You can access my book 'Absent Justice' here → Order Now—it's Free. It presents a compelling narrative that addresses critical societal issues related to justice and equity within Australia's arbitration and mediation processes. If you see the value in the research and evidence behind this important work, consider supporting Transparency International Australia! Your donation will help raise awareness about the injustices that impact our democracy.

Learn about the horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the seat of arbitration in Australia, as the following link suggests Chapter 11 - The eleventh remedy pursued shows. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers. Corruption, misleading, and deceptive conduct must not be practised in any shape or form. The criminal exploitation, fraud, and crookedness of Telstra and those who administered the COT arbitrations demoralised the claimants. Telstra's misrepresentation, coupled with jobbery, was clear extortion payola. The conduct of the arbitrations was a fraudulent exercise, subterfuge and an attack against the democratic process that Australia is supposed to be governed by.

How can one publish a meticulously accurate account of the events that unfolded during various Australian Government-endorsed arbitrations? What strategies does the author employ to substantiate, without risking legal repercussions, the claim that government public servants discreetly fed privileged information to the then Australian Government-owned telecommunications carrier (the defendants), while simultaneously concealing the same critical documentation from the claimants, fellow Australian citizens who deserved transparency?

By clicking on the image below, you will see that someone authorized the removal of the $250,000 liability caps outlined in clauses 25 and 26 of my arbitration agreement. Initially, my legal team, along with two Senators, reached a consensus that the arbitration agreement was equitable because the $250,000 liability caps provided me the ability to pursue legal action against the arbitration consultants for negligence. However, the abrupt removal of these critical clauses significantly impacted my situation. As a result, I lost my chance to appeal the arbitration award against the consultants, who acted with gross misconduct, leaving me without the necessary recourse to seek justice.,

How do you expose that these defendants, during the arbitration process—which was once under government ownership—used sophisticated equipment linked to their network to covertly screen faxed documents leaving your office, storing sensitive materials without your knowledge or consent, only to redirect them to their rightful destination—a route shrouded in secrecy?

Were the defendants using this intercepted material to bolster their defence during arbitration, undermining the claimants' rights?

How many other Australian arbitration processes have been victims of similar hacking tactics? Is this form of electronic eavesdropping—this insidious breach of confidentiality—still a reality during legitimate Australian arbitrations?

In January 1999, the arbitration claimants submitted a damning report to the Australian Government, detailing how confidential, arbitration-related documents were surreptitiously and illegally screened before they reached Parliament House in Canberra. Will that explosive report ever be unveiled to the Australian public, allowing citizens to grasp the full extent of these occurrences?

It is clear from AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings, specifically between points 2 and 212, that AUSTEL's use of Telstra's logbook to conduct their findings was extremely valuable, as indicated in point 209. If I had received a copy of this logbook and submitted it to the arbitrator to support my claims, the arbitrator's award would have been significantly higher. Additionally, he would not have been able to state in his award that my ongoing telephone problems were resolved early in the arbitration in July 1994.AUSTEL’s Adverse Findings,

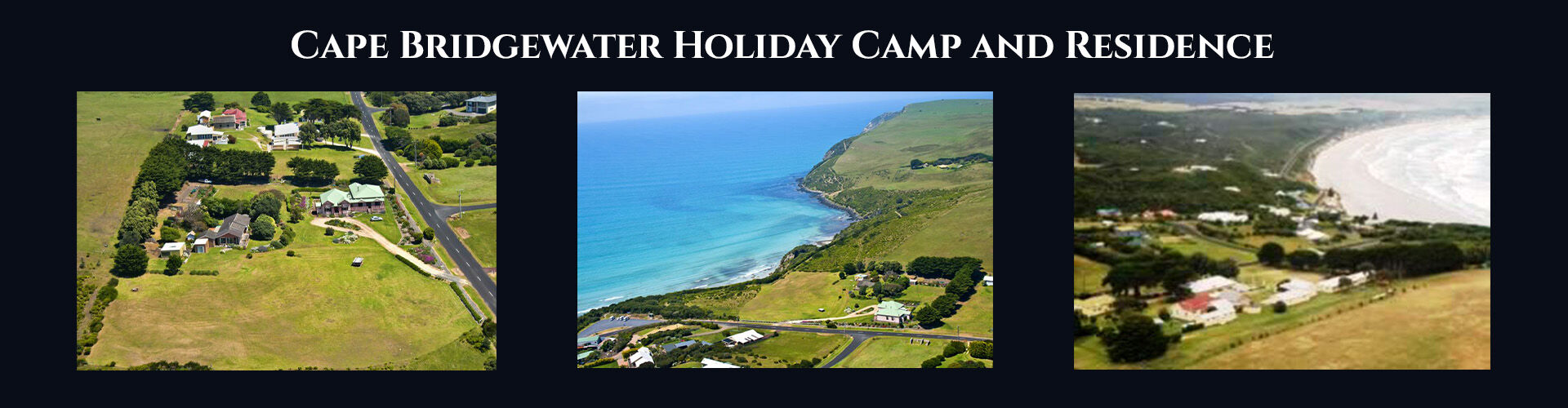

- Point 209 – “Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp has a history of service difficulties dating back to 1988. Although most of the documentation dates from 1991 it is apparent that the camp has had ongoing service difficulties for the past six years which has impacted on its business operations causing losses and erosion of customer base.”

My name is Alan Smith, and this is the story of my relentless battle against a telecommunications giant and the Australian Government. Since 1992, this conflict has taken me through the labyrinth of elected governments, various government departments, regulatory bodies, the judiciary, and the colossal telecom entity called Telstra, which was called Telecom when my saga began. I am still pursuing justice today.

My journey began in 1987 when I made a pivotal decision to leave behind my life at sea, where I had spent the better part of twenty years. I sought a new path on land that would carry me through my retirement years and beyond. Among all the enchanting places I had explored around the globe, I chose the serene yet captivating coastal region of Cape Bridgewater, located in southwest Victoria, Australia, as my new home.

My passion lies in hospitality, and I have always dreamed of running a holiday camp akin to the iconic Butlins in Bognor Regis. This place sparkled with joy during my childhood in England. Imagine my excitement when I spotted the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Convention Centre advertised for sale in The Age, a well-respected newspaper. This facility was nestled in rural Victoria, near the quaint maritime port of Portland, surrounded by stunning natural landscapes. Everything seemed to align perfectly.

To the best of my understanding, I diligently conducted my due diligence to ensure the business was financially sound. Little did I know that one crucial aspect I overlooked was checking the functionality of the phone lines.

Within just a week of taking over the business, alarm bells rang loud and clear. I received distressing calls from customers and suppliers who had made numerous attempts to reach me, only to find themselves thwarted by a dead line. Yes, here I was, tasked with managing a thriving business, yet my phone service was, at best, woefully unreliable and, at worst, completely nonexistent. As a result, we faced significant revenue losses as customers turned away in frustration.

Eight years after the conclusion of my arbitration, Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman officer Gillian McKenzie, on 28 January 2003, wrote to Telstra stating:

“Mr & Mrs Lewis claim in their correspondence attached:That they purchased the Cape Bridgewater Coastal Camp in December 2001, but since that time have experienced a number of issues in relation to their telephone service, many of which remain unresolved.

That a Telstra technician ‘Mr Tony Watson’ is currently assigned to his case, but appears unwilling to discuss the issues with Mr Lewis due to his contact with the previous camp owner, Mr Alan Smith.” (See Home-Page File No/76 and D-Lewis File 1-I)

Was there a more sinister motive involved in Telstra’s technician refusing to help Darren Lewis with the ongoing phone/fax problems that, eight years before, Telstra and the arbitrator assigned to my case failed to investigate transparently? Why was this Telstra technician still holding a grudge against me in 2002/3 because of something my 1994/95 arbitration should have addressed – i.e., the ongoing phone and facsimile problems that this same Telstra technician was refusing to help Mr Lewis with, eight years later?

And so, my quest began. Securing a dependable phone service at the property became a protracted saga filled with frustration and struggle. Along the way, I secured compensation for our business losses and encountered countless assurances that the issues were resolved. Yet, here I am, years later, still facing the same insurmountable problems. After selling the business in 2002, I learned that subsequent owners have endured similar plights (Refer to Chapter 4 The New Owners Tell Their Story and Chapter 5 Immoral - Hypocritical Conduct).

I was not alone in this battle; many independent businesspeople adversely affected by poor telecommunications joined me in my efforts. We became known as the Casualties of Telecom, or the COT cases. Our shared goal was straightforward: we wanted Telecom/Telstra to acknowledge our grievances, deliver solutions, and compensate us for our significant losses. After all, is it too much to ask for a functioning phone line?

Initially, we sought a full Senate investigation into Telecom to expose these pervasive issues. Instead, we were offered a commercial assessment process as an alternative to arbitration. This initially appeared to be a promising path toward resolution, so we gladly accepted. Yet, we were soon unceremoniously pushed out of the commercial assessment process, allowing Telstra's agreement to take precedence.

Unfortunately, that hope proved to be in vain. Almost instantaneously, doubts about the integrity of the arbitration process began to fester. We had been assured that if we entered arbitration, we would have access to the crucial Telecom documents needed to support our case. Those documents, however, were never provided, despite the promises made. To compound our frustrations, we discovered that our fax lines were illegally tapped during the arbitration process. With the considerable weight of the Government aligned against us, we found ourselves at a significant disadvantage and ultimately lost.

To make matters worse, we had unwittingly signed a confidentiality clause that significantly hampered our ability to share our experiences. I may be risking the consequences of that clause by making this information public, but I feel I have no choice—my circumstances compel me to speak out.

The next chapter of our struggle focused on our relentless pursuit of the promised documents through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests. We were confident that the evidence existed to validate our assertions that the phone lines were not functioning and had failed to meet the agreed testing protocols. However, for that evidence to be valid, we needed access to it.

Telecom engaged in a series of deceptive tactics, intercepting privileged faxes sent by COT lawyers, live-monitoring and tapping COT phones, and intercepting COT arbitration mail throughout the arbitration process. They resorted to threats against COT claimants, following through on those threats with alarming frequency. The Government had assured us that the arbitration would be straightforward, non-legalistic, and that the arbitrator could issue findings only once the issues were resolved. We were also promised access to the necessary Telecom FOI documents, yet the government-owned Telecom blatantly refused to comply. Many of the documents that were eventually provided were either defaced or irrelevant to our claims. Lacking a detailed schedule accompanying the FOIs, we wasted precious time deciphering the scant information handed over while under an unforgiving deadline.

By March 1994, during the investigation of this initiative, the Government Communications Regulator concluded that the government-owned telecommunications carrier could not locate the persistent faults plaguing my business. Alarmingly, they concealed their findings rather than sharing this critical information with the arbitrator overseeing my claim. This lack of transparency was nothing short of shocking.

It is utterly inconceivable that the Australian Government would endorse a legally binding Arbitration Agreement, supposedly drafted with independence by the President of the Australian Institute of Arbitrators. In reality, this agreement was crafted by lawyers representing the defendants—the government-owned telecommunications carrier itself. To compound matters, the Government turned a blind eye to including a clause in this agreement, designed by the defendants, that severely restricted the time available for claimants to access vital discovery documents from the defendants. These documents were essential for supporting their claims.

On page 180, ERC&A, from the official Australian Senate Hansard, dated 29 November 1994, reports Senator Ron Boswell asking Telstra’s legal directorate:

“Why did Telecom advise the Commonwealth Ombudsman that Telecom withheld FOI documents from Alan Smith because Alan Smith provided Telecom FOI documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigation?”

After receiving a hollow response from Telstra, which the senator, the AFP and I all knew was utterly false, the senator states:

“…Why would Telecom withhold vital documents from the AFP? Also, why would Telecom penalise COT members for providing documents to the AFP which substantiate that Telecom had conducted unauthorised interceptions of COT members’ communications and subsequently dealt in the intercepted information by providing that information to Telecom’s external legal advisers and others?” (See Senate Evidence File No 31)

The Australian Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) appointed a Project Manager to assist the arbitrator in navigating nine arbitrations, including mine. With the backing of his arbitration resource unit, the defendants, and the TIO, the Project Manager was empowered to scrutinise some of the most pertinent documents submitted for the arbitrations. Without notifying any of the claimants, he and his team decided which documents would be submitted to the arbitrator and which would be withheld, casting a shadow of secrecy over the proceedings.

This situation should raise serious concerns for organisations contemplating arbitration for commercial disputes in Australia or Hong Kong. The same Project Manager, now a practising arbitrator with offices in both locations, presides over such disputes. In my manuscript, "Absent Justice," I reveal how this resource unit deliberately withheld four critical documents from the arbitrator in my case. These documents had the power to alter the entire course of the arbitration and provide much-needed support to other Australian businesses grappling with similar long-standing telephone billing issues.

On November 15 1995, when the TIO sought clarification from the Project Manager regarding the missing billing claim documents, the project manager resorted to misleading and deceiving the TIO, further complicating an already convoluted process.

As my arbitration progressed, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) became aware of a chilling threat from the defendants: they would cease providing any further discovery documents if I continued to assist the AFP in their investigations into my serious complaints that those very same defendants were intercepting my phones and faxes. These discovery documents were vital to my case—I was at a standstill, unable to substantiate my arbitration claim without them.

Over the past two decades, I have meticulously gathered more than 2,230 Freedom of Information (FOI) documents, extracted from a staggering total of over 48,000 documents related to five claimants of the Compensation for Occupational Therapy (COT) scheme. Each of these 2,230 documents is carefully numbered to align with specific statements in my detailed manuscript, creating a coherent narrative supported by solid evidence. I organised this substantial work into 153 mini-reports, accessible through the clickable links labelled Evidence File-1 and Evidence-File-2. Without this concrete evidence backing my story, it would easily be dismissed as mere speculation.

From 2006 to 2018, I took the significant step of sending these files to various high-profile recipients, including the Prime Minister's office, the offices of four government ministers, the Australian Federal Police, the Victorian Police Major Fraud Group, and three pertinent government agencies. Remarkably, none of these authorities have challenged my claims or scrutinised the evidence that underpins them. Mr Neil Jepson, a barrister from the Major Fraud Group, commented that many recipients who received my submissions felt their jurisdictions did not allow them to investigate such matters. This left me perplexed. Mr Neil advised me to resubmit my evidence that the Victoria Police had been blocked from investigating to another government agency that had already indicated a refusal to look further into the issue. I went around and around in circles for eleven years with no one willing to take the Telstra Corporation to their lawyers, Freehill Hollingdale & Page, now trading as Herbert Smith Freehills Melbourne)

Given the circumstances, venturing into the online sphere to share my story became my only viable option for exploring and exposing these critical issues in chapters 1 to 12.

Chapter 1

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens

Chapter 2

Betrayal deceit disinformation duplicity falsehood fraud hypocrisy lying mendacity treachery and trickery. This sums up the COT government endorsed arbitrations.

Chapter 3

Ending bribery corruption means holding the powerful to account and closing down the systems that allows bribery, illicit financial flows, money laundering, and the enablers of corruption to thrive.

Chapter 4

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens. Government corruption within the public service affected most if not all of the COT arbitrations.

Chapter 5

Corruption is contagious and does not respect sectoral boundaries. Corruption involves duplicity and reduces levels of morality and trust.

Chapter 6

Anti-corruption policies need to be used in anti-corruption reforms and strategy. Corruption metrics and corruption risk assessment is good governance

Chapter 7

Bribery and Corruption happens in the shadows, often with the help of professional enablers such as bankers, lawyers, accountants and real estate agents, opaque financial systems and anonymous shell companies that allow corruption schemes to flourish and the corrupt to launder their wealth.

Chapter 8

Corrupt practices in government and the results of those corrupt practices become problematic enough – but when that corruption becomes systemic in more than one operation, it becomes cancer that endangers the welfare of the world's democracy.

Chapter 9

Corruption in government, including non-government self-regulators, undermines the credibility of that government. It erodes the trust of its citizens who are left without guidance are the feel of purpose. Bribery and Corruption is cancer that destroys economic growth and prosperity.

Chapter 10

The horrendous, unaddressed crimes perpetrated against the COT Cases during government-endorsed arbitrations administered by the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman have never been investigated.

Chapter 11

This type of skulduggery is treachery, a Judas kiss with dirty dealing and betrayal. This is dirty pool and crookedness and dishonest. This conduct fester’s corruption. It is as bad, if not worse than double-dealing and cheating those who trust you.&a

Chapter 12

Absentjustice.com - the website that triggered the deeper exploration into the world of political corruption, it stands shoulder to shoulder with any true crime story.

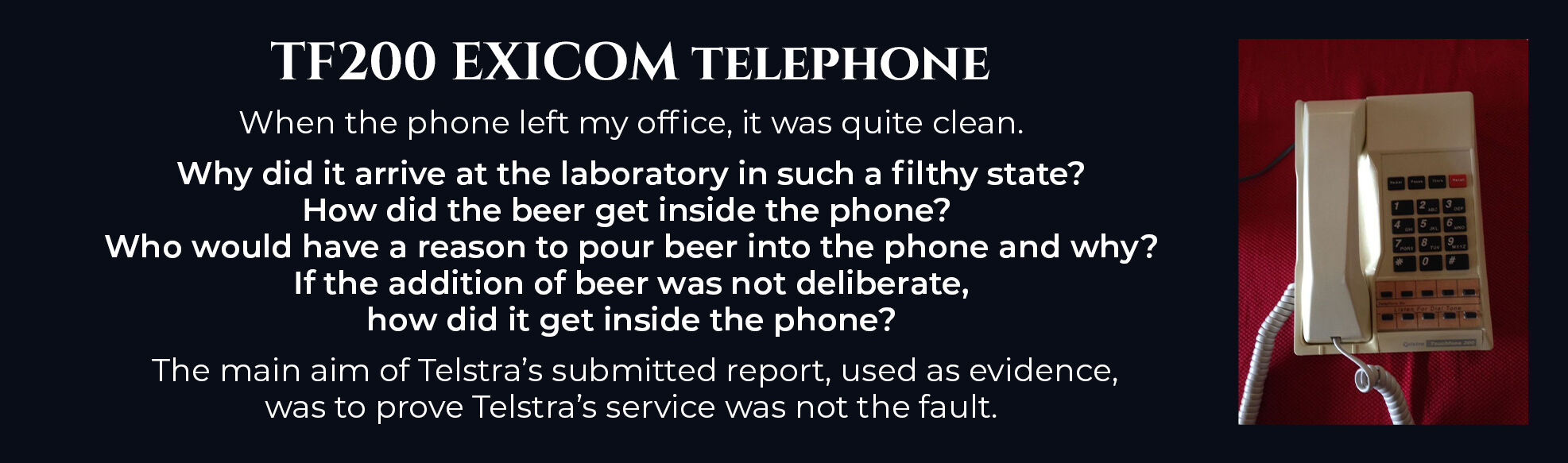

After Mr Anderson completed his testing on 27 April, the phone took nine days to reach Telstra’s laboratory. It arrived on 6 May, and laboratory testing did not commence for another four days. Ray Bell, the author of the TF 200 report, was adamant at point 1.3, under the heading Initial Inspection, that:

“The suspect TF200 telephone when received was found to be very dirty around the keypad with what appeared to be a sticky substance, possibly coffee.” (See Tampering With Evidence File No 3)

Clicking on the TF200 telephone below will show that a second photo I received under FOI was taken from the front of the same TF200 phone, confirming that the note I placed on it was pretty clean when it was received at Telstra. See Open Letter File No/37 exhibits 3, 4, 5, and 6. So, who smothered the grease over the front of the telephone after it left my business, and who poured the sticky beer residue into the same now dirty telephone, insinuating I was a hopeless drunk?

This report raises several questions. When the phone left my office, it was quite clean. Why did it arrive at the laboratory in such a filthy state? How did the beer get inside the phone? Who would have a reason to pour beer into the phone and why? If the addition of beer was not deliberate, how did it get inside the phone? The main aim of Telstra’s submitted report, used as evidence, was to prove that Telstra’s service was not at fault.

As soon as I read this beer-in-the-phone report, I requested the arbitrator, asking for a copy of all the laboratory technicians' handwritten notes so he could see how Telstra had arrived at their conclusion. I had appointed my forensic document researcher to look over the documents when I received them, and he provided me with his CV credentials and signed a confidentiality agreement stating he would not disclose his findings to anyone outside of the arbitration procedure. Although I passed all this information on to the arbitrator, the only response I received from the arbitrator and Telstra was a duplicate copy of the report I had already received as part of Telstra’s defence.

On 28 November 1995, six months after my arbitration ended, I received Telstra’s TF200 EXICOM report. This report confirms Telstra carried out two separate investigations of my EXICOM TF200 telephone, two weeks apart and the second test report, dated between 24 and 26 May 1994, proved that the first one, the report provided to the arbitrator, was not an accurate account of the testing process at all, but a total fabrication. Photos and graphs by Telstra laboratory staff proved that wet beer introduced into the TF200 phone dried out entirely in 48 hours. As mentioned above, Telstra collected my phone from my business on 27 April 1994, but it was not tested until 10 May – a gap of 14 days. Various pages (see Tampering With Evidence File No/5) confirm that, even though Telstra knew its second investigation proved the first arbitration report, dated between 10 and 12 May 1994, was more than fundamentally flawed, it still submitted the first flawed report to the arbitrator as Telstra’s factual findings.

The marked Telstra FOI documents folio A64535 to A64562 (see Tampering With Evidence File No/5), are clear evidence that Telstra did do two separate TF200 tests on my collected phone two weeks apart. FOI folio A64535 confirms with this handwritten Telstra laboratory file note, dated 26 May 1994, that when wet beer was poured into a TF200 phone, the wet substance dried up within 48 hours. The air vents within the phone itself allowed for the beer to escape. In other words, how could my TF200, collected on 27 April 1994, have been wet inside the phone on 10 May 1994 when it was tested at Telstra’s laboratories?

Another disturbing side to this tapering with arbitration evidence by Telstra is that I volunteered for the Cape Bridgewater Country Fire Authority (CFA) for many years before this tampering occurred. The following chapters show that during my arbitration, Telstra twisted the reason I could not be present for the testing of my TF200 telephone at my premises on a scheduled meeting on the morning of 27 April 1994. Telstra only reported in their file notes (later submitted to the arbitrator) that I refused to allow Telstra to test the phones because I was tired. There was no mention in these file notes that I advised the fault response unit that I had been fighting an out-of-control fire for 14 hours or that my sore eyes made it impossible to observe such testing by Telstra. I fought the fire the previous evening from 6 pm to 9 am the following morning.

It is clear from our Tampering With Evidence page that not only did Telstra set out to discredit me by implying I was just too tired to have my TF200 phone tested, but after Telstra removed the phone, it was tampered with before it arrived at Telstra’s Melbourne laboratories: someone from Telstra poured beer into the phone. In its arbitration defence report, Telstra then alleged that sticky beer was the cause of the phone’s ongoing lock-up problems, not the Cape Bridgewater network. This wicked deed and the threats I received from Telstra during my arbitration are a testament that my claims should have been investigated years ago. So, even though I carried out my civic duties as an Australian citizen, over and beyond, by supplying vital evidence to the AFP and fighting out-of-control fires, I was still penalised on both occasions during my arbitration.

The other twist to this part of my story is, how could I have spilt beer into my telephone, as Telstra's arbitration defence documents state, when I had been fighting an out-of-control fire? I certainly would not have been driving the CFA truck or assisting my fire buddies had I been drinking beer. Reading this part of my story will give the reader some idea of the dreadful conduct that we COT Cases had to put up with from Telstra as we battled for a reliable phone service.

When I provided the arbitrator and the arbitration Special Counsel with a statutory declaration prepared by Paul Westwood s forensic documents specialist, who advised he would test the collected TF200 and inspect Telstra's laboratory working notes to see how Telstra came up with their findings regarding my drinking habits had caused my phone faults and not the EXICOM TF200 both the arbitrator and arbitration special counsel refused my request to have Telstra's arbitration defence investigated on the grounds fraud had played a significant part in the preparation of the TF200 report.

Telstra-Corruption-Freehill-Hollingdale & Page

Corrupt practices persisted throughout the COT arbitrations, flourishing in secrecy and obscurity. These insidious actions have managed to evade necessary scrutiny. Notably, the phone issues persisted for years following the conclusion of my arbitration, established to rectify these faults.

Confronting Despair

The independent arbitration consultants demonstrated a concerning lack of impartiality. Instead of providing clear and objective insights, their guidance to the arbitrator was often marked by evasive language, misleading statements, and, at times, outright falsehoods.

Flash Backs – China-Vietnam

In 1967, Australia participated in the Vietnam War. I was on a ship transporting wheat to China, where I learned China was redeploying some of it to North Vietnam. Chapter 7, "Vietnam—Vietcong," discusses the link between China and my phone issues.

A Twenty-Year Marriage Lost

As bookings declined, my marriage came to an end. My ex-wife, seeking her fair share of our venture, left me with no choice but to take responsibility for leaving the Navy without adequately assessing the reliability of the phone service in my pursuit of starting a business.

Salvaging What I Could

Mobile coverage was nonexistent, and business transactions were not conducted online. Cape Bridgewater had only eight lines to service 66 families—132 adults. If four lines were used simultaneously, the remaining 128 adults would have only four lines to serve their needs.

Lies Deceit And Treachery

I was unaware of Telstra's unethical and corrupt business practices. It has now become clear that various unethical organisational activities were conducted secretly. Middle management was embezzling millions of dollars from Telstra.

An Unlocked Briefcase

On June 3, 1993, Telstra representatives visited my business and, in an oversight, left behind an unlocked briefcase. Upon opening it, I discovered evidence of corrupt practices concealed from the government, playing a significant role in the decline of Telstra's telecommunications network.

A Government-backed Arbitration

An arbitration process was established to hide the underlying issues rather than to resolve them. The arbitrator, the administrator, and the arbitration consultants conducted the process using a modified confidentiality agreement. In the end, the process resembled a kangaroo court.

Not Fit For Purpose

AUSTEL investigated the contents of the Telstra briefcases. Initially, there was disbelief regarding the findings, but this eventually led to a broader discussion that changed the telecommunications landscape. I received no acknowledgement from AUSTEL for not making my findings public.

&am

A Non-Graded Arbitrator

Who granted the financial and technical advisors linked to the arbitrator immunity from all liability regarding their roles in the arbitration process? This decision effectively shields the arbitration advisors from any potential lawsuits by the COT claimants concerning misconduct or negligence.<

The AFP Failed Their Objective

In September 1994, two officers from the AFP met with me to address Telstra's unauthorized interception of my telecommunications services. They revealed that government documents confirmed I had been subjected to these violations. Despite this evidence, the AFP did not make a finding.&am

The Promised Documents Never Arrived

In a February 1994 transcript of a pre-arbitration meeting, the arbitrator involved in my arbitration stated that he "would not determination on incomplete information.". The arbitrator did make a finding on incomplete information.