Until the late 1990s, the Australian government fully owned Australia’s telephone network and the communications carrier, Telecom (today privatised and called Telstra). Telecom held the monopoly on communications and let the network deteriorate into disrepair. When four small business owners had severe communication problems (I was the founding member of the four), they were offered a commercial assessment process by the Federal government, which endorsed the process. The arbitrations were a sham: the appointed arbitrator not only allowed Telstra to minimise the claimant's claims and losses, but the arbitrator also bowed down to Telstra and let the carrier run the arbitrations. Telstra committed serious crimes during the arbitrations, yet the Australian government and the Australian Federal Police have not held Telstra, or the other entities involved in these crimes, accountable.

You can access my book 'Absent Justice' here → Order Now—it's Free. It presents a compelling narrative that addresses critical societal issues related to justice and equity within Australia's arbitration and mediation processes. If you see the value in the research and evidence behind this important work, consider supporting Transparency International Australia! Your donation will help raise awareness about the injustices that impact our democracy.

Order Now—it's Free. It presents a compelling narrative that addresses critical societal issues related to justice and equity within Australia's arbitration and mediation processes. If you see the value in the research and evidence behind this important work, consider supporting Transparency International Australia! Your donation will help raise awareness about the injustices that impact our democracy.

How can one present an accurate and compelling narrative about the events that unfolded during various Australian Government-endorsed arbitrations without including supporting exhibits to substantiate those claims? We find ourselves in this predicament due to the pervasive corruption that seems to seep through the very fabric of the government bureaucracy. How can the author convincingly demonstrate—without the looming threat of legal repercussions—that public servants were complicit in providing private and sensitive information to the then-government-owned telecommunications carrier (the defendants), all while deliberately concealing the same crucial documents from the claimants and their fellow Australian citizens?

What strategies can articulate a story so astonishing that even the author questions its credibility, only to feel validated upon reviewing their meticulous records before moving forward? How do you expose the deep-rooted collusion among an arbitrator, various appointed government watchdogs (umpires), and the defendants? How can it be brought to light that the defendants, in this arbitration process—the former government-owned telecommunications carrier—exploited equipment connected to their network to intercept and screen faxed materials sent from our office? They stored these documents without our knowledge or consent and then redirected them to their intended recipients.

The Telstra Corporation, serving as the defendant, likely utilised this intercepted material to fortify their defence in the arbitration, ultimately causing significant harm to the claimants.

How many other arbitration processes across Australia have fallen victim to such invasive hacking tactics? Is electronic eavesdropping—and this violation of confidentiality—still an ongoing reality during legitimate Australian arbitrations today? In January 1999, the claimants alerted the Australian Government to the alarming reality that confidential, arbitration-related documents were being secretly and illegally screened before they reached Parliament House in Canberra. Will that critical report, which has the potential to illuminate these troubling practices, ever see the light of day and be made available to the Australian public?

Documents Telstra released to us years later made it incontrovertibly clear that Telstra knew its systemic problems and how to solve them in rural areas, where many of the COT cases businesses were located.

So, today’s younger generations might find it hard to understand that, only 20 years ago, a corporation like Telstra and its government minders were able to cheat so many Australians into believing it was trying to fix its ailing network. However, in reality, it was band-aiding the many known problems in Australia’s network to defer capital expenditure, as privatisation was on the agenda. Let the shareholders foot the bill was Telstra and its minders' answer to the ongoing problems.

For most rural Australian business operators, running a telephone-dependent business was not like it is today. When our story began, most rural companies were not using the Internet, email, or mobile phones. Checking emails and mobile telephones regularly at the start of each working day was not an option. Mobile phones did not work in most rural locations, and mobile blackspots, even in the city outskirts, were common. It was not until the late 1990s that this new technology became a typical way to run a business.

Before I delve into my "Casualties of Telstra" story, I feel it is essential to provide some context. As a seafarer with 28 years of experience navigating the oceans with diverse nationalities, I have forged strong bonds with many sailors from around the globe. Throughout my journeys, I have been fortunate to work alongside individuals from Asia, Africa, the West Indies, and South America. I can proudly say that they have never engaged in derogatory remarks about other nationalities. This camaraderie extends to seafarers from all the continents I've mentioned, including those from the Americas and Canada.

The Canadians I’ve sailed with stand out for their sense of integrity. While around 99 per cent of my closest friends are Australians, I deeply respect Canadians, who consistently uphold the ideals of fairness and lawfulness. My time aboard Canadian tugs, particularly the Ingram, during significant events like the Bass Strait fires of the mid-1960s highlighted their dedication and professionalism.

Now, turning to a troubling situation involving Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI), which the Australian government commissioned to investigate widespread telephone issues across the country. BCI set out to conduct tests based on information about various telephone exchanges, believing they were testing the correct infrastructures. Unfortunately, it was later revealed that the exchanges they were led to believe they were testing were not the actual locations where the tests took place.

I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action

The Canadian government ministers’ office wrote back on 7 July 1995, noting:

"In view of the facts of this situation, as I understand them, I believe you are taking the most appropriate course of action in contacting BCI directly with respect to the alleged errors in their test report, should you feel that they could assist you in your case."

On June 29, 1995, the Canadian government raised serious concerns regarding the accuracy of test results provided by Telstra's legal representatives, Freehill Hollingdale & Page (now operating as Herbert Smith Freehills in Melbourne). These contentious test results from Bell Canada International Inc. were submitted for review to Mr. Ian Joblin, a clinical psychologist, who was set to travel to Portland for an assessment of my mental health amid ongoing arbitration proceedings.

DMR Group Inc. Canada was brought into the arbitration process in March 1995 by the arbitration administrators, ten months after it was learned the original arbitration consultants had admitted they had a gigantic conflict of interest, regardless of their having signed the arbitration confidentiality papers in April 1994. At the time, Telstra had 47 of the most prestigious legal firms in Australia and just about all of the recognised telecommunications in Victoria on retainer. I had to source a technical consultant, George Close & Associates, who lived in Buderim in Queensland, 1000 kilometres away.

In the 1980s and 1990s, taking a stand against Telstra was an unthinkable move for any reputable professional. The sheer power that Telstra wielded in the telecommunications sector meant that defying them could lead to immediate and devastating consequences, such as the abrupt termination of contracts that businesses had relied on for years. As you immerse yourself in the following story, you will discover that Telstra's approach was not just about issuing threats; they were unflinching in their resolve and acted on those threats with alarming certainty.

After conducting an exhaustive review of the compelling evidence surrounding DMR Group Inc. (Canada), I have arrived at a deeply troubling realisation. Paul Howell, a highly regarded Principal Technical Arbitration Consultant, was dispatched from Canada with a specific mandate: to investigate the serious technical grievances I raised against Telstra between 1994 and 1995. My complaints stemmed from alarming and deceptive practices that Telstra engaged in, particularly their troubling reliance on falsified testing results provided by Bell Canada International Inc. (BCI) at the Cape Bridgewater Telstra facility. These misleading results led the arbitrator down a misguided path, resulting in a conclusion contradicting my lived experiences, leading him to dismiss my claims of ongoing telephone faults.

What amplifies the distressing nature of this situation is the unsettling realisation that the government communications authority was aware of Telstra's flawed testing methodologies. These methods were manifestly inadequate for identifying the recurring systemic issues I had consistently reported. This troubling information is painstakingly documented in their report dated March 1994, where specific points—particularly AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings at 210, 211, and 212—stand out for their glaring exposure of a profound disregard for the validity of the tests.

Deepening this narrative of frustration is the painful understanding that neither DMR Group Inc. Canada nor Lane Telecommunications possesses any obligation to take action in investigating or resolving the persistent telephone faults that have plagued my service for years. Point 2.23 of their report starkly highlights the unsettling reality that the failure to investigate these ongoing issues has left them unresolved and exposed. The arbitration report, dated April 30, paints a grim and unflattering portrait of the process, suggesting that Howell's journey from Canada was merely a procedural formality that endorsed a deeply flawed report. This report not only contributed to the downfall of my business but also wreaked havoc on my personal and professional life. This disturbing scenario raises profound and unsettling questions about the ethical integrity and accountability within the Canadian telecommunications industry.

In the wake of my first heart attack, I returned home after several days in the hospital to recuperate. Upon my return, I received a phone call from Paul Howell, who expressed his sincere wishes for my speedy recovery. He candidly remarked that it was the worst arbitration process he had ever been involved in, noting that no arbitration would have permitted such an appalling approach had it occurred in North America. Disturbed by his account, I sent a statutory declaration to the then Minister of Communications, Michael Lee MP, detailing what Mr. Howell had disclosed. Once again, a Canadian national had courageously shone a light on the troubling events that had transpired.

Given the circumstances, venturing into the online sphere to share my story became my only viable option for exploring and exposing these critical issues between Chapters 1 and 12.

Chapter 1

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens

Chapter 2

Betrayal deceit disinformation duplicity falsehood fraud hypocrisy lying mendacity treachery and trickery. This sums up the COT government endorsed arbitrations.

Chapter 3

Ending bribery corruption means holding the powerful to account and closing down the systems that allows bribery, illicit financial flows, money laundering, and the enablers of corruption to thrive.

Chapter 4

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens. Government corruption within the public service affected most if not all of the COT arbitrations.

Chapter 5

Corruption is contagious and does not respect sectoral boundaries. Corruption involves duplicity and reduces levels of morality and trust.

Chapter 6

Anti-corruption policies need to be used in anti-corruption reforms and strategy. Corruption metrics and corruption risk assessment is good governance

Chapter 7

Bribery and Corruption happens in the shadows, often with the help of professional enablers such as bankers, lawyers, accountants and real estate agents, opaque financial systems and anonymous shell companies that allow corruption schemes to flourish and the corrupt to launder their wealth.

Chapter 8

Corrupt practices in government and the results of those corrupt practices become problematic enough – but when that corruption becomes systemic in more than one operation, it becomes cancer that endangers the welfare of the world's democracy.

Chapter 9

Corruption in government, including non-government self-regulators, undermines the credibility of that government. It erodes the trust of its citizens who are left without guidance are the feel of purpose. Bribery and Corruption is cancer that destroys economic growth and prosperity.

Chapter 10

The horrendous, unaddressed crimes perpetrated against the COT Cases during government-endorsed arbitrations administered by the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman have never been investigated.

Chapter 11

This type of skulduggery is treachery, a Judas kiss with dirty dealing and betrayal. This is dirty pool and crookedness and dishonest. This conduct fester’s corruption. It is as bad, if not worse than double-dealing and cheating those who trust you.&a

Chapter 12

Absentjustice.com - the website that triggered the deeper exploration into the world of political corruption, it stands shoulder to shoulder with any true crime story.As highlighted in the introduction to story one, the journey to publish an accurate and meticulous account of the complex events surrounding various Australian Government-sanctioned arbitrations has proven to be a formidable challenge. In this second part of the COT story, I endeavour to delve deeper into the systematic and rigorous approach that the author has been compelled to adopt. This approach seeks to substantiate the grave allegations that government public servants, who were entrusted with sensitive and classified information, may have provided privileged insider knowledge to the government-owned telecommunications carrier—referred to as the defendants.

Moreover, these public servants allegedly withheld crucial documentation from the claimants, ordinary Australian citizens who are seeking justice and accountability in a system that seems to favour powerful entities over individuals. The implications of this dynamic are significant, as it raises serious questions about the integrity and transparency of the arbitration process and the accountability of those in positions of authority. As we explore these complex issues, it is vital to consider not only the factual accuracy of events but also the broader consequences they have for those affected and for society as a whole.

Furthermore, how can the author compellingly recount the complex narrative of his inadvertent involvement in the controversial shipment of Australian wheat to a desperate, starving communist nation in China during the tumultuous 1960s? This tale gains an added layer of complexity as he and his crew of sailors stumble upon the alarming revelation that a portion of this intended humanitarian aid was being rerouted to North Vietnam—a country engaged in a brutal war against Australia, New Zealand, and the United States—providing nourishment for its troops. How can he share this morally ambiguous story without being unjustly branded a traitor by his fellow countrymen?

Did his participation in this morally ambiguous trade, which persisted even after he courageously brought to light the ethically questionable actions of government officials, play a role in the significant repercussions he endured during the arduous arbitration processes with Telstra Corporation— a company entirely owned by the government— in the 1994/95 arbitration endorsed by the government? Furthermore, could his vocal condemnation of the government’s dealings with the enemy thirty years before his arbitration have influenced the government-appointed arbitrator to downplay the legitimacy of his claims? (Refer to Flash Backs – China-Vietnam.

My presence in China was more accidental than intentional; I served as a crew member on a British tramp ship, the Hopepeak.  Our vessel was engaged in the humanitarian task of unloading Australian wheat, which we had loaded at the port of Albany in Western Australia. This shipment was not just ordinary trade; it was sent with the noble intention of alleviating hunger in the suffering nation of China. However, a significant and troubling twist emerged: some of this wheat was redirected to North Vietnam, providing sustenance to the very Vietcong forces who were at war with Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (refer to Chapter 7-Vietnam Vietcong).

Our vessel was engaged in the humanitarian task of unloading Australian wheat, which we had loaded at the port of Albany in Western Australia. This shipment was not just ordinary trade; it was sent with the noble intention of alleviating hunger in the suffering nation of China. However, a significant and troubling twist emerged: some of this wheat was redirected to North Vietnam, providing sustenance to the very Vietcong forces who were at war with Australia, New Zealand, and the United States (refer to Chapter 7-Vietnam Vietcong).

As a result, we may be left in the dark about the sheer volume of Australian wheat that found its way into the hands of the Vietcong guerrilla forces, who marched through the jungles of North Vietnam intending to slaughter and maim as many Australian, New Zealand, and USA troops as possible.

The following three statements taken from a report prepared by Australia's Kim Beasly MP on 4 September 1965 (father of Australia's former Minister of Defence Kim Beasly) only tell part of this tragic episode concerning what I wanted to convey to Malcolm Fraser, former Prime Minister of Australia when I telephoned him in April 1993 and again in April 1994 concerning Australia's wheat deals which I originally wrote to him about on 18 September 1967 as Minister for the Army.

Vol. 87 No. 4462 (4 Sep 1965) - National Library of Australia https://nla.gov.au › nla.obj-702601569

"The Department of External Affairs has recently published an "Information Handbook entitled "Studies on Vietnam". It established the fact that the Vietcong are equipped with Chinese arms and ammunition"

If it is right to ask Australian youth to risk everything in Vietnam it is wrong to supply their enemies. The Communists in Asia will kill anyone who stands in their path, but at least they have a path."

Australian trade commssioners do not so readily see that our Chinese trade in war materials finances our own distruction. NDr do they see so clearly that the wheat trade does the same thing."

How does one construct a narrative so astonishing and far-fetched that it keeps an editor awake at night, wrestling with uncertainties about its credibility until confronted with undeniable evidence that validates its authenticity? What strategies can unveil the troubling collusion between an arbitrator, a cadre of appointed watchdogs (umpires), and the defendants? How can the author expose the unsettling practice of the defendants using their sophisticated network connections to intercept and screen faxed communications emanating from his office, surreptitiously storing sensitive information without his knowledge or consent, and rerouting it to their intended destination? (Refer to Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13)

Were the defendants leveraging these intercepted documents to bolster their defence in arbitration proceedings, ultimately undermining the rightful claims of innocent claimants? How many other Australian arbitration processes have fallen victim to such covert hacking? Is this insidious practice of electronic eavesdropping—this unauthorised infiltration—still a pervasive issue in legitimate Australian arbitrations today?

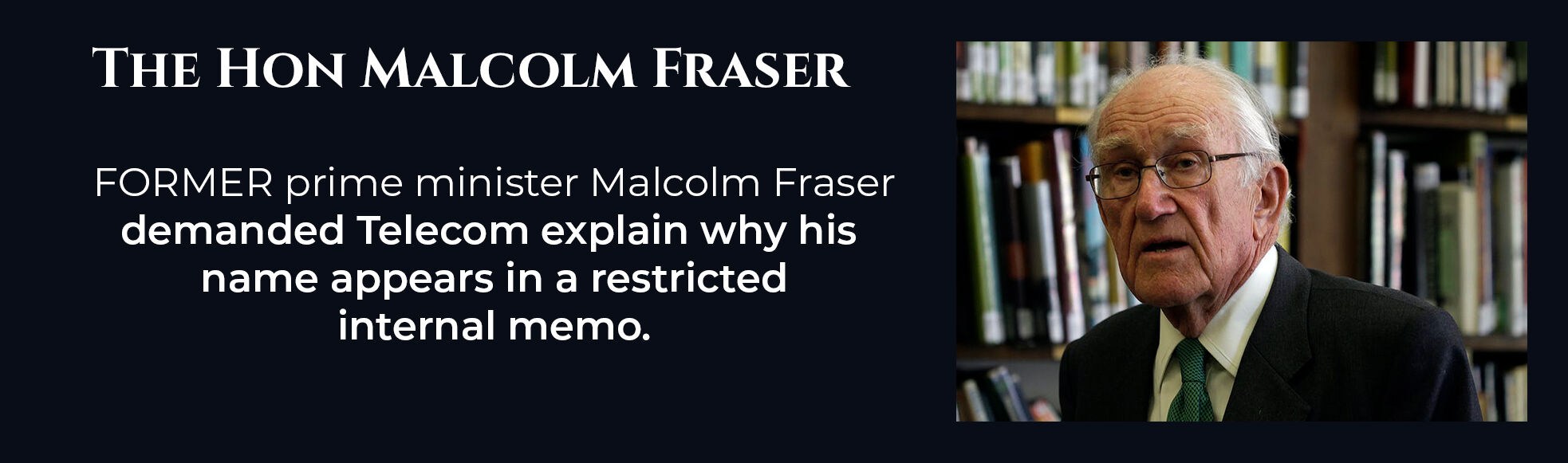

What information was removed from the Malcolm Fraser FOI released document

The AFP believed Telstra was deleting evidence at my expense

During my first meetings with the AFP, I provided Superintendent Detective Sergeant Jeff Penrose with two Australian newspaper articles concerning two separate telephone conversations with The Hon. Malcolm Fraser, former prime minister of Australia. Mr Fraser reported to the media only what he thought was necessary concerning our telephone conversation, as recorded below:

“FORMER prime minister Malcolm Fraser yesterday demanded Telecom explain why his name appears in a restricted internal memo.

“Mr Fraser’s request follows the release of a damning government report this week which criticised Telecom for recording conversations without customer permission.

“Mr Fraser said Mr Alan Smith, of the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp near Portland, phoned him early last year seeking advice on a long-running dispute with Telecom which Mr Fraser could not help.”

During the second interview conducted by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) at my business on 26 September 1994, I provided comprehensive responses to 93 questions about unauthorised surveillance and the threats I encountered from Telstra. Pages 12 and 13 from the Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1 transcripts of their second interview with me during my arbitration extensively address the threats issued by Telstra's arbitration liaison officer, Paul Rumble, and the unlawful interception of my telecommunications and arbitration-related faxes.

It is noteworthy that Paul Rumble and the arbitrator operated in collaboration. Dr. Gordon Hughes supplied Mr. Rumble with my arbitration submission materials months before Telstra should have received these documents, according to the terms of my arbitration agreement.

This situation illustrates a disregard for protocol on the part of Telstra and the individuals overseeing the various COT arbitrations. The processes involved were conducted in a manner likened to a Kangaroo Court.

What circumstances drove the arbitrator, or perhaps more intriguingly, what influences swayed him, to forward the claimant's submission to the defense on 15 June 1994? This action occurred a remarkable five months before he was legally entitled to do so, as stipulated by the arbitration agreement both parties had previously accepted. Adding to the complexity of this situation is the troubling fact that Telstra, the defendant, did not respond to the claimant's claims until 12 December 1994. This was despite the arbitration rules clearly indicating they had only one month to provide a rebuttal to the claimant's submission.

Telstra-Corruption-Freehill-Hollingdale & Page

Corrupt practices persisted throughout the COT arbitrations, flourishing in secrecy and obscurity. These insidious actions have managed to evade necessary scrutiny. Notably, the phone issues persisted for years following the conclusion of my arbitration, established to rectify these faults.

Confronting Despair

The independent arbitration consultants demonstrated a concerning lack of impartiality. Instead of providing clear and objective insights, their guidance to the arbitrator was often marked by evasive language, misleading statements, and, at times, outright falsehoods.

Flash Backs – China-Vietnam

In 1967, Australia participated in the Vietnam War. I was on a ship transporting wheat to China, where I learned China was redeploying some of it to North Vietnam. Chapter 7, "Vietnam—Vietcong," discusses the link between China and my phone issues.

A Twenty-Year Marriage Lost

As bookings declined, my marriage came to an end. My ex-wife, seeking her fair share of our venture, left me with no choice but to take responsibility for leaving the Navy without adequately assessing the reliability of the phone service in my pursuit of starting a business.

Salvaging What I Could

Mobile coverage was nonexistent, and business transactions were not conducted online. Cape Bridgewater had only eight lines to service 66 families—132 adults. If four lines were used simultaneously, the remaining 128 adults would have only four lines to serve their needs.

Lies Deceit And Treachery

I was unaware of Telstra's unethical and corrupt business practices. It has now become clear that various unethical organisational activities were conducted secretly. Middle management was embezzling millions of dollars from Telstra.

An Unlocked Briefcase

On June 3, 1993, Telstra representatives visited my business and, in an oversight, left behind an unlocked briefcase. Upon opening it, I discovered evidence of corrupt practices concealed from the government, playing a significant role in the decline of Telstra's telecommunications network.

A Government-backed Arbitration

An arbitration process was established to hide the underlying issues rather than to resolve them. The arbitrator, the administrator, and the arbitration consultants conducted the process using a modified confidentiality agreement. In the end, the process resembled a kangaroo court.

Not Fit For Purpose

AUSTEL investigated the contents of the Telstra briefcases. Initially, there was disbelief regarding the findings, but this eventually led to a broader discussion that changed the telecommunications landscape. I received no acknowledgement from AUSTEL for not making my findings public.

&am

A Non-Graded Arbitrator

Who granted the financial and technical advisors linked to the arbitrator immunity from all liability regarding their roles in the arbitration process? This decision effectively shields the arbitration advisors from any potential lawsuits by the COT claimants concerning misconduct or negligence.<

The AFP Failed Their Objective

In September 1994, two officers from the AFP met with me to address Telstra's unauthorized interception of my telecommunications services. They revealed that government documents confirmed I had been subjected to these violations. Despite this evidence, the AFP did not make a finding.&am

The Promised Documents Never Arrived

In a February 1994 transcript of a pre-arbitration meeting, the arbitrator involved in my arbitration stated that he "would not determination on incomplete information.". The arbitrator did make a finding on incomplete information.