Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers.

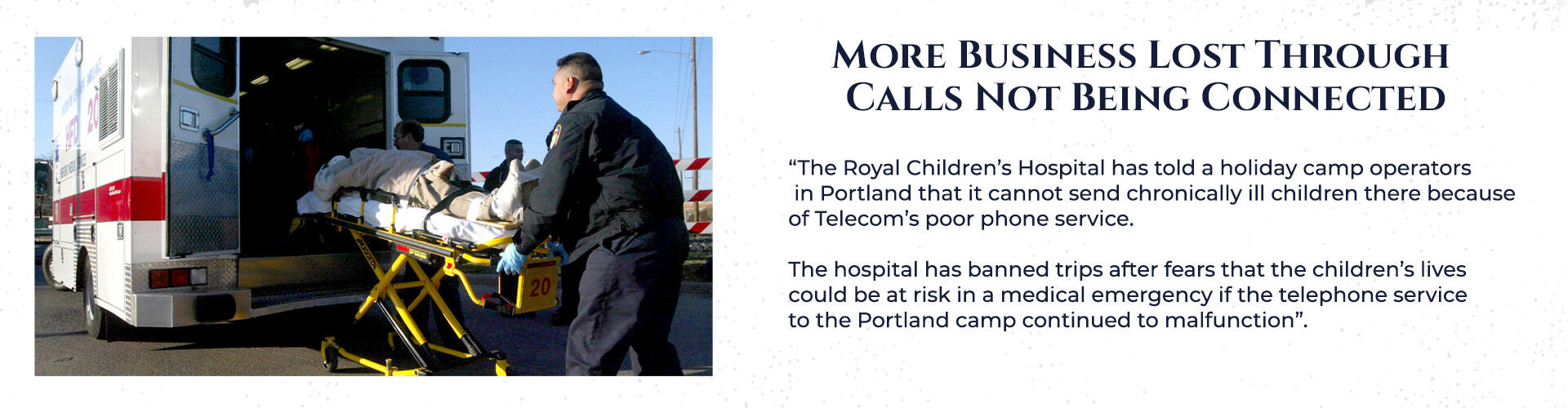

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government owned the country's telecommunications network and the communications carrier, Telecom (now privatised and known as Telstra). This monopoly led to a catastrophic decline in service quality, as the network fell into disrepair. Instead of addressing the unacceptable state of our telephone services as part of the government-endorsed arbitration process—an inherently uneven fight that none of us could win—these issues remained unresolved. It was a battle that cost claimants hundreds of thousands of dollars, yet the crimes committed against us went unacknowledged. Our integrity was viciously attacked, our livelihoods destroyed, and we lost millions, all while our mental health deteriorated. Shockingly, those who orchestrated this corruption continue to wield power today, reinforcing a façade that hides the truth. Our story remains actively suppressed.

What has transpired at the hands of government public servants and their deceptive legal advisors, who have feasted mercilessly on the hard-earned money of taxpayers for decades, is nothing short of a shocking betrayal. Instead of safeguarding the interests of citizens, they allowed Telstra—a colossal government-owned corporation—to control the arbitration process, undermining the very authority of the arbitrator, as the following government records starkly reveal.

Two months into my harrowing arbitration process, which unfolded between June 1994 and April 1995, I found myself ensnared in a twisted web of deceit and treachery. Desperately, I appealed to the arbitrator, urging him to hold Telstra accountable for its despicable and underhanded actions. Instead of reaping the justice I so fervently sought, I was met with an ominous silence and a relentless barrage of obstruction. Fast forward to 2025, and I remain trapped in an agonising limbo, still waiting for crucial discovery documents that Telstra has maliciously and deliberately withheld from me throughout the entire arbitration. My relentless quest for these documents dragged me through two excruciating government Administrative Appeals Tribunals, a nightmare that extended until May 2011—an unconscionable seventeen years after the government duplicitously promised Ann Garms, Maureen Gilland, Graham Schorer, and me that we would receive them if we abandoned our Fast Track Settlement Proposal (FTSP), all under the guise of a non-legal resolution.

The motivations of the government were far darker than mere incompetence; they sought to bury the truth surrounding Senator Bob Collins, the minister overseeing our original claims against Telstra. Collins, a predator cloaked in power, was embroiled in serious allegations of pedophilia, accused of violating at least one child within the so-called safety of his Canberra office. The Australian Federal Police became entangled in this sordid affair, investigating not only Collins but also probing Telstra's dubious involvement in our FTSP issues, creating a perfect storm of corruption and malevolence that loomed ominously over our case.

As members of the COT Cases, we were thrust into this corrupt arbitration process, wholly unaware of the treachery lurking behind the scenes. The arbitrator enforced a treacherous system designed to minimise Telstra's liability, ensuring that the systemic issues still plaguing our businesses were concealed under a cloak of confidentiality. This cruel arrangement shackled us, silencing our voices and preventing us from addressing the ongoing injustices that the government had assured us would be resolved through this new arbitration process.

Throughout my turbulent experiences from 1994 to 1995, Dr. Gordon Hughes, the arbitrator, wrapped himself in layers of secrecy with the duplicitous assistance of the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman. He became a spectre, intentionally unreachable, refusing phone calls—a fact confirmed by his complicit secretary, Caroline Friend, who seemed to take pleasure in reinforcing this veil of evasion. It was only when the Commonwealth Ombudsman intervened—a desperate attempt to wrest control from this deceitful arrangement and compel Telstra to comply with the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act—that a flicker of reluctant cooperation emerged from the shadows. Government solicitors acted as puppeteers, manipulating my arbitration documents, which experienced inexplicable delays, finally arriving on May 23, 1995—two maddening weeks after my arbitration had purportedly concluded.

In a brazen display of contempt for the entire process, the arbitrator audaciously included a dismissive statement in Section 2.23 of his draft award, insisting.

“Although the time taken for completion of the arbitration may have been longer than initially anticipated, I hold neither party nor any other person responsible. Indeed, I consider the matter has proceeded expeditiously in all the circumstances. Both parties have cooperated fully.”

However, this statement was conspicuously omitted from the final award, revealing Dr. Hughes's blatant attempt to mask his actual acknowledgement that he had lost control over the arbitration, which was thrown into chaos by the forces of corruption surrounding him.

For those intrepid enough to delve into the murky depths of Evidence File-1 and Evidence-File-2 or navigate the sinister landscape of absentjustice.com, the true horror of our situation may begin to be unveiled. You may find my stark accusations against deceitful lawyers and conniving government bureaucrats—those I label as "The Brotherhood"—difficult to fathom. Yet by the end of this narrative, the very foundations of Australia’s corrupt legal system will appear as an insidious farce, designed to ensnare the innocent and protect the guilty. Once the claimant and opposing side sign confidentiality clauses in their arbitration agreements, they become ensnared—forgiving the oppressor a shield against justice, stripping us of any real opportunity to contest the unjust awards thrust upon us. The system is a malevolent construct, rigged to protect the powerful, with grotesquely imbalanced odds stacked against anyone audacious enough to confront the dark, treacherous forces lurking in the shadows, ready to pounce on those who dare challenge their sinister status quo.

On 26 September 1997, at the beginning of the Senate Committee hearing that prompted the Senate to start their investigation, the second appointed Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, John Pinnock, who took over from Warwick Smith, formally addressed a Senate estimates committee, refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D). He noted:

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

There is no amendment attached to any agreement, signed by the first four COT members, allowing the arbitrator to conduct those particular arbitrations entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedure, nor was it stated that he would have no control over the process once we had signed those individual agreements. How can the arbitrator and TIO continue to hide under the tainted, altered confidentiality agreement (see below) when that agreement did not mention that the arbitrator would have no control over the arbitration because the process would be conducted 'entirely' outside the agreed procedures

Don't forget to hover your mouse or cursor over the following Confidentiality Agreement. The outcomes of three separate COT arbitrations are evident, raising significant questions about the integrity of the arbitration process. (See Part 2 → Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct).

Altering clause 24 and removing the $250,000 liability caps in clauses 25 and 26 after the first of the four COT Cases, Maureen Gillan disadvantaged the remaining three claimants, Ann Garms, Graham Schorer and me, from using those clauses to appeal the findings made by the arbitrator Dr Gordon Hughes.

The betrayal does not conclude there; the arbitrator’s shocking inaction, coupled with Telstra’s systematic evasion, has systematically eroded the foundation on which the COTs sought solace and justice. Instead of receiving the fairness they deserved, they were met with a betrayal so profound it resonates with echoes of criminality and legal intimidation, leaving their lives—and the lives of their families—in shambles.

The betrayal does not conclude there; the arbitrator’s shocking inaction, coupled with Telstra’s systematic evasion, has systematically eroded the foundation on which the COTs sought solace and justice. Instead of receiving the fairness they deserved, they were met with a betrayal so profound it resonates with echoes of criminality and legal intimidation, leaving their lives—and the lives of their families—in shambles.Delve further into the alarming and often disturbing realms of horrendous crimes, duplicitous criminals, corrupt politicians, and the lawyers who maintain a tight grip on the legal profession in Australia. Descriptors such as shameful, hideous, and treacherous vividly encapsulate the nature of these evil wrongdoers and the impact of their actions.

Unravel the complex web of foreign bribery and insidious corrupt practices, including manipulating arbitration processes through bribed witnesses who shield the truth from the public eye. This narrative encompasses egregious acts of kleptocracy, deceitful foreign corruption programs and the troubling involvement of international consultants whose fraudulent reporting has enabled the unjust privatisation of government assets—assets that were ill-suited for sale in the first place. → Chapter 5 - US Department of Justice vs Ericsson of Sweden.

The link titled Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest unveils perhaps the darkest and most treacherous chapter of this tale, revealing the intricate web of deceit and betrayal lurking behind the scenes of the COT arbitrations. The appointed arbitrator, Dr. Gordon Hughes, and Peter Gamble from Telstra were on opposing sides, yet their shared history was steeped in collusion and manipulation. While Dr. Hughes advocated for Graham Schorer in his Federal Court Action against Telstra between 1990 and 1993, Gamble was secretly working to obstruct justice, actively concealing crucial evidence that could have altered the course of the case.

As destiny would have it, these two figures clashed once more when Graham Schorer, representing a beleaguered group of Telstra complainants—including Ann Garms, Maureen Gillan, and me—embarked on the Telstra Fast Track Settlement Proposals from November 23, 1993, to 1998. This scheme, backed by a government that held a firm grip on Telstra, was nothing more than a facade—twelve other individuals would join us, coining ourselves the Casualties of Telstra.What remains chilling is that I was never informed of the entangled connections between Graham Schorer and Dr. Gordon Hughes, nor was I privy to the fact that Peter Gamble had strategically hidden documents from Graham Schorer throughout the Federal Court proceedings, as explicit in the Senate Hansards of June 24 and 25, 1997, where the principal arbitration engineer was implicated in these deceptions.In my ordeal, Peter Gamble orchestrated a flawed telephone service verification test on my four business lines at my holiday camp on September 29, 1994. He signed a witness statement claiming compliance with government mandates, all while willfully ignoring damning missives from the government communications authority, AUSTEL, on October 11 and November 16, 1994, which denounced those tests as grossly deficient. When I alerted Dr. Hughes to Gamble's treachery, he dismissed my concerns. On April 6, 1995, during a second SVT process at my business, when I dared to question the known faults affecting the Portland Ericsson AXE telephone exchange and the defective Ericsson testing equipment at the Cape Bridgwater switching exchange, both Gamble and Lane Telecommunications Pty Ltd hastily evaded my inquiries, brazenly refusing to test my service lines.The betrayal deepened when Ericsson swept in, acquiring Lane Telecommunications three-quarters of the way through the COT arbitrations, carting off all private and business records related to the COT Cases back to Sweden, thus ensuring that any evidence of wrongdoing vanished into the shadows. (Refer to Chapter 5 - US Department of Justice vs Ericsson of Sweden).Ultimately, I was left with no choice but to sell my business in December 2001, as I found myself ensnared in a web of neglect and malpractice, with no authority willing to investigate my ongoing telephone faults. Dr. Hughes had stated in his final arbitration award that the issues had ceased after July 1994—a blatant lie amidst a convoluted narrative of treachery.Peter Gamble, still lurking in the shadows of Telstra in the 2020s, and Dr. Hughes, now a Principal Partner | Davies Collison Cave Law (AUSTRALIA), symbolise a system corrupted at its core. I am compelled to share this story, hoping that those who read it grasp the gravity of these incredible and sinister events.Anyone linked to Australia’s Establishment, which comprises many powerful figures who profess a commitment to democratic justice, would do well to reevaluate their decisions regarding the awarding of the "Order of Australia" after delving into the unsettling revelations in "Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct and Salvaging What I Could." This chapter uncovers alarming details that expose the dubious integrity of Dr. Gordon Hughes and Warwick Smith during the critical period surrounding the COT arbitrations in my case. Their treacherous act of withholding two crucial letters from me not only compromised my position but also denied my appeal lawyers the essential grounds to challenge the arbitration’s verdict. In light of this, it is nearly unfathomable that these individuals could have been deemed worthy of such a prestigious honor. This concern becomes even more pronounced considering that both Dr. Gordon Hughes and Warwick Smith have previously been awarded this accolade, despite their apparent involvement in deceitful conduct both before and after the contentious COT arbitrations. Their actions raise serious questions about the integrity of the honors they received and suggest a deeply troubling complicity in a system that rewards questionable behavior.

On 24 June 1997, pages 36 to 39, Senate - Parliament of Australia show an ex-Telstra employee turned Whistleblower, Lindsay White, that, while he was assessing the relevance of the technical information which the COT claimants had requested, he advised the Committee that:

Mr White "In the first induction - and I was one of the early ones, and probably the earliest in the Freehill's (Telstra’s Lawyers) area - there were five complaints. They were Garms, Gill and Smith, and Dawson and Schorer. My induction briefing was that we - we being Telecom - had to stop these people to stop the floodgates being opened."

Senator O’Chee then asked Mr White - "What, stop them reasonably or stop them at all costs - or what?"

Mr White responded by saying - "The words used to me in the early days were we had to stop these people at all costs".

Senator Schacht also asked Mr White - "Can you tell me who, at the induction briefing, said 'stopped at all costs" .

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble, Peter Riddle".

Senator Schacht - "Who".

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble and a subordinate of his, Peter Ridlle. That was the induction process-"

From Mr White's statement, it is clear that he identified me as one of the five COT claimants that Telstra had singled out to be ‘stopped at all costs’ from proving my claims against Telstra. One of the named Peter's in this Senate Hansard who had advised Mr White we five COT Cases had to stopped at all costs is the same Peter Gamble who swore under oath, in his 'false sworn witness statement' to the arbitrator, that the testing at my business premises had met all of AUSTEL’s specifications when it is clear from Telstra's Falsified SVT Report that the arbitration Service Verification Testing (SVT testing) conducted by this Peter did not meet all of the governments mandatory specifications.

Corruption within governmental institutions has resulted in the unlawful manipulation of documents faxed from Owen Dixon Chambers, the legal hub of Melbourne, to the Supreme Court of Victoria. This misconduct has enabled criminal activities to persist in at least two cases associated with Telstra's appeal processes.

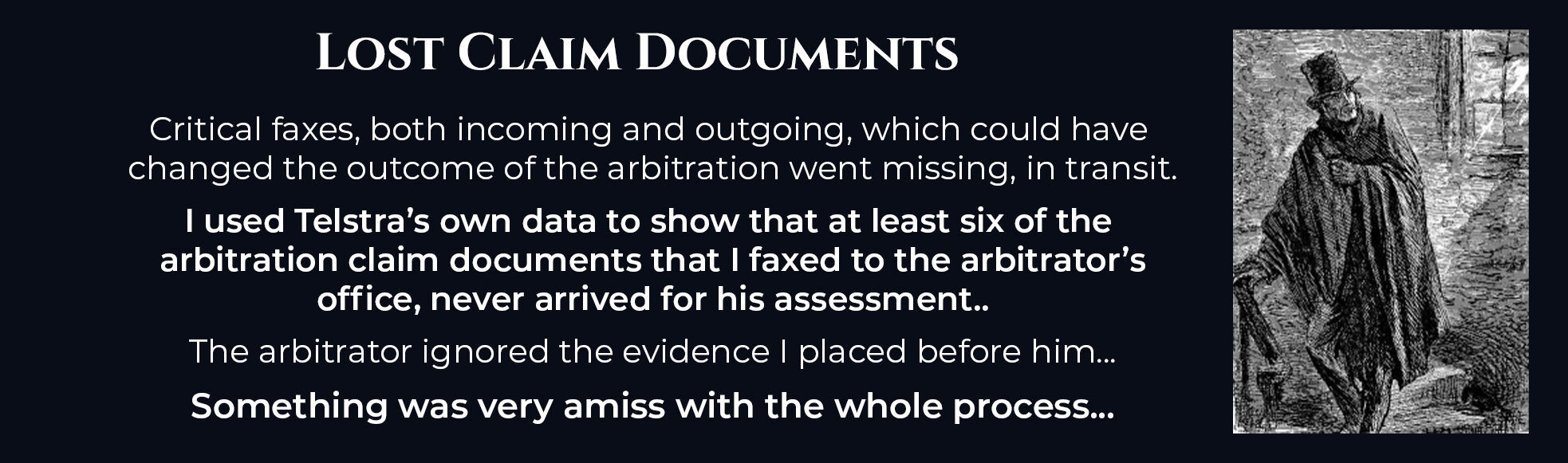

The fax imprint across the top of this letter dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the 7 January 1999 Scandrett & Associates report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations.

One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this 7 January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

I must take the reader forward fourteen years to the following letter dated 30 July 2009. According to this letter dated 30 July 2009, from Graham Schorer (COT spokesperson) and ex-client of the arbitrator Dr Hughes (see Chapter 3 - Conflict of Interest) wrote to Paul Crowley, CEO Institute of Arbitrators Mediators Australia (IAMA), attaching a statutory declaration (see" Burying The Evidence File 13-H and a copy of a previous letter dated 4 August 1998 from Mr Schorer to me, detailing a phone conversation Mr Schorer had with the arbitrator (during the arbitrations in 1994) regarding lost Telstra COT related faxes. During that conversation, the arbitrator explained, in some detail, that:

"Hunt & Hunt (The company's) Australian Head Office was located in Sydney, and (the company) is a member of an international association of law firms. Due to overseas time zone differences, at close of business, Melbourne's incoming facsimiles are night switched to automatically divert to Hunt & Hunt Sydney office where someone is always on duty. There are occasions on the opening of the Melbourne office, the person responsible for cancelling the night switching of incoming faxes from the Melbourne office to the Sydney Office, has failed to cancel the automatic diversion of incoming facsimiles." Burying The Evidence File 13-H.

Dr. Hughes’s failure to disclose the faxing issues to the Australian Federal Police during my arbitration is deeply concerning. The AFP was investigating the interception of my faxes to the arbitrator's office. Yet, this crucial matter was a significant aspect of my claim that Dr. Hughes chose not to address in his award or mention in any of his findings. The loss of essential arbitration documents throughout the COT Cases is a serious indictment of the process.

Even more troubling is that Dr. Hughes was aware of the faxing problems between the Sydney and Melbourne offices prior to his appointment as an arbitrator for seven arbitrations, all of which were coordinated within twelve months. During this time, COT claimants—two in Brisbane and five in Melbourne—frequently voiced their frustrations about the arbitrator's office failing to respond to their faxes. This raises alarming questions regarding potential criminal negligence and the integrity of the arbitration process itself.

It is now 2025, and the Australian Federal Police AFP has still not disclosed to me why Telstra senior management has not been brought to account for authorising this intrusion into my business and private life, regardless of Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stating:

"No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks."

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

The government communications authority, AUSTEL, writes to Telstra's arbitration liaison officer, Steve Black, on 10 February 1994 stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28)

This internal, dated 25 February 1994, is a Government Memo confirming that the then-Minister for Communications and the Arts had written to advise that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone/fax interception. (AFP Evidence File No 4).

During my arbitration, I provided Dr Gordon Hughes with evidence that, between 1992 and 1995, fax interception issues were concerning me and my partner, as we were now travelling to Portland, 18 kilometres away, to talk to our arbitration officials and her daughter, Amanada.

Delve into the intricate and multifaceted issues surrounding corruption in arbitration, a topic that profoundly affects the quest for justice. AbsentJustice.com catalyzes a thorough investigation into the pervasive criminal conduct plaguing government institutions. The website sheds light on disturbing phenomena such as narcissism, where self-interest undermines collective integrity, unconscionable behaviour that disregards ethical standards, and thuggery that employs intimidation to silence dissent. Additionally, it reveals the insidious nature of kleptocracy, where those in power exploit resources for personal gain. This tumultuous landscape is further complicated by the treacherous manipulation of evidence, rendering it nearly indecipherable and obscuring the truth from those seeking accountability.

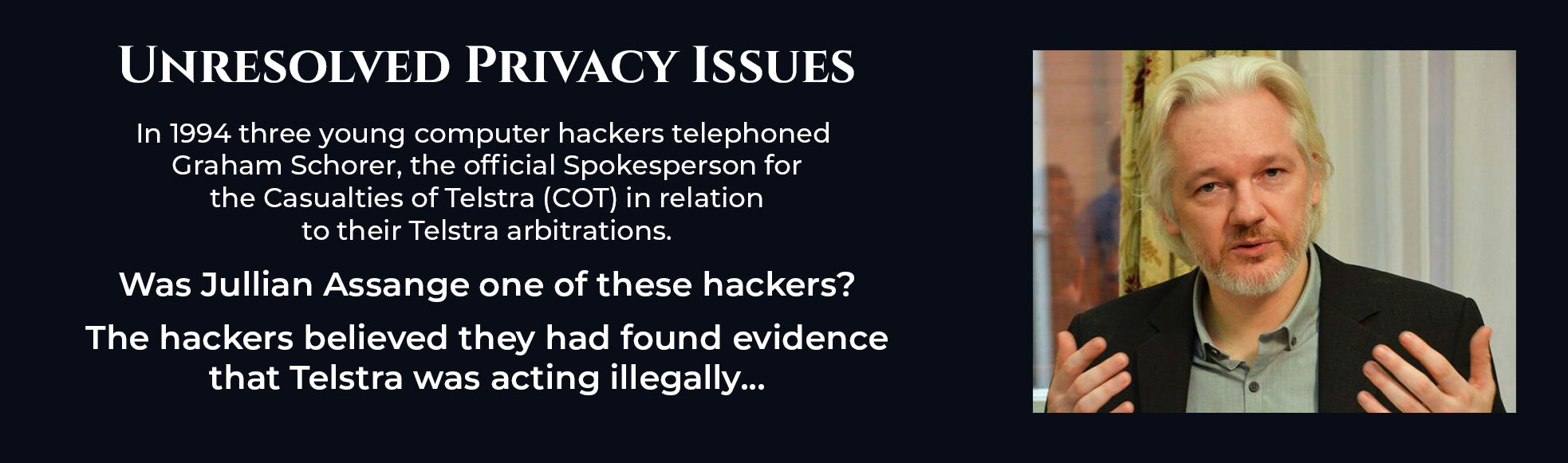

What was the implication of Julian Assange's phone conversations with Graham Schorer, a spokesperson for the Casualties of Telstra (COT), in April 1994? During two separate communications, Assange indicated to Mr. Schorer that the COT cases were subject to electronic surveillance during the arbitration process. (Refer to WikiLeaks exposing the truth).

In April 1994, shortly after my conversation with former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, how did Telstra become aware of my plans to travel to Melbourne weeks before my scheduled trip? This raises several questions, particularly about a person at Telstra called "Micky." Documents on absentjstice.com indicate that at least one local Telstra technician in Portland had been monitoring my phone conversations. Alarmingly, this technician was willing to share sensitive information about my personal and business contacts with this "Micky" individual.

Additionally, it is concerning that the arbitrator did not question this technician regarding the unauthorized disclosure of my private and business information. I had previously informed both the Australian Federal Police (AFP) and the arbitrator about a threat made against me by Telstra's Executive Arbitration liaison officer, Paul Rumble. This threat arose from my cooperation with the AFP. I provided them with evidence that this "Micky" character was acting as an intermediary within Telstra (Refer to pages 12 and 13 → Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1. He had access to the telephone numbers of customers I frequently contacted and those who regularly called me.

Exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) clearly show that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

This individual is the former Telstra Portland technician who supplied an unknown person named 'Micky' with the phone and fax numbers that I used to contact them via my telephone service lines (Refer to Exhibit 518 FOI folio document K03273 - AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541).

The reluctance to investigate these serious violations raises further concerns about privacy and trust within Telstra, the Australian Federal Police and those who administered the COT arbitrations.

The AFP Failed Their Objective

The ongoing issues regarding Rupert Murdoch's phone interceptions in the United Kingdom https://cutt.cx/PCk1 highlight similarities to the phone and fax hacking concerns that impacted the COT case arbitrations from 1994 to 1999. By including thorough and compelling information on my Home page by 28 February, I aim to address significant events that deserve attention. During my arbitration, I contributed valuable assistance to the AFP in their investigations into Telstra's unauthorized interception of my private telephone conversations and arbitration-related faxes tied to my business dealings. I believe that this renewed focus can lead to greater transparency and accountability.

My decision to cooperate with the AFP was motivated by a concerning incident involving Telstra's liaison officers, Paul Rumble and Steve Black. They issued serious threats, indicating that they would cease providing me with Freedom of Information (FOI) documents if Telstra discovered they were being shared with the AFP. Such actions suggested that any subsequent requests for documentation would be systematically denied, potentially obstructing my efforts to challenge Telstra effectively during the arbitration process.

It is essential to underscore that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) made the decision not to support me when I faced a series of alarming threats. This abdication of responsibility allowed Telstra to exert its demands unchecked and without opposition.

Despite investing more than $300,000 in arbitration fees to uncover the unauthorised diversion of my telephone calls and both incoming and outgoing faxes, Dr. Gordon Hughes ultimately failed to arrive at a definitive conclusion. The evidence presented by the Australian Federal Police explicitly confirmed that this diversion was occurring. This information is documented in Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1), yet it did not lead to any findings—neither supporting nor disputing the claims made.

Consider the actions of Telstra during its time as a government-owned enterprise. Like the British Post Office, Telstra engaged in ruthless practices that targeted small business operators, leveraging their position to crush anyone who dared to oppose them. The parallels are chilling. In the UK, the government has resorted to threatening these contractors, employing tactics reminiscent of Telstra’s intimidation in Australia.

After almost two decades, the British public and several British politicians have been saying that this matter is of public interest and should not be concealed (hidden) by the government. It is essential for England's interest that this matter be thoroughly investigated. Click here to watch the Australian television Channel 7 trailer for 'Mr Bates vs the Post Office', which went to air in Australia in February 2024. The British Post Office public servants were aware that the Fujitsu Horizon computer software was responsible for the incorrect billing accounting system, as evidenced in this YouTube link: https://youtu.be/MyhjuR5g1Mc.

Click here to watch Mr Bates vs the Post Office.

If you have been forwarded this newsletter and would like to get it delivered directly to your inbox every time a fresh one is published, please consider making a one-off donation, buying my book The Great Post Office Scandal directly from the publishers or making a donation to the Horizon Scandal Fund.

The "Secret Email" newsletter exposes the dark underbelly of the Post Office Horizon IT scandal in the United Kingdom, a web of deceit that goes far beyond a single incident. This scandal epitomises a pervasive corruption entrenched in Australia’s bureaucratic justice system, revealing a grim reality where those in power operate with impunity.

Don't forget to hover your mouse over the Gaslighting link and/or image, which will help you understand the truth surrounding our story.

Government Corruption - Gaslighting: www.absentjustice.com/tampering-with-evidence/government-corruption--gaslighting. Explore the intricate and troubling intersection of government corruption and the psychological manipulation techniques, commonly known as gaslighting, that are employed against Australian citizens navigating the arduous process of government-endorsed arbitrations.

This narrative reveals a deeply woven tapestry of power dynamics and exploitation that affects not just a few but potentially thousands of individuals desperately seeking redress.

Consider the question: how many citizens in Australia have been subjected to these insidious methods, which aim to derail legitimate investigations into their claims against bureaucrats entrenched in governmental institutions and influential players linked to KPMG?

In my personal experience, I have uncovered compelling and troubling evidence showing that a partner at KPMG deliberately misled the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman on the legitimacy of my arbitration claims. This misinformation was not merely a misstep; it was a calculated move to engineer a false narrative, effectively obstructing any chance of a thorough and unbiased investigation by the Institute of Arbitrators Australia → Price Waterhouse Coopers Deloitte KPMG.

This former KPMG partner now manages two arbitration centres—one situated on the bustling Collins Street in Melbourne, surrounded by the city’s iconic architecture and financial institutions, and the other located in Hong Kong, a global hub of commerce and finance. The existence of these centres raises profound questions about ethical standards and accountability, highlighting the urgent need for systemic reforms. There is a pressing imperative to safeguard citizens from such manipulative practices and to ensure that their legitimate grievances are recognised and addressed in the pursuit of justice.

In the shadowy corridors of power, government corruption festers. Deceptive reporting and a barrage of false information have cloaked the disturbing truths behind the COT cases, allowing them to slip into oblivion. The government-owned Telstra Corporation, a puppet master within this sinister web, has engaged in blatant evidence tampering during arbitration, effectively silencing those who dare to seek justice. Threats hung in the air like a dark cloud, wielded against the vulnerable, as the arbitrator turned a blind eye, complicit in a scheme that denies claimants their rightful day in court. The facade of fairness crumbled, revealing a landscape riddled with betrayal and malice, where truth was sacrificed on the altar of power.

By clicking on the image of the Confidentiality Agreement, you will uncover the hidden truths surrounding my COT story. It is important to note that although the confidentiality clause in this agreement was modified after the COT Cases, both legal advisors and two Senators suggested that it was the definitive arbitration agreement—a claim that is far from true. This flawed agreement continues to be utilised by Wawick Smith, Dr. Gordon Hughes, and other members of the Establishment, who remain committed to protecting an arbitration process that has caused devastating consequences for countless lives.

A deeply sinister pattern unfolds from the outcomes of three distinct COT (Casualties of Telstra) arbitrations, revealing a web of corruption and collusion. Long before these arbitrations even began, Warwick Smith, the first Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman, found himself entrenched in dubious dealings. With his current stature as a prominent banker and recipient of the ‘Order of Australia,’ Smith operates as if he were above the law, his reputation cloaked in shadows. Dr. Goron Hughes, the arbitrator in these troubling cases, was complicit in this scheme, clandestinely aiding Telstra—the defendant—by supplying them with privileged information extracted from covert government discussions about the COT cases.

In a just world, anyone who would betray the trust of twenty-one vulnerable Australian citizens by leaking sensitive party room discussions to a powerful entity like Telstra would face immediate retribution. Yet, in a shocking twist, Warwick Smith managed to dodge accountability, rewardingly ascending to a key front-bench ministerial role in the subsequent John Howard government. Such a trajectory speaks volumes about the murky waters of political alliances and ethical decay.

It becomes chillingly clear that Smith’s insidious advice to Telstra's senior executives regarding discussions within Senator Ron Boswell's National Party Room was a pivot point in this treacherous affair. By informing them that no Senate inquiry would take place until after the release of the AUSTEL (Australian Communications Authority) report on the COT matters—set to go public on April 13, 1994—Smith effectively handed Telstra a shield against scrutiny. This inside knowledge allowed Telstra to transform its initial four COT Case Fast Track Settlement proposals—intended to be a fair, non-legalistic assessment—into a self-serving, legalistic arbitration procedure.

Armed with government secrets and unfettered by the threat of inquiry, Telstra manoeuvred through this labyrinth of deceit with chilling confidence. The walls surrounding their nefarious dealings grew thicker, ensuring that their betrayal of the very citizens they were supposed to serve went unnoticed, buried beneath a veneer of legitimacy crafted by those in power.

TIO Evidence File No 3-A is an internal Telstra email (FOI folio A05993) dated 10 November 1993 from Chris Vonwiller to Telstra’s corporate secretary Jim Holmes, CEO Frank Blount, group general manager of commercial Ian Campbell and other influential members of the then-government-owned corporation. The subject is Warwick Smith – COT cases, and it is marked as CONFIDENTIAL:

“Warwick Smith contacted me in confidence to brief me on discussions he has had in the last two days with a senior member of the parliamentary National Party in relation to Senator Boswell’s call for a Senate Inquiry into COT Cases.

“Advice from Warwick is:

Boswell has not yet taken the trouble to raise the COT Cases issue in the Party Room.

Any proposal to call for a Senate inquiry would require, firstly, endorsement in the Party Room and, secondly, approval by the Shadow Cabinet. …

The intermediary will raise the matter with Boswell, and suggest that Boswell discuss the issue with Warwick. The TIO sees no merit in a Senate Inquiry.“He has undertaken to keep me informed, and confirmed his view that Senator Alston will not be pressing a Senate Inquiry, at least until after the AUSTEL report is tabled.

“Could you please protect this information as confidential.”

Even more troubling, in a stark display of deception and betrayal, the so-called Fast Track Arbitration Procedure (FTAP) was not crafted in good faith by Frank Shelton, the President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia—who would soon be promoted to County Court Judge—but was instead orchestrated by the unscrupulous defendant's lawyers, Freehill Hollingdale and Page. They had the audacity to fax this document to Warwick Smith's office on January 10, 1994. In a brazen act of misrepresentation, Watrwick Smith then informed the government and the lawyers for the COT Cases that Frank Shelton—who was a partner in the very firm that was then exonerated from all liability—for having been party to the drafting the FTAP agreement Chapter 5 Fraudulent Conduct, when he had merely made cosmetic alterations to a document designed to serve the interests of the defendants.

By clicking on the image below, you will see that someone authorized the removal of the $250,000 liability caps outlined in clauses 25 and 26 of my arbitration agreement. Initially, my legal team, along with two Senators, reached a consensus that the arbitration agreement was equitable because the $250,000 liability caps provided me the ability to pursue legal action against the arbitration consultants for negligence. However, the abrupt removal of these critical clauses significantly impacted my situation. As a result, I lost my chance to appeal the arbitration award against the consultants, who acted with gross misconduct, leaving me without the necessary recourse to seek justice.,

What options did we have left? We had lost the arbitration due to our inability to secure the vital documents and faced yet another defeat in our appeal to obtain them. Should we abandon the fight, or is there a path forward that we can still pursue?

As a single operator aged 81, editing these twelve chapters has taken considerably longer than I had hoped; however, browsing these twelve Chapters and some of the 1,600-plus exhibits attached to absentjustice.com, which support the statements made, should convince the devil that the Telstra Corporation has a lot to answer for.

To comprehend the truly sinister nature of the events surrounding Dr. Hughes, we must expose the dark and treacherous details that reveal a web of systemic corruption. Representative Graham Schorer from COT convened with Telstra officials, including the shadowy figure of Dr. Hughes, under the guise of discussing the settlement arbitration process. However, this meeting served as a thin veneer for a betrayal that unfolded in secrecy.

The transcript from this sinister gathering—provided by Telstra themselves—uncovers a chilling truth: the COT claimants made their overwhelming preference for a commercial settlement abundantly clear. Yet, on page three, Dr. Hughes' icy demeanour dismissed their desires without a second thought, insisting that arbitration would somehow be a superior method for resolution. He appointed himself the arbiter of truth, claiming he could provide “appropriate directions for the production of documents,” while darkly asserting that he “would not make a determination on incomplete information.”

Yet, hidden beneath this façade of professionalism lies a treacherous reality. Evidence showcased on absentjustice.com indicates that Dr. Hughes brazenly made a determination, fully cognizant that he was basing his decision on incomplete information. This betrayal became glaringly apparent as I battled overwhelming odds—persistent phone and fax issues wreaked havoc on my business, all while threats loomed large, suffocating my ability to present my case.

This chilling scenario serves as a stark reminder that a system designed to safeguard the vulnerable can easily morph into a weapon wielded by the powerful. In a jaw-dropping display of audacity, Dr. Hughes issued his final findings without mandating Telstra to address the glaring, recurring faults in the services provided. As a result, this segment of my claim should have remained open until Telstra could resolve these ongoing issues, yet it vanished into the shadows.

The arbitrator shamelessly disregarded explicit written advice from the government communication authority, delivered to him and the claimants on April 13, 1994. Such cold treachery cannot go unnoticed; it underscores a corrupt system in which those in power manipulate proceedings for their own gain, leaving the truth buried beneath layers of deception and misconduct —a festering wound at the very heart of justice.

Whistleblowing - Gaslighting

The Narcissus's Chosen Weapon

On the covering page of a joint 10-page letter dated 11 July 2011 to the Hon Robert McClelland, federal attorney-general and the Hon Robert Clark, Victorian attorney-general, I note:

“In 1994 three young computer hackers telephoned Graham Schorer, the official Spokesperson for the Casualties of Telstra (COT) in relation to their Telstra arbitrations.

- Was Jullian Assange one of these hackers?

- The hackers believed they had found evidence that Telstra was acting illegally.

- In other words, we were fools not to have accepted this arbitration file when it was offered to us by the hackers who conveyed to Graham Schorer a sense of the enormity of the deception and misconduct undertaken by Telstra against the COT Cases.” (AS-CAV Exhibit 790 to 818 Exhibit 817)

I also wrote to Hon. Robert Clark on 20 June 2012 to remind him that his office had already received a statutory declaration from Graham Schorer dated 7 July 2011. I also approached other government authorities and provided the Scandrett & Associates report (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), which leaves no doubt that the hackers were right on target regarding Telstra's electronic surveillance of the COT Cases.

If the hackers were Julian Assange, then Julian Assange carried out a duty to expose what he thought was a crime. Significant law enforcement agencies and the media have been asking the Australian public to report incidents that they believe are crimes, as doing so is in the public interest. When I exposed similar crimes to the Australian Federal Police - Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1, I was penalised for it when Telstra carried out their threats.

I have long believed that the hackers who infiltrated Telstra's Lonsdale telephone exchange in Melbourne harboured motives that transcended the mere breach of telecommunications infrastructure. This incident, compellingly documented by journalist Andrew Fowler in his piece "The Most Dangerous Man in the World" for ABC, is part of a larger narrative involving ethical misconduct regarding Telstra's treatment of the COT Cases, a group of individuals who claimed significant injustices in their dealings with the telecommunications giant.

It is essential to review the witness statements from August 8 and 10, 2006.

The Major Fraud Group Barrister, Mr Neil Jepson, asked me to supply all evidence, at the request of the Major Fraud Group Victoria Police, that assisted me in proving that Telstra used three individual reports to support their arbitrations claims against the COT Cases arbitrations, which I did by adding to further re Telstra's Falsified BCI Report to Neil Jepson, the Major Fraud Group asked me to assist them in compiling this evidence for their investigations. I did this over three separate visits to Melbourne, spending two full days at the Major Fraud Group's St. Kilda Road offices on each of those three occasions, assisting the Victoria Police in understanding the relevance of the three fundamentally flawed reports, namely Telstra's Falsified which Telstra used to conceal from the arbitrator and his arbitration advisors how bad the Cape Bridgewater telecommunications network was. AUSTEL (the government communications regulator) had already done their investigations into the grossly deficient Cape Bridgewater and Portland telephone exchange during the early part of my Fast Track Settlement Proposal (which in April 1994 became the arbitration process. It is clear from AUSTEL's investigations leading up to March 1994, as referred to in AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, that at points 2 to 212 in their report, they had uncovered how bad the Cape Bridgewater telecommunications network was and, like Telstra's arbitration defence unit, concealed these findings from the arbitration process.

File 517 AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541 is a Witness Statement dated 10 August 2006 (provided to the Department of Communications, Information, Technology and the Arts (DCITA) sworn out by Des Direen, ex-Telstra Senior Protective Officer, eventually reaching Principal Investigator status. Mr Direen has been brave enough to reveal that, in 1999 / 2000, after he left Telstra, he assisted the Victoria Police Major Fraud Group, particularly Rod Kueris, with their investigations into the COT fraud allegations. I was also seconded by the Major Fraud Group into that investigation as an advisor, showing the Major Fraud Group where, in those arbitrations, Telstra used five known fraudulent, flawed reports provided to the arbitrator and other to convince those parties Telstra had fixed all of their telephone and faxing problems before and/or during the arbitrations when telstra and their lawyers knew duiffenet. (Refer also to the Major Fraud Group Transcript (2)).

Points 12 to 18 in Mr Direen’s statement explained that “From what (he) observed on this day, and applying the knowledge that (he) gained during (his) twelve years at Telstra, (he had) no doubt in (his) mind that the phones at Rod KUERIS’s home address were possibly interfered with".

Within a few weeks of Mr. Direen's involvement in assisting the Major Fraud Group with their ongoing investigations, it became increasingly evident that Detective Sergeant Mr. Rod Kueris was experiencing significant distress regarding the situation. I feel compelled to bring attention to the issue involving Mr. Kueris, mainly because, during that same Major Fraud Group investigation led by Victoria Police, I was in the process of faxing critical documents regarding the falsified Bell Canada International Inc. report, which I had modified for Mr. Neil Jepson's office. It is essential to note that had I not promptly contacted Mr Jepson immediately after sending these faxes, neither of us would have been informed that the documents had been intercepted and had failed to arrive at the Major Fraud Group's fax machine.

I am using the following witness two witness statements File 766 - AS-CAV Exhibit 765-A to 789), because they prove a police officer, when dealing with the Telstra Corporation, was left floundering as were the COT Cases when they were forced into arbitration with the same monster who the arbitrator and administrator of the COT arbitrations were afeared to abandon the COT arbitrations because of the power and influence Telstra has over the legal system in Australia. Please read the following two witness statements.

"I can recall that during the period 2000/2001, I had arranged to meet Detective Sergeant Rod KURIS from the Victoria Police Major Fraud Squad at the foyer of Casselden Place, 2 Lonsdale Street, Melbourne. At the time, I was assisting Rod with the investigation into alleged illegal activities against the COT Cases.

Rod then stated that he wanted me to follow him to the left side of the foyer. When we did this he then directed my attention to a male person seated on a sofa opposite our seat. He then told me that the person had been following him around the city all morning. At this stage Rod was becoming visibly upset and I had to calm him down.Rod kept on saying that he couldn't believe in what was happening to him. I had to again calm him down".

Points 21 and 22 in Mr Direen’s statement also record how, while he was a Telstra employee, he had cause to investigate “… suspected illegal interference to telephone lines at the Portland exchange,” but when he “… made inquiries by telephone back to Melbourne (he) was told not to get involved and that another area of Telstra was handling it” and that “... the Cape Bridgewater complainant was a part of the COT cases” (my Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp) business.

Threats made during my arbitration

On July 4, 1994, amidst the complexities of my arbitration proceedings, I confronted serious threats articulated by Paul Rumble, a Telstra's arbitration defence team representative. Disturbingly, he had been covertly furnished with some of my interim claims documents by the arbitrator—a breach of protocol that occurred an entire month before the arbitrator was legally obligated to share such information. Given the gravity of the situation, my response needed to be exceptionally meticulous. I poured considerable effort into crafting this detailed letter, carefully choosing every word. In this correspondence, I made it unequivocally clear:

“I gave you my word on Friday night that I would not go running off to the Federal Police etc, I shall honour this statement, and wait for your response to the following questions I ask of Telecom below.” (File 85 - AS-CAV Exhibit 48-A to 91)

When drafting this letter, my determination was unwavering; I had no plans to submit any additional Freedom of Information (FOI) documents to the Australian Federal Police (AFP). This decision was significantly influenced by a recent, tense phone call I received from Steve Black, another arbitration liaison officer at Telstra. During this conversation, Black issued a stern warning: should I fail to comply with the directions he and Mr Rumble gave, I would jeopardize my access to crucial documents pertaining to ongoing problems I was experiencing with my telephone service.

Page 12 of the AFP transcript of my second interview (Refer to Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1) shows Questions 54 to 58, the AFP stating:-

“The thing that I’m intrigued by is the statement here that you’ve given Mr Rumble your word that you would not go running off to the Federal Police etcetera.”

Essentially, I understood that there were two potential outcomes: either I would obtain documents that could substantiate my claims, or I would be left without any documentation that could impact the arbitrator's decisions regarding my case.

However, a pivotal development occurred when the AFP returned to Cape Bridgewater on September 26, 1994. During this visit, they began to pose probing questions regarding my correspondence with Paul Rumble, demonstrating a sense of urgency in their inquiries. They indicated that if I chose not to cooperate with their investigation, their focus would shift entirely to the unresolved telephone interception issues central to the COT Cases, which they claimed assisted the AFP in various ways. I was alarmed by these statements and contacted Senator Ron Boswell, National Party 'Whip' in the Senate.

As a result of this situation, I contacted Senator Ron Boswell, who subsequently brought these threats to the Senate. This statement underscored the serious nature of the claims I was dealing with and the potential ramifications of my interactions with Telstra.

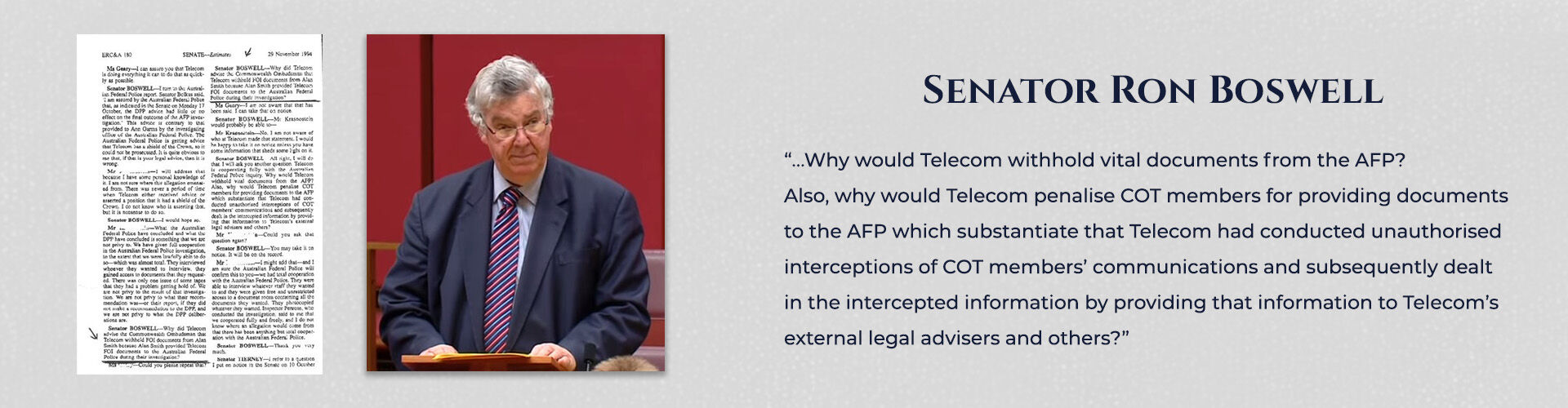

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

Thus, the threats became a reality. What is so appalling about this withholding of relevant documents is this - no one in the TIO office or government has ever investigated the disastrous impact the withholding of documents had had on my overall submission to the arbitrator. The arbitrator and the government (at the time, Telstra was a government-owned entity) should have initiated an investigation into why an Australian citizen, who had assisted the AFP in their investigations into unlawful interception of telephone conversations, was so severely disadvantaged during a civil arbitration.

Pages 12 and 13 of the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 transcripts provide a comprehensive account establishing Paul Rumble as a significant figure linked to the threats I have encountered. This conclusion is based on two critical and interrelated factors that merit further elaboration.

Firstly, Mr. Rumble actively obstructed the provision of essential arbitration discovery documents, which the government was legally obligated to provide under the Freedom of Information Act. This obligation was contingent on my signing an agreement to participate in a government-endorsed arbitration process. By imposing this condition, Mr Rumble undermined a legally established protocol, effectively manipulating the process for his benefit and jeopardizing my legal rights.

Secondly, I uncovered that Mr. Rumble had a substantial influence over the arbitrator, resulting in the unauthorized early release of my arbitration interim claim materials. This premature revelation directly conflicted with the timeline stipulated in the arbitration agreement that Telstra and I had formally signed. Specifically, Telstra gained access to my interim claim document five months earlier than what was permitted under the agreed-upon terms. This breach of protocol violated the integrity of the arbitration process and provided Telstra with an unfair advantage in their response to my claims.

According to the rules governing our arbitration process, Telstra was allocated one month to respond to my claim once it had been submitted in writing as my final claim. Furthermore, the arbitrator was only authorized to release my final claim to Telstra once it was officially confirmed to be complete. The five-month delay in submitting my claim in November 1994 was primarily attributable to Mr. Rumble's deliberate withholding of critical technical information.

In my case, as Telstra's Falsified SVT Report shows, Telstra’s representative, Peter Gamble, attempted to conduct the essential Service Verification Testing (SVT) process. Unfortunately, he had to halt the testing due to unforeseen equipment malfunctions. When AUSTEL questioned how he planned to rectify this inadequate testing at my business, Mr Gamble refused to proceed with any further testing. Instead, he submitted a statutory declaration under oath to the arbitrator, claiming that his SVT process had fully complied with AUSTEL’s requirements. This assertion was far from the truth.

More Threats, this time to the other Alan Smith

Two Alan Smiths (not related) living in Cape Bridgewater.

No one investigated whether another person named Alan Smith, who lived in the Discovery Bay area of Cape Bridgewater, received some of my arbitration mail. Both the arbitrator and the administrator of my arbitration were informed that the road mail sent by Australia Post had not arrived at my premises during my arbitration from 1994 to 1995.

Additionally, the new owners of my business lost legally prepared documents related to Telstra when they attempted to send mail to the Melbourne Magistrates Court. I had prepared these documents in a determined effort to prevent them from being declared bankrupt due to ongoing telephone issues. They were sent from the Portland Post Office but did not arrive (Refer to Chapter 5, Immoral—Hypocritical Conduct).

Stop these people at all costs.

This is the same Peter Gamble who, on 24 June 1997 see:- pages 36 to 38 Senate - Parliament of Australia was named by an ex-Telstra employee turned - Whistle-blower, Lindsay White, that, while he was assessing the relevance of the technical information which the COT claimants had requested under FOI he advised the Committee that:

Mr White - "In the first induction - and I was one of the early ones, and probably the earliest in the Freehill's (Telstra’s Lawyers) area - there were five complaints. They were Garms, Gill and Smith, and Dawson and Schorer. My induction briefing was that we - we being Telecom - had to stop these people to stop the floodgates being opened."

Senator O’Chee then asked Mr White - "What, stop them reasonably or stop them at all costs - or what?"

Mr White responded by saying - "The words used to me in the early days were we had to stop these people at all costs".

Senator Schacht also asked Mr White - "Can you tell me who, at the induction briefing, said 'stopped at all costs" .

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble, Peter Riddle".

Senator Schacht - "Who".

Mr White - "Mr Peter Gamble and a subordinate of his, Peter Ridlle. That was the induction process-"

From Mr White's statement, it is clear that he identified me as one of the five COT claimants that Telstra had singled out to be ‘stopped at all costs’ from proving their against Telstra’.

Peter Gamble's unethical behaviour is significant, but it is also crucial to highlight that David Read from Lane Telecommunications chose not to oversee Gamble’s tests on April 6, 1995. As the technical consultant for the independent arbitrator, Read was responsible for evaluating the COT Cases, which alleged that faulty Ericsson telephone equipment was the source of ongoing complaints from various businesses.

Furthermore, Lane Telecommunications was acquired by Ericsson during the COT arbitration proceedings. This acquisition had profound implications, as it transferred all investigative materials collected by Lane against Ericsson of Sweden—gathered over approximately eight COT arbitrations—into Ericsson's possession. This situation raises significant ethical concerns about the investigation's impartiality, considering that the entity under scrutiny now controls the evidence against it.

Such circumstances challenge Australia’s stated commitment to the rule of law and suggest that it may be one of the few Western nations that allows a principal witness to be financially influenced by those being investigated (Refer to Chapter 5 - US Department of Justice vs Ericsson of Sweden)

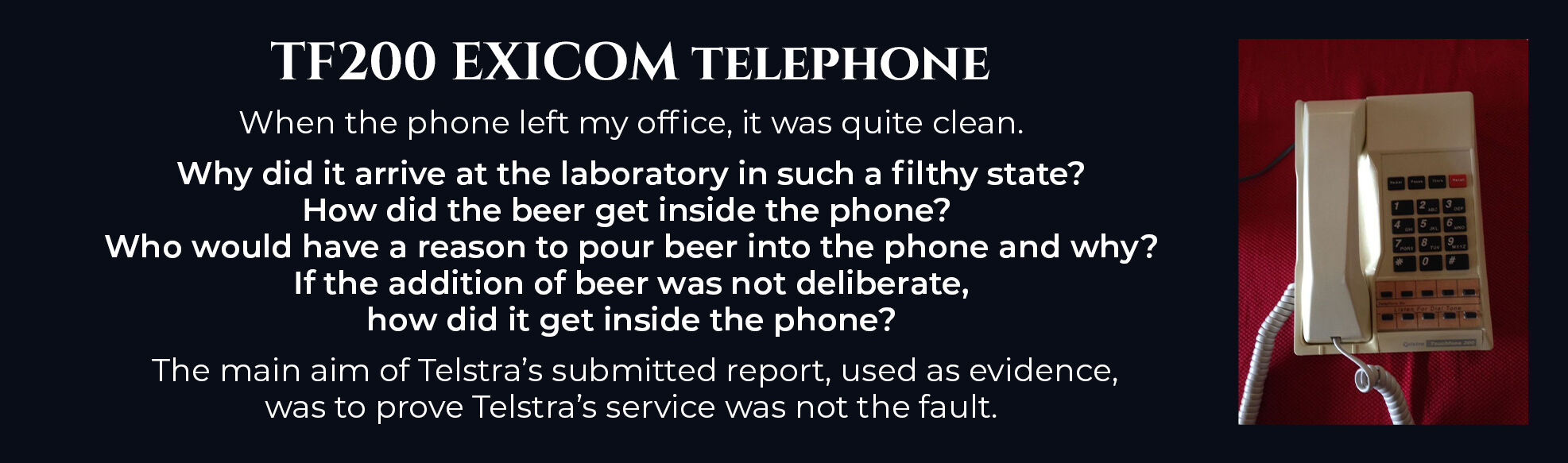

When I phoned AUSTEL’s Cliff Mathieson, a public servant at the government communications regulatory department, to talk about this hang-up fault on 26 April 1994, Mr Mathieson suggested he and I conduct a series of tests on the phone line. He planned for me to hang up and count aloud, from one to 10, while he listened. This first test proved he could hear me count right up to 10. He suggested we try it again and count even further this time. It was still the same situation: he could hear me right through the range as I counted. Then he suggested I switch the phone on that line with a phone connected to another. I did this, and we repeated the counting test with the same results. It was apparent to both that the fault was not in the phone but somewhere in the Telstra network. Mr Mathieson suggested that, as I was in arbitration at the time, I should bring this fault to the attention of Peter Gamble, Telstra’s chief engineer. Lindsay White, a Telstra whistleblower, named Peter Gamble in a Senate estimates committee hearing as the man who said he and Telstra had to stop the first COT five claimants (including me), at all cost, from proving our claims (see Senate Hansard ERC&A 36, Front Page Part One File No/23 dated 24 June 1997).

Unaware of these orders to stop us from five COT cases (at all costs), I switched the phones back to their original lines and phoned Mr Gamble, but did not tell him Mr Mathieson, and I had already tested two phones on the 055 267230 lines. Mr Gamble and I then performed similar tests on the 055 267230 line. Mr Gamble said he would arrange for someone to collect the phone for testing the following day. FOI K00941, dated 26 March 1994, show someone (name redacted) believed this lock-up fault was caused by a problem in the RCM exchange at Cape Bridgewater, see Tampering With Evidence File No 1-A to 1-C. Document K00940, dated the day the tests were performed with Mr Mathieson and Mr Gamble, suggests that Mr Gamble believed the problem was caused by heat in the exchange, see (File No-B), where document folio R37911 states:

“This T200 is an EXICOM and the other T200 is an ALCATEL, we thought that this may be a design ‘fault???’ with the EXICOM so Ross tried a new EXICOM from his car and it worked perfectly, that is, released the line immediately on hanging up. We decided to leave the new EXICOM and the old phone was marked and tagged…” (see File No 1-C).

Another disturbing aspect of this tapering, as evidenced by Telstra's arbitration, is that I volunteered for the Cape Bridgewater Country Fire Authority (CFA) for many years before this tampering occurred. The following chapters show that during my arbitration, Telstra twisted the reason I could not be present for the testing of my TF200 telephone at my premises on a scheduled meeting on the morning of 27 April 1994. Telstra only reported in their file notes (later submitted to the arbitrator) that I refused to allow Telstra to test the phones because I was tired. There was no mention in these file notes that I advised the fault response unit that I had been fighting an out-of-control fire for 14 hours or that my sore eyes made it impossible to observe such testing by Telstra. I fought the fire the previous evening from 6 pm to 9 am the following morning.

It is clear from our Tampering With Evidence page that not only did Telstra set out to discredit me by implying I was just too tired to have my TF200 phone tested, but after Telstra removed the phone, it was tampered with before it arrived at Telstra’s Melbourne laboratories: someone from Telstra poured beer into the phone. In its arbitration defence report, Telstra then alleged that sticky beer was the cause of the phone’s ongoing lock-up problems, not the Cape Bridgewater network. This wicked deed, along with the threats I received from Telstra during my arbitration, is a testament to the fact that my claims should have been investigated years ago. So, even though I carried out my civic duties as an Australian citizen, beyond the call of duty by supplying vital evidence to the AFP and fighting out-of-control fires, I was still penalised on both occasions during my arbitration.

The other twist to this part of my story is how I could have spilt beer into my telephone, as Telstra's arbitration defence documents state, when I had been fighting an out-of-control fire? I certainly would not have been driving the CFA truck or assisting my fire buddies had I been drinking beer. Reading this part of my story will give the reader some idea of the dreadful conduct that we COT Cases had to endure from Telstra as we battled for a reliable phone service.

When I provided the arbitrator and the arbitration Special Counsel with a statutory declaration prepared by Paul Westwood s forensic documents specialist, who advised he would test the collected TF200 and inspect Telstra's laboratory working notes to see how Telstra came up with their findings regarding my drinking habits had caused my phone faults and not the EXICOM TF200 both the arbitrator and arbitration special counsel refused my request to have Telstra's arbitration defence investigated on the grounds fraud had played a significant part in the preparation of the TF200 report.

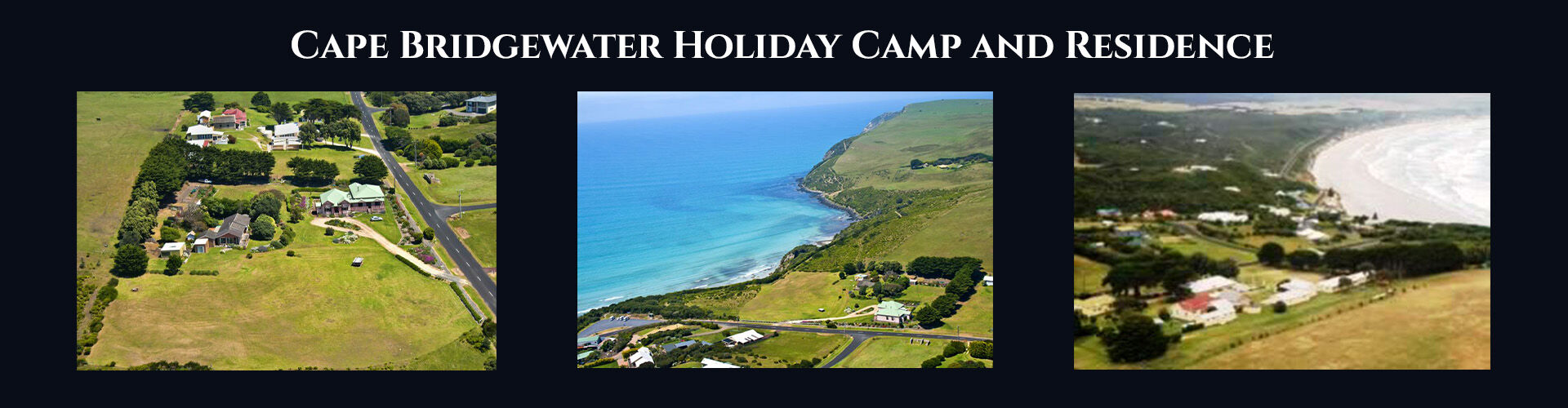

My Holiday Camp was surely situated in a pristine location

If only the telephones had been fit for purpose

On 15 July 1995, two months after the arbitrator's premature announcement of findings regarding my incomplete claim, Amanda Davis, the former General Manager of Consumer Affairs at AUSTEL (now known as ACMA), provided me with an open letter to be shared with individuals of my choosing. This action underscores the confidence she placed in my integrity and professional character:

“I am writing this in support of Mr Alan Smith, who I believe has a meeting with you during the week beginning 17 July. I first met the COT Cases in 1992 in my capacity as General Manager, Consumer Affairs at Austel. The “founding” group were Mr Smith, Mrs Ann Garms of the Tivoli Restaurant, Brisbane, Mrs Shelia Hawkins of the Society Restaurant, Melbourne, Mrs Maureen Gillian of Japanese Spare Parts, Brisbane, and Mr Graham Schorer of Golden Messenger Couriers, Melbourne. Mrs. Hawkins withdrew very early on, and I have had no contact with her since.

The treatment these individuals have received from Telecom and Commonwealth government agencies has been disgraceful, and I have no doubt they have all suffered as much through this treatment as they did through the faults on their telephone services.

One of the striking things about this group is their persistence and enduring belief that eventually there will be a fair and equitable outcome for them, and they are to admired for having kept as focussed as they have throughout their campaign.

Having said that, I am aware all have suffered both physically and their family relationships. In one case, the partner of the claimant has become seriously incapacitated; due, I beleive to the way Telecom has dealt with them. The others have al suffered various stress related conditions (such as a minor stroke.

During my time at Austel I pressed as hard as I could for an investigation into the complaints. The resistance to that course of action came from the then Chairman. He was eventually galvanised into action by ministerial pressure. The Austel report looks good to the casual observer, but it has now become clear that much of the information accepted by Austel was at best inaccurate, and at worst fabricated, and that Austel knew or ought to have known this at the time.”

After leaving Austel I continued to lend support to the COT Cases, and was instrumental in helping them negotiate the inappropriately named "Fast Track" Arbitration Agreement. That was over a year ago, and neither the Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman nor the Arbitrator has been succsessful in extracting information from Telecom which would equip the claimants to press their claims effectively. Telecom has devoted staggering levels of time, money and resources to defeating the claiams, and there is no pretence even that the arbitration process has attemted to produce a contest between equals.

Even it the remaining claimants receive satisfactory settlements (and I have no reason to think that will be the outcome) it is crucial that the process be investigated in the interest of accountabilty of publical companies and the public servants in other government agencies.

Because I am not aware of the exact citrcumstances surronding your meeting with Mr Smith, nor your identity, you can appriate that I am being fairly circimspect in what I am prepared to commit to writing. Suffice it to say, though, I am fast coming to share the view that a public inquiry of some discripion is the only way that the reasons behind the appalling treatent of these people will be brought to the surface.

I would be happy to talk to you in more detail if you think that would be useful, and can be reached at the number shown above at any time.

Thank you for your interest in this matter, and for sparing the time to talk to Alan. (See File 501 - AS-CAV Exhibits 495 to 541 )

Four months after the arbitrator Dr Hughes prematurely brought down his findings on my matters, and fully aware I was denied all necessary documents to mount my case against Telecom/Telstra, an emotional Senator Ron Boswell discussed the injustices we four COT claimants (i.e., Ann Garms, Maureen Gillan, Graham Schorer and me) experienced prior and during our arbitrations (see Senate Evidence File No 1 20-9-95 Senate Hansard A Matter of Public Interest) in which the senator notes:

“Eleven years after their first complaints to Telstra, where are they now? They are acknowledged as the motivators of Telecom’s customer complaint reforms. … But, as individuals, they have been beaten both emotionally and financially through an 11-year battle with Telstra. …

“Then followed the Federal Police investigation into Telecom’s monitoring of COT case services. The Federal Police also found there was a prima facie case to institute proceedings against Telecom but the DPP , in a terse advice, recommended against proceeding. …

“Once again, the only relief COT members received was to become the catalyst for Telecom to introduce a revised privacy and protection policy. Despite the strong evidence against Telecom, they still received no justice at all. …

“These COT members have been forced to go to the Commonwealth Ombudsman to force Telecom to comply with the law. Not only were they being denied all necessary documents to mount their case against Telecom, causing much delay, but they were denied access to documents that could have influenced them when negotiating the arbitration rules, and even in whether to enter arbitration at all. …

“Telecom has treated the Parliament with contempt. No government monopoly should be allowed to trample over the rights of individual Australians, such as has happened here.” (See Senate Hansard Evidence File No-1)

“COT Case Strategy”

As shown on page 5169 in Australia's Government SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia Telstra's lawyers Freehill Hollingdale & Page devised a legal paper titled “COT Case Strategy” (see Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C) instructing their client Telstra (naming me and three other businesses) on how Telstra could conceal technical information from us under the guise of Legal Professional Privilege even though the information was not privileged.

This COT Case Strategy was to be used against me, my named business, and the three other COT case members, Ann Garms, Maureen Gillan and Graham Schorer, and their three named businesses. Simply put, we and our four businesses were targeted even before our arbitrations commenced.

It is paramount that the visitor reading absentjustice.com understands the significance of page 5169 at points 29, 30, and 31 SENATE official Hansard – Parliament of Australia, which note:

29. Whether Telstra was active behind the scenes in preventing a proper investigation by the police is not known. What is known is that, at the time, Telstra had representatives of two law firms on its Board—Mr Peter Redlich, a Senior Partner in Holding Redlich, who had been appointed for 5 years from 2 December 1991 and Ms Elizabeth Nosworthy, a partner in Freehill Hollingdale & Page who had also been appointed for 5 years from 2 December 1991.

One of the notes to and forming part of Telstra’s financial statements for the 1993- 94 financial year indicates that during the year, the two law firms supplied legal advice to Telstra, totalling $2.7 million, an increase of almost 100 per cent over the previous year. Part of the advice from Freehill Hollingdale & Page was a strategy for "managing" the "Casualties of Telecom" (COT) cases.

30. The Freehill Hollingdale & Page strategy was set out in an issues paper of 11 pages, under cover of a letter dated 10 September 1993 to a Telstra Corporate Solicitor, Mr Ian Row from FH&P lawyer, Ms Denise McBurnie (see Prologue Evidence File 1-A to 1-C). The letter, headed "COT case strategy" and marked "Confidential," stated:

- "As requested I now attach the issues paper which we have prepared in relation to Telecom’s management of ‘COT’ cases and customer complaints of that kind. The paper has been prepared by us together with input from Duesburys, drawing on our experience with a number of ‘COT’ cases. . . ."

31. The lawyer’s strategy was set out under four heads: "Profile of a ‘COT’ case" (based on the particulars of four businesses and their principals, named in the paper); "Problems and difficulties with ‘COT’ cases"; "Recommendations for the management of ‘COT’ cases; and "Referral of ‘COT’ cases to independent advisors and experts". The strategy was in essence that no-one should make any admissions and, lawyers should be involved in any dispute that may arise, from beginning to end. "There are numerous advantages to involving independent legal advisers and other experts at an early stage of a claim," wrote Ms McBride . Eleven purported advantages were listed.

Back then, Mr Redlich was, in most people's eyes, one of the finest lawyers in Australia at that time. He was also a stalwart within the Labor Party, a one-time friend of two Australian Prime Ministers (Gough Whitlam and Bob Hawke) and a long-time friend of Mark Dreyfus, Australia's current 2025 Attorney-General in 2024, so who would be the slightest bit interested in listening to my perspective in comparison to someone so highly qualified and with such vital friends?

And remember, the COT strategy was designed by Freehill Hollingdale & Page when Elizabeth Holsworthy (a partner at Freehill's) was also a member of the Telstra Board, along with Mr Redlich. The whole aim of that ‘COT Case Strategy’ was to stop us, the legitimate claimants against Telstra, from having any chance of winning our claims. Do you think my claim would have even the tiniest possibility of being heard under those circumstances?

An investigation conducted by the Senate Committee, which the government appointed to examine five of the twenty-one COT cases as a "litmus test," found significant misconduct by Telstra. This was highlighted by the statements of six senators in the Senate in March 1999:

Eggleston, Sen Alan – Bishop, Sen Mark – Boswell, Sen Ronald – Carr, Sen Kim – Schacht, Sen Chris, Alston Sen Richard.

On 23 March 1999, the Australian Financial. Review reported on the conclusion of the Senate estimates committee hearing into why Telstra withheld so many documents from the COT cases, noting:

“A Senate working party delivered a damning report into the COT dispute. The report focused on the difficulties encountered by COT members as they sought to obtain documents from Telstra. The report found Telstra had deliberately withheld important network documents and/or provided them too late and forced members to proceed with arbitration without the necessary information,” Senator Eggleston said. “They have defied the Senate working party. Their conduct is to act as a law unto themselves.”

Regrettably, because my case had been settled three years earlier, I, along with several other COT Cases, could not take advantage of the valuable insights or recommendations from this investigation. Pursuing an appeal of my arbitration decision would have incurred significant financial costs that I could not afford as shown in an injustice for the remaining 16 Australian citizens.

During the investigation by the Victoria Police Major Fraud Group into the alleged fraudulent conduct by Telstra during and after the COT arbitrations, the Scandrett & Associates report was delivered to Senator Ron Boswell on 7 January 1999. This report confirmed that faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations (refer to Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13). Furthermore, one of the two technical consultants who verified the validity of this fax interception report reached out to me via email on 17 December 2014, emphasising the importance of these findings

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

The evidence within this report Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) also indicated that one of my faxes sent to Federal Treasurer Peter Costello was similarly intercepted, i.e.,

Exhibit 10-C → File No/13 in the Scandrett & Associates report Pty Ltd fax interception report (refer to (Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13) confirms my letter of 2 November 1998 to the Hon Peter Costello Australia's then Federal Treasure was intercepted scanned before being redirected to his office. These intercepted documents to government officials were not isolated events, which, in my case, continued throughout my arbitration, which began on 21 April 1994 and concluded on 11 May 1995. Exhibit 10-C File No/13 shows this fax hacking continued until at least 2 November 1998, more than three years after the conclusion of my arbitration.

The actions taken by Telstra during a government-endorsed arbitration process, as well as during investigations by the Australian Federal Police between 1994 and 1995 and the Victoria Police Major Fraud Group from late 1998 to 2001, are undeniably severe. It is both alarming and unacceptable that Telstra employees have not considered legal repercussions for these actions. This highlights a troubling lack of accountability and transparency, casting doubt on the integrity of the systems meant to protect small businesses and uphold the rule of law.

Exposing the truth meant I faced a possible jail term

It may seem unbelievable, but back in August 2001 and again in December 2004, I received written threats from the Australian Government, warning me that I could be charged with contempt of the Senate if I ever revealed the in-camera Hansard records that were inadvertently shared with me by two high-ranking officers from the Major Fraud Group of Victoria Police. As I celebrate my 81st birthday this May, I keep their names confidential out of respect for these dedicated officers. They could not have possibly been mistaken in their revelations about the systemic corruption the Senate uncovered regarding Telstra during the COT arbitrations.

The Senate Hansards I received at their imposing St Kilda Road complex were supposedly given to me by the police officers I had previously collaborated with during my secondment. They believed these critical documents would support the remaining sixteen COT cases, which were still struggling to resolve their Freedom of Information claims. Sadly, then Prime Minister John Howard’s discriminatory actions placed substantial obstacles in the path of these sixteen cases.