitrations, is incredible. The LNP government knew that not only should the litmus-test cases receive their requested documents but so should the other 16 Australian citizens who had been in the same government-endorsed arbitration process

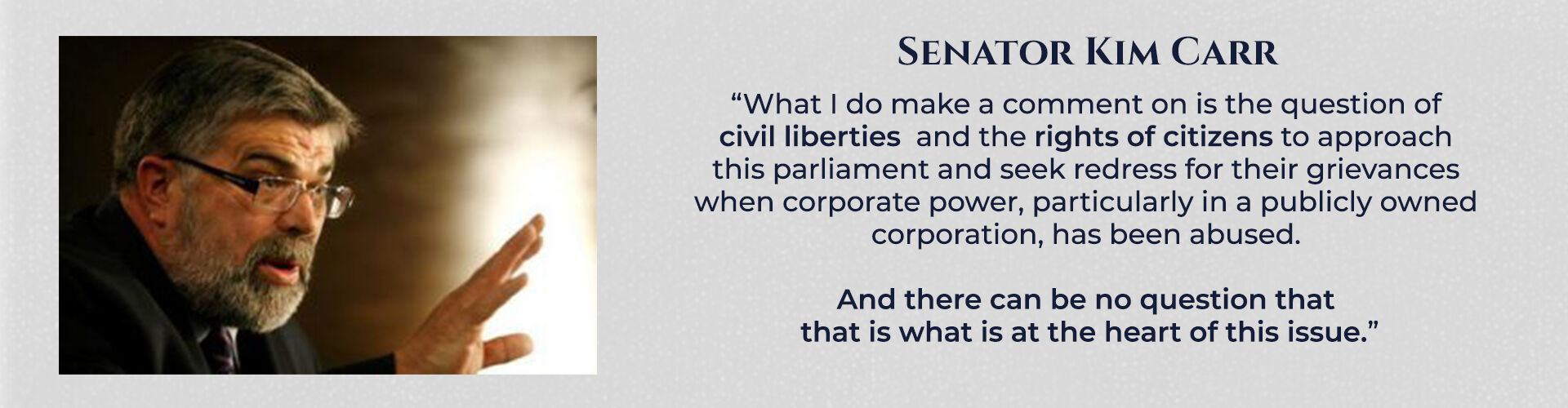

Senator Kim Carr criticised the handling of the COT arbitrations on 11 March 1999, as the following Hansard link shows. Addressing the government’s lack of power, he said:

“What I do make a comment on is the question of civil liberties and the rights of citizens to approach this parliament and seek redress for their grievances when corporate power, particularly in a publicly owned corporation, has been abused. And there can be no question that that is what is at the heart of this issue.”

And when addressing Telstra’s conduct, he stated:

“But we also know, in the way in which telephone lines were tapped, in the way in which there have been various abuses of this parliament by Telstra—and misleading and deceptive conduct to this parliament itself, similar to the way they have treated citizens—that there has of course been quite a deliberate campaign within Telstra management to undermine attempts to resolve this question in a reasonable way. We have now seen $24 million of moneys being used to crush these people. It has gone on long enough, and simply we cannot allow it to continue. The attempt made last year, in terms of the annual report, when Telstra erroneously suggested that these matters—the CoT cases—had been settled demonstrates that this process of deceptive conduct has continued for far too long.” (See parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/displaychamberhansards1999-03-11)

Senator Schacht was even more vocal:

“I rise to speak to this statement tabled today from the working party of the Senate Environment Communications, Information Technology and the Arts Legislation Committee—a committee I served on in the last parliament—that dealt with the bulk of this issue of the CoT cases. In my time in this parliament, I have never seen a more sorry episode involving a public instrumentality and the way it treated citizens in Australia. I agree with all the strong points made by my colleagues on both sides who have spoken before me on this debate. What was interesting about the Senate committee investigating this matter over the last couple of years was that it was absolutely tripartisan—whether you were Labor, Liberal or National Party, we all agreed that something was rotten inside Telstra in the way it handled the so-called CoT cases for so long.

The outcome here today is sad. There is no victory for citizens who have been harshly dealt with by Telstra.”

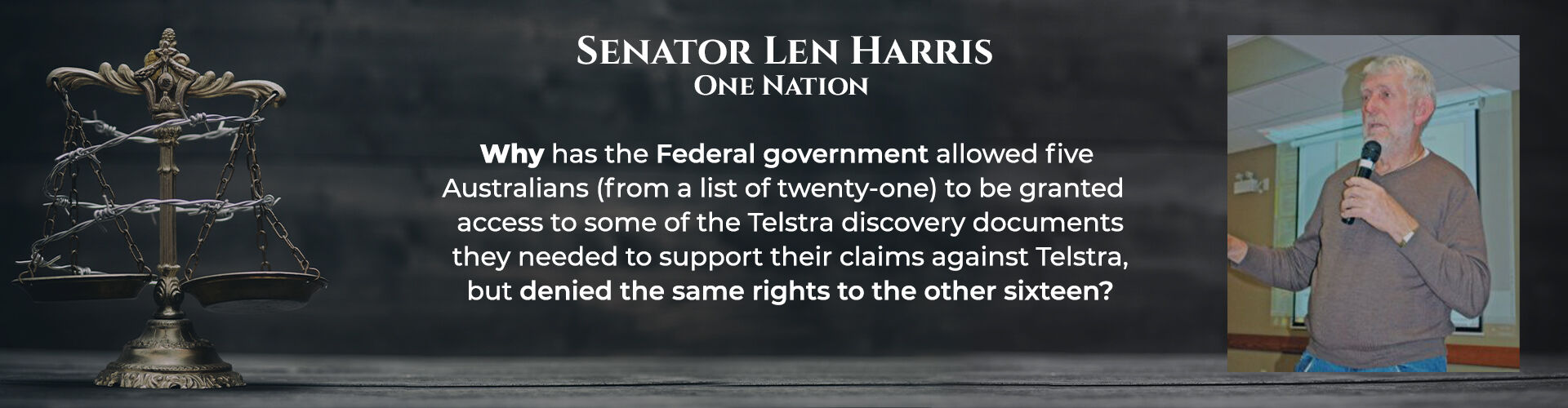

On 25 July 2002, Senator Len Harris travelled from Cairns in Queensland (a trip that took more than seven hours) to meet four other COTs and me in Melbourne to ensure our discrimination claims against the Commonwealth were thoroughly investigated. He was appalled that 16 Australian citizens were so severely discriminated against by the then-coalition government, despite a Senate estimates committee working party being established to investigate all 21 COT-type claims against Telstra.

He was stunned at how I had collated this evidence into a bound submission. Senator Harris read Senator Alan Eggleston’s 9 August 2001 letter warning me that if I disclosed the in-camera Hansard records (supporting my claims that 16 Australian citizens were discriminated against in the most deplorable manner), then I would be held in contempt of the Senate and risk jail. Senator Harris was distraught, to say the least.

At a press conference the next day, Senator Harris aimed questions at the chief of staff to the Hon. Senator Richard Alston, Minister for Communications. He asked:

“Through the following questions, the media event will address serious issues related to Telstra’s unlawful withholding of documents from claimants, during litigation.

Why didn’t the present government correctly address Telstra’s serious and unlawful conduct of withholding discovery and/or Freedom of Information (FOI) documents before the T2 float?

Why has the Federal government allowed five Australians (from a list of twenty-one) to be granted access to some of the Telstra discovery documents they needed to support their claims against Telstra, but denied the same rights to the other sixteen?

Why has the Federal Government ignored clear evidence that Telstra withheld many documents from a claimant during litigation?

Why has the Federal Government ignored evidence that, among those documents Telstra did supply, many were altered or delivered with sections illegally blanked out?” (See Senate Evidence File No 56)

Also, during this same press conference, Senator Len Harris asked many other questions, including why should an owner of a business such as the holiday camp at Cape Bridgewater be forced to sell that business because Telstra had still been unable to fix the ongoing telephone problems that Senator Richard Alston himself had investigated in 1992, ten years previous and concluded were affecting Mr Smith's holiday camp. The telephone problems Mr Smith raised in his 1993/94 arbitration were still being raised with Telstra in 2001, seven years after the arbitration process had failed to rectify those problems.

Are these unaddressed problems more related to my original claims against the government in 1967, after I warned the government about the following issues?

Addendum

British Seaman’s Record R744269 - Open Letter to PM File No 1 Alan Smith's Seaman.

In Chapter 7- Vietnam-Vietcong-2, I delve into the unsettling revelations captured in the Senate Hansard from September 7, 1967. During that session, the Honourable Dr. Rex Patterson, a Labour Party member representing Dawson in Queensland, posed an alarmingly pointed inquiry to the Australian government. He sought assurance that Australian wheat being sent to mainland China was not being funnelled to North Vietnam, an implication that carries dark undertones. This raises a chilling question: was the Liberal-Country Party Coalition government blind in their ambition, utterly indifferent to the fact that Australian wheat could be feeding soldiers fighting against our own troops in the oppressive jungles of North Vietnam?

The government’s cold disregard for the returned Vietnam soldiers—shamed, discarded, and silenced by a toxic blend of ignorance and guilt—casts a long shadow over our nation. Even with the passage of time, the memories remain disturbingly vivid as I embark on writing my autobiography as a Ship's Cook and Steward. My sea voyage aboard the Hopepeak, laden with dark memories and bitter truths, plays a crucial role in this narrative. My journey through various catering establishments, coupled with the lessons learned during my 26 years at sea, has propelled me to act, driven by a haunting desire to support children in need, which is why I acquired my cherished Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp, the very centre of this Telstra government-endorsed arbitration Casulaties of Telstra story.

The government’s cold disregard for the returned Vietnam soldiers—shamed, discarded, and silenced by a toxic blend of ignorance and guilt—casts a long shadow over our nation. Even with the passage of time, the memories remain disturbingly vivid as I embark on writing my autobiography as a Ship's Cook and Steward. My sea voyage aboard the Hopepeak, laden with dark memories and bitter truths, plays a crucial role in this narrative. My journey through various catering establishments, coupled with the lessons learned during my 26 years at sea, has propelled me to act, driven by a haunting desire to support children in need, which is why I acquired my cherished Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp, the very centre of this Telstra government-endorsed arbitration Casulaties of Telstra story.

As I revisit my autobiography, now in the hands of editors and expected to be available online as an ebook by October 2025, I find myself grappling with the convoluted and tragic details that make up this story. Each page stirs a rising tide of anxiety within me. As an octogenarian, I am left to ponder the sinister politics of the Liberal-Country National Government that still leave a sour taste. How could these Australian politicians so callously declare that lives lost in Vietnam were mere collateral damage while prioritising the profits of wheat sales to China? This dispassionate calculation mirrors the actions of the John Howard government, which assisted only five of the litmus test COT Cases while abandoning the remaining sixteen to battle the government-owned Telstra Corporation in court, a betrayal wrapped tightly in a cloak of greed and negligence.

The chilling atrocities committed against their own citizens by the Chinese Red Guards continue to haunt me, lingering in my mind like a dark shadow, even more so than my desperate escape from their gunfire. At the same time, I found myself wrongfully accused of espionage, a label that felt like a noose tightening around my neck. This harrowing chapter in history stands as a haunting stain on humanity, gnawing at my conscience with each passing day. It was not merely the terrifying experience of being forced to march up and down the wharf under the watchful eyes of armed guards, nor the sheer panic of fighting against the guards to avoid a potentially deadly injection with a non-sterile needle that haunted me. Instead, what haunts me is the horrific image of a Chinese nurse, her once beautiful smile marred by blood smeared across her face from a Red Guard baton used to splatter her nose, a mix of fear and defiance in her expression. This chilling vision invaded my dreams for many years after, replaying repeatedly, serving as a stark reminder of the inhumanity I witnessed.

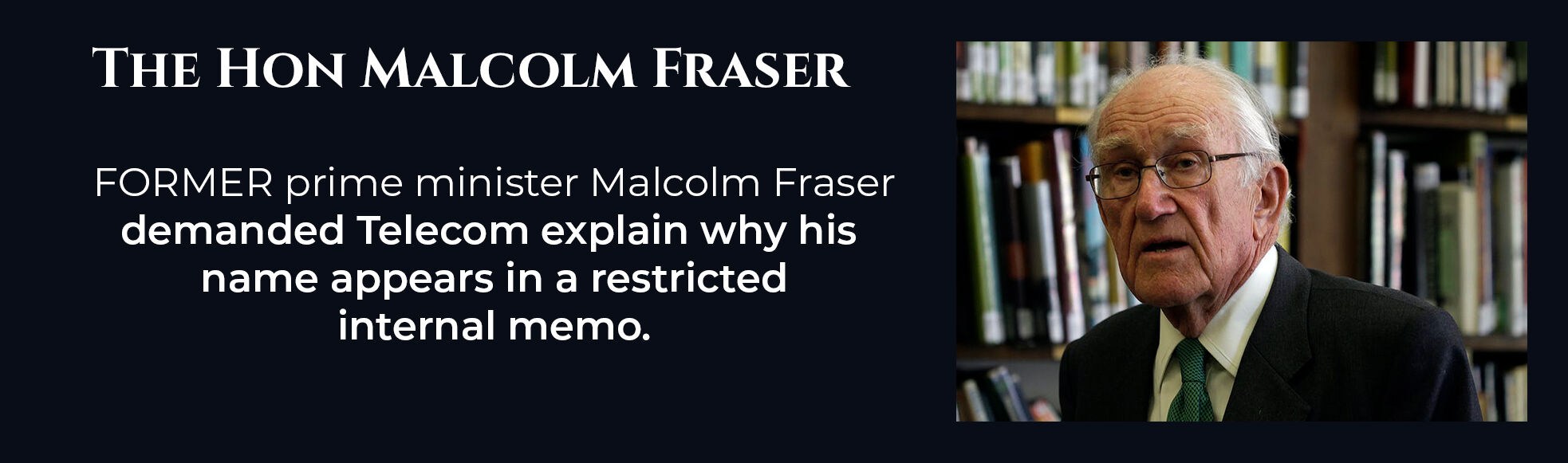

Among the documents I retrieved from Telstra under FOI during my government-endorsed arbitration, I found one particularly alarming file that I later shared with the Australian Federal Police. This document contains a record of my phone conversation with Malcolm Fraser, the former Prime Minister of Australia. To my dismay, this Telstra file had undergone redaction. Despite the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s insistence that I should have received this critical information under the Freedom of Information Act, File 20 → AS-CAV Exhibit 1 to 47, the document and hundreds of other requested FOI documents remain withheld from me as of 2025.

What information was removed from the Malcolm Fraser FOI released document

The AFP believed Telstra was deleting evidence at my expense

During my first meetings with the AFP, I provided Superintendent Detective Sergeant Jeff Penrose with two Australian newspaper articles concerning two separate telephone conversations with The Hon. Malcolm Fraser, a former Prime Minister of Australia. Mr Fraser reported to the media only what he thought was necessary concerning our telephone conversation, as recorded below:

“FORMER prime minister Malcolm Fraser yesterday demanded Telecom explain why his name appears in a restricted internal memo.