Learn about horrendous crimes, unscrupulous criminals, and corrupt politicians and lawyers who control the legal profession in Australia. Shameful, hideous, and treacherous are just a few words that describe these lawbreakers.Instances of foreign bribery, foreign corrupt practices, kleptocracy, foreign corruption programs, absentjustice.com - the website that triggered the deeper exploration into the world of political corruption, it stands shoulder to shoulder with any true crime and international fraud against the government present significant challenges.

Until the late 1990s, the Australian government was the sole owner of Telecom, which served as the country's primary telephone network and communications carrier. This entity, now privatized and known as Telstra, historically held a monopoly over telecommunications in Australia. As a result of this monopoly, Telecom neglected the maintenance and development of its infrastructure, leading to significant deterioration and unsatisfactory service quality.

In a particularly troubling situation, four small business owners faced severe communication problems that severely impacted their operations. Frustrated and without recourse, they were compelled to enter into arbitration with Telstra in order to seek resolution for their grievances. Unfortunately, the arbitration process was fundamentally flawed. The appointed arbitrator demonstrated a bias towards Telstra, actively minimising the claims and losses presented by the Casualties of Telstra (COT) members. Instead of facilitating a fair process, the arbitrator allowed Telstra to effectively control the arbitration, undermining any hope for a just outcome.

Compounding these issues, Telstra was reportedly involved in serious misconduct during the arbitration proceedings. Despite the gravity of these actions, neither the Australian government nor the Australian Federal Police has yet held Telstra or any of the other parties implicated in this deception accountable for their actions. This raises a troubling question: why does it appear that Telstra operates above the law, seemingly immune to the consequences of its actions?

What unfolds in the twelve chapters below is not merely a tale, but a meticulous dissection of treachery that resonates with the dark undercurrents of corruption running through the COT Cases. By delving into separate sections, as done in Evidence File-1 and Evidence-File-2, we sought to ensure that no fragment of truth about these insidious practices would be lost to the shadows. Who could fathom that the very arbitrator dealing with these cases would permit the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman to wield falsehoods about his own wife, subsequently passing these deceitful claims to the Institute of Arbitrators Australia? This sinister manoeuvre served to prevent the Institute's President from launching a necessary investigation into the arbitrator’s questionable actions.

In a similar vein, the government regulator’s collusion came to light, conveniently obscuring the distress of nearly 120,000 Telstra customers plagued by similar COT-type phone faults. Telstra, in a chilling display of power, compelled the government to remove these alarming findings from its report. Instead, the arbitrator was misled into believing there were only a handful—approximately 50 or more —COT-type phone faults, as the following link starkly reveals → Chapter 1 - Can We Fix The CAN.

And yet, the depths of this conspiracy ran even deeper. In our endeavour to uncover the entire narrative, we were driven to expand the twelve chapters already written, crafting an additional twelve, all to illuminate a chilling saga that remains incomplete. The collusion within the Australian Establishment is staggering, and it is through this painstaking effort that we strive to unveil the appalling assaults aimed at twenty-one Australians—assaults designed to obscure the grim reality of Australia’s telecommunications system.

It is chillingly sinister that Telstra, the defendant in this affair, orchestrated a manipulative scheme that led the government regulator to drastically alter the findings of the AUSTEL report released on April 13, 1994. This crucial document callously brushed aside the devastating struggles of 120,000 ordinary Australian citizens—individuals ensnared in COT-type problems, suffering through severe service interruptions and baffling billing discrepancies. The Department of Communications, Information Technology, and the Arts (DCITA) disgracefully cherry-picked data from this deeply compromised report, deliberately undermining the legitimacy of the COT claims and turning a blind eye to the distress of countless victims.

The AS 639 File AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647, deceptively titled “Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts – Casualties of Telstra (COT) Background and Information for Minister's Office,” was weaponised by the government during my assessment process from March to April 2006. This insidious document not only omits the 212 critical points I raised in Document 1659 but also fails to acknowledge that the government regulator AUSTEL found in my favour on March 3, 1994, as their Cape Bridgewater Holiday Report blatantly reveals. Shockingly, this vital report was concealed from me until November 2007—thirteen long years after the arbitrator recklessly issued his findings without ever addressing my ongoing telephone issues.

Furthermore, the AS 639 File conveniently ignores the fact that AUSTEL (now known as ACMA) was fully aware of all these critical details six weeks before I unwittingly signed my arbitration agreement on April 21, 1994. Yet, knowing this, AUSTEL callously permitted me to squander thirteen months and over $300,000 in arbitration fees in a futile attempt to prove something they had already established long before my arbitration began. This is nothing short of a betrayal, revealing a treacherous web of deceit and corruption that has irreparably damaged my life.

Dear Mr Smith,

"Casualties of Telstra - lndependent Assessment"

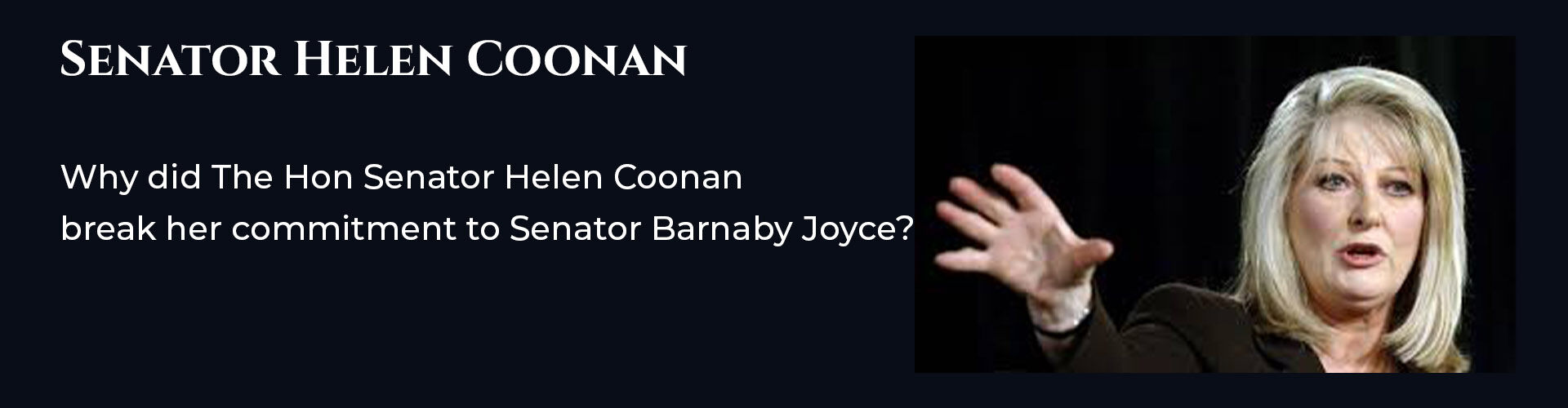

“As a result of my thorough review of the relevant Telstra sale legislation, I proposed a number of amendments which were delivered to Minister Coonan. In addition to my requests, I sought from the Minister closure of any compensatory commitments given by the Minister or Telstra and outstanding legal issues. …”

“I am pleased to inform you that the Minister has agreed there needs to be finality of outstanding COT cases and related disputes. The Minister has advised she will appoint an independent assessor to review the status of outstanding claims and provided a basis for these to be resolved.”

“I would like you to understand that I could only have achieved this positive outcome on your behalf if I voted for the Telstra privatisation legislation.” (Senate Evidence File No 20)

My name is Alan Smith, and my story is one of unyielding perseverance in the face of an overwhelming telecommunications giant and the shadowy forces within the Australian Government. This tumultuous journey has unfolded across the intricate landscape of power, regulatory bodies, and the judiciary, all centred around the colossal entity known as Telstra—formerly Telecom—since 1992. What began as a quest for justice has been marred by a tapestry of deception and betrayal, a struggle that persists to this day, leaving scars that refuse to heal.

My story traces back to 1987, a year that marked the end of my 26-year life at sea—a life filled with the salt and spray of the ocean and adventures that shaped my character. Yearning for stability and a fresh start, I cast my gaze towards Australia. This land promised opportunity and possibility, utterly unaware of the pervasive corruption that lay waiting below the surface.

With a passion for hospitality and a dream to foster joy in a nurturing environment for children, I set my sights on running a school holiday camp. My heart raced with excitement when I discovered the Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp and Convention Centre, a charming property advertised in The Age newspaper. Nestled amidst the breathtaking rural landscape of Victoria, near the tranquil port town of Portland, the camp seemed like a slice of paradise, rich with potential. I meticulously reviewed every detail, conducting diligent research to ensure the success of my new venture. Yet, in my eagerness, I tragically overlooked one critical factor: the phone lines' functionality.

Just a week after acquiring the business, the stark reality struck me like a thunderclap. My establishment had become enshrined in a communication black hole; customers and suppliers were unable to reach me, and as the phone remained silent, the whispers of business faded away. My dreams evaporated, lost amidst the chaos and uncertainty of a broken phone service. What began as a desperate scramble for survival soon morphed into a fervent quest for justice.

What unfolded was a nightmarish labyrinth of deceit and obfuscation. The simple request for a working phone escalated into an overwhelming struggle against a faceless bureaucracy that seemed determined to ignore my plight. Promises of compensation for my crippling losses trickled in, but they were buried beneath a mountain of bureaucratic red tape that served only to prolong my agony. Even after I relinquished ownership of my business in 2002, the new owners were thrust into the same harrowing scenario, a testament to the deep-rooted issues that had plagued the establishment.

I was not alone in my distress. A coalition of independent business owners, collectively known as the Casualties of Telecom—or the COT cases—joined me in my fight for recognition and accountability. Together, we fervently sought acknowledgement of our suffering from Telstra, only to face an unforgiving wall of indifference and callousness. “Fix the problems!” we implored, “And compensate us for our immeasurable losses!” After all, is it too much to ask for a functional phone line, the very lifeline of our businesses?

Our fervent appeals for a comprehensive Senate investigation were nonchalantly brushed aside, replaced by a disheartening arbitration process that initially seemed promising. Naively, we accepted this path, drawn by the tantalising prospect of resolution. Yet, our optimism quickly wilted in the face of reality. The essential documents promised by Telecom and the government that owned it, critical for substantiating our claims, never materialised. Instead, we uncovered the chilling truth that our communications were being covertly intercepted—an insidious violation that hinted at conspiracy and collusion.

The fax imprint across the top of this letter dated 12 May 1995 (Open Letter File No 55-A) is the same as the fax imprint described in the 7 January 1999 Scandrett & Associates report provided to Senator Ron Boswell (see Open Letter File No/12 and File No/13), confirming faxes were intercepted during the COT arbitrations. One of the two technical consultants attesting to the validity of this January 1999 fax interception report emailed me on 17 December 2014, stating:

“I still stand by my statutory declaration that I was able to identify that the incoming faxes provided to me for review had at some stage been received by a secondary fax machine and then retransmitted, this was done by identifying the dual time stamps on the faxes provided.” (Front Page Part One File No/14)

It is clear from exhibits 646 and 647 (see AS-CAV Exhibits 589 to 647) that Telstra admitted in writing to the Australian Federal Police on 14 April 1994 that my private and business telephone conversations were listened to and recorded over several months, but only when a particular officer was on duty.

Does Telstra really expect the AFP to accept that every time this officer left the Portland telephone exchange, the alarm — a sinister device meant to broadcast my private conversations — was conveniently turned off? What was the purpose of installing such intrusive equipment on my telephone lines if it was only operational while this individual was on duty? When I demanded, under the FOI Act during my arbitration, that Telstra provide all the detailed data from this covert setup tailored explicitly for their Portland technician, they withheld crucial information not just in my 1994.95 arbitration but continue to do so in 2025.

On my second request for the elusive data, Paul Rumble, Telstra's arbitration officer, resorted to veiled threats. He warned me that if I continued to share this information with the AFP, Telstra would cut off access to their so-called 'support.' It was a clear ultimatum: stop sharing FOI documents, and they would graciously assist me in supplying 'evidence' to the arbitrator. I refused to be intimidated by their corrupt machinations.

Why did it become the responsibility of Senator Ron Boswell to question Telstra?

“Why did Telecom notify the Commonwealth Ombudsman that it intentionally withheld Freedom of Information (FOI) documents from Alan Smith, citing his provision of documents to the Australian Federal Police during their investigative proceedings?”

After receiving a vague and unsatisfactory answer to this pressing inquiry, what compelled the Senator to confront Telstra once more → (Senate Evidence File No 31)?

“…Why would Telecom choose to withhold essential documents from the AFP, an agency tasked with upholding the law? Additionally, why would Telecom impose penalties on COT members for supplying critical evidence to the AFP that substantiated claims of unauthorized interceptions of their communications? It is particularly concerning that Telecom not only intercepted these communications but also shared the sensitive information obtained with its external legal advisers and other parties."

Most troubling of all, why didn’t the arbitrator take the initiative to consult with the Supreme Court, seeking intervention to halt such unethical conduct upon realising that the threats had been executed?

During the chilling second interview on 26 September 1994, conducted by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) at my business, a staggering 93 questions were hurled at me, a calculated interrogation that served their dark agenda regarding the bugging scandal, formally documented as Australian Federal Police Investigation File No/1). The transcripts on pages 12 and 13 reveal a shocking truth: I named Paul Rumble as the orchestrator behind the menacing threats that loomed over us.

My 3 February 1994 letter to Michael Lee, Minister for Communications (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-A) and a subsequent letter from Fay Holthuyzen, assistant to the minister (see Hacking-Julian Assange File No/27-B), to Telstra’s corporate secretary, show that I was concerned that my faxes were being illegally intercepted.

An internal government memo, dated 25 February 1994, confirms that the minister advised me that the Australian Federal Police (AFP) would investigate my allegations of illegal phone and fax interception. (See Hacking-Julian Assange File No/28).

How do you expose that these defendants, during the arbitration process—which was once under government ownership—used sophisticated equipment linked to their network to covertly screen faxed documents leaving your office, storing sensitive materials without your knowledge or consent, only to redirect them to their rightful destination—a route shrouded in secrecy?

Were the defendants using this intercepted material to bolster their defence during arbitration, undermining the claimants' rights?

Leading up to the signing of the COT Cases arbitration, on 21 April 1994, AUSTEL wrote to Telstra on 10 February 1994 stating:

“Yesterday we were called upon by officers of the Australian Federal Police in relation to the taping of the telephone services of COT Cases.

“Given the investigation now being conducted by that agency and the responsibilities imposed on AUSTEL by section 47 of the Telecommunications Act 1991, the nine tapes previously supplied by Telecom to AUSTEL were made available for the attention of the Commissioner of Police.” (See Illegal Interception File No/3)

How many other Australian arbitration processes have been victims of similar hacking tactics? Is this form of electronic eavesdropping—this insidious breach of confidentiality—still a reality during legitimate Australian arbitrations?

With the government providing only nominal support, our evidence shrouded in secrecy, and our pleas for investigation very systematically dismissed, the odds continued to mount against us. The most insidious betrayal, however, lay in a confidentiality clause we unwittingly signed, effectively binding us in silence while they wielded their power unchecked. Now, as I contemplate risking that confidentiality to share my story, I am left to ponder the extent of my remaining options.

The Secret State

On 26 September 2021, Bernard Collaery, Former Attorney-General of the Australian Capital Territory (under the heading) The Secret State, The Rule of Law & Whistleblowers, at point 7 of his 12-page paper, noted:

"On some significant issues the Australian Parliament has ceased to be a place of effective lawmaking by the people, for the people. It has become commonplace for Parliamentarians to see a marathon superannuated career out with ideals sacrificed for ambition."

Perhaps the best way to expose this part of the COT story is to use the Australia–East Timor spying scandal, which began in 2004 when an electronic covert listening device was clandestinely planted in a room adjacent to East Timor (Timor-Leste) Prime Minister's Office at Dili, to covertly obtain information to ensure the Liberal Coalition Government held the upper hand in negotiations with East Timor over the rich oil and gas fields in the Timor Gap. The East Timor government stated that it was unaware of the espionage operation undertaken by Australia.

This website showcases the compelling stories of whistleblowers, who are celebrated for their unwavering dedication to justice for all. At the onset of my narrative, it is crucial to introduce Bernard Collaery, the former Attorney-General of the Australian Capital Territory. His story resonates deeply with mine, as it mirrors the experiences shared in the COT Cases, where our telephone lines were subjected to relentless hacking for several years, both before and potentially during our arbitration process. The government had endorsed this arbitration as a fair method for resolving our disputes, yet the troubling reality was far more complex.

The gravity of the situation becomes even more pronounced when considering the evidence that Bernard Collaery uncovered while negotiating on behalf of his clients, the Timor-Leste Government. In a similar vein, the arbitration faxes involved in the COT Cases were not only vulnerable but actively intercepted during their transmission. A covertly installed secondary fax machine within Telstra's network would capture sensitive information, duplicate it, and then relay it to the intended recipient. This elaborate scheme underscores the lengths to which some entities will go to manipulate data and undermine trust in the pursuit of justice.

Our odyssey pressed on through the convoluted maze of Freedom of Information requests, a desperate, Sisyphean attempt to unearth the buried documents. The years from 1994 to 2011 were characterised by a grotesque dance with bureaucracy, filled with frustration and despair. In May 2011, I faced my final battle before the Administrative Appeals Tribunal in Melbourne, my hopes shattered by the shadowy machinations of the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). The government solicitors stood united against us, and once again, I found myself facing defeat.

In the wreckage of my dreams, the question loomed: what options remained? We had already lost our legacy in the arbitration process, our failures compounded by lost appeals and a devastated business. As I stood amidst the ashes of my once-thriving enterprise, a startling revelation came to light. On June 3, 1993, Telstra executives had visited my business, inadvertently leaving behind an open briefcase that, unbeknownst to them, held vital insights. Inside was a file marked "Cape Bridgewater Holiday Camp," which confirmed that they had been aware of my struggles all along, while I had been deliberately misled.

Had I shared the crucial documents with the media that I had previously submitted to AUSTEL, the government communications regulator, the ensuing pressure from the press might have compelled Telstra and the government to confront and rectify my ongoing issues. Instead, AUSTEL conspired to obscure the truth surrounding my telecommunications troubles, a complicity echoed by the arbitrator’s effort to bury my claims deep within the bureaucratic trenches, ensuring that my voice would remain unheard and my suffering unrecognised.

What unfolded in those darkened rooms was an orchestrated charade of arbitration. The chosen arbiter, a mere puppet in Telstra's grand performance, distorted reality to favour the corporation, minimising our claims and systematically silencing our losses.

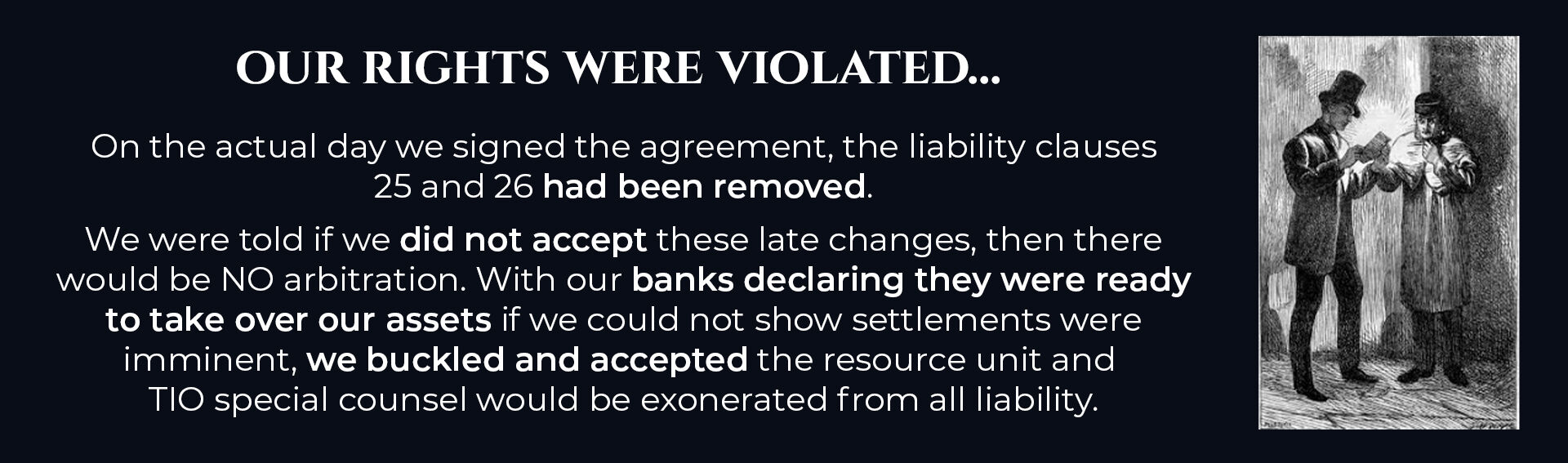

By clicking on the image below, you will unearth a sinister plot: someone with nefarious intent has clandestinely authorised the alteration of clause 24 and the ruthless removal of the $250,000 liability caps embedded in clauses 25 and 26 of my arbitration agreement. Initially, my legal team, alongside two Senators, had uneasily concluded that the arbitration agreement was just; those liability caps had been my crucial legal lifeline to hold the arbitration consultants accountable for their negligence. However, in a shocking manoeuvre steeped in deceit, these essential clauses were stripped away, leaving me vulnerable, exposed, and powerless to challenge the arbitration award against the consultants responsible for appalling misconduct. The dark consequences of this betrayal have plunged me into a desperate struggle for justice, robbed of the recourse I desperately need against the overwhelming tide of corruption that seeks to silence me.

This insidious web of deception appears to have been meticulously orchestrated to sabotage the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, obstructing any effort to investigate Dr. Hughes's misconduct—misconduct that marred the very foundation of the arbitration process and tainted my own harrowing experience. The narrative unfolds within shadowy corridors, where clandestine meetings weave a complex tapestry of biased decisions that blatantly favour the government-owned Telstra Corporation. Behind closed doors, only Telstra’s representatives lurked, while the arbitrator and administrative umpires engaged in a sinister dance of secrecy, exposing the unsettling alliances of power and influence that corroded the essence of justice.

It is crucial to unveil the stark reality behind the arbitration agreement that ensnared the three COT cases: Ann Garms, Grahan Schorer, and me. We were compelled to sign a document riddled with deceit, a sophisticated trap intricately designed to serve the interests of the very industry from which we sought justice.

What is even more egregious is his audacious attempt, after exiting the arbitration arena to join KPMG as a partner, to mislead the second appointed arbitration administrator, John Pinnock, in a September 15, 1995, correspondence. He brazenly claimed that all my billing claim documents had been addressed, but this was nothing more than a treacherous facade designed to obscure the truth. Such actions not only undermine the arbitration process but also raise serious questions about the motivations behind them.

Fast forward to 2025, and this same individual, now exonerated from all liability, John Rundell, runs two arbitration centres—one lurking in Melbourne and the other shadowy in Hong Kong.

This raises a deeply troubling question: if he was unscrupulous enough to deceive and mislead during my arbitration (Refer to Chapter 1 - The Collusion Continues and Chapter 2 - Inaccurate and Incomplete), what guarantees exist that he hasn’t perpetuated this pattern in the arbitration centres he now oversees? The implications of such manipulation are deeply unsettling and challenge the very foundation of these institutions. How many other times has he distorted the truth in his operational dealings? It’s a sinister thought that erodes trust in the arbitration process as a whole.

Even more alarming, as detailed on this homepage, are the corrupt practices that undermined three out of four arbitrations, including mine. These practices expose the treachery surrounding the arbitration agreement, which the government endorsed. During a two-day discussion process, the confidentiality agreement—specifically clauses 24, 25, and 26—was illicitly altered. What was supposed to be a transparent negotiation devolved into a sinister game as lawyers representing the claimants, alongside government officials, were duped into agreeing to a set of clauses that were ultimately changed and modified after their approval. These newly crafted clauses shielded the arbitration consultants appointed by the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) from accountability for their misconduct, thus robbing me of the opportunity to appeal my award.

This gross misconduct, marked by the willful concealment of five vital letters dated between October 4, 1994, and December 16, 1994—attached here as (File, 46-F, 46-G, 46-H, 46-I and 46-J → Open letter File No/46-A to 46-l)—remained hidden from both the arbitrator and me throughout the arbitration process. Now, in 2025, nearly three decades after this unlawful act, the TIO-appointed consultants have yet to face any consequences for their treachery. This pervasive culture of corruption must be exposed and eradicated. Why didn't Dr Hughes force Telstra to fix my ongoing phone and faxing problems, as he was supposed to do as part of the AUSTEL-facilitated process, which states in their COT Cases Report of April 1993, would be the case?

After concluding my arbitration on May 11, 1995, I found that it did not address my claims regarding ongoing issues with telephone and fax communication. Law Partners Melbourne advised me to seek all my pre-arbitration materials, which the arbitration process may have sent but were not received by my office due to the ongoing fax problems. Once we obtain this "Arbitration File", we can assess whether there is reasonable cause to appeal the arbitration process.

The arbitrator's office refused to provide the "Arbitration File", citing no reason for not supplying it. Between 18 October 1995 and 4 October 1997, with the assistance of Mr John Wynack, Director of Investigations on behalf of the Commonwealth Ombudsman, I sought, under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act, from Telstra a copy of their "Arbitration File." The various letters attached confirm that Mr Wynack did not believe Telstra’s claim that it destroyed the file → Home Page File No/82

Since the Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman (TIO) was the administrator of my arbitration, and given that the arbitration agreement signed by all parties acknowledged that the TIO would receive a copy of all arbitration materials, I also reached out to John Pinnock, the second appointed TIO, for assistance.

John Pinnock’s letter of 10 January 1996, in response to that request for my "Arbitration File", states:

“I refer to your letter of 31 December 1996 in which you seek to access to various correspondence held by the TIO concerning the Fast Track Arbitration Procedure. …

“I do not propose to provide you with copies of any documents held by this office.” (See Open Letter File No 57-C)

I wrote to Laurie James, President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, to express my concerns that the arbitration process had not been conducted in accordance with our agreed-upon procedures. I also highlighted that the ongoing issues I was experiencing with my telephone and fax services, which were the reasons I initiated the arbitration, had not been resolved. These problems were intended to be addressed as part of my arbitration, as per the commitment from AUSTEL, the Australian Communications Authority. Yet, they continued to impact my business as of December 1995.

On 23rd January 1996, Dr Hughes writes to John Pinnock, re Laurie James, and notes: -

“I enclose copy letters dated 18 and 19 January 1996 from the Institute of Arbitrators Australia. I would like to discuss a number of matters which arise from these letters, including:

- the cost of responding to the allegations;

- the implications to the arbitration procedure if I make a full and frank disclosure of the facts to Mr James. (File 205 AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233)-

What sinister and treacherous undercurrents could be twisting the arbitration process, compelling Dr. Hughes to withhold crucial information from Mr. James? This disturbing scenario raises deeply unsettling questions about the integrity of a procedure I meticulously outlined to Laurie James—specifically, how Dr. Hughes blatantly ignored the ethical obligations to carry out my arbitration in line with the promises made to the claimants.

Why did he choose to conceal pivotal details, especially the alarming fact that he had previously warned Mr. Pinnock's predecessor, Warwick Smith, on May 12, 1995, that the arbitration agreement was not just flawed, but fundamentally corrupt, desperately in need of overhaul? Yet, he opted to employ this broken system to make a hasty determination on my claim, rushing to deliver a legal paper in grease the very next day after concluding my arbitration. These egregious omissions suggest a more insidious agenda at play, hinting at collusion and malfeasance that cast a dark shadow over the legitimacy and fairness of the entire arbitration process. The layers of deceit and manipulation raise a chilling spectre of betrayal, painting a picture of a system rotten to its core, where ethics are sacrificed on the altar of convenience and hidden motives.

Why did he choose to conceal pivotal details, especially the alarming fact that he had previously warned Mr. Pinnock's predecessor, Warwick Smith, on May 12, 1995, that the arbitration agreement was not just flawed, but fundamentally corrupt, desperately in need of overhaul → (Open Letter File No 55-A)? Yet, he opted to employ this broken system to make a hasty determination on my claim, rushing to deliver a legal paper in grease the very next day after concluding my arbitration. These egregious omissions suggest a more insidious agenda at play, hinting at collusion and malfeasance that cast a dark shadow over the legitimacy and fairness of the entire arbitration process. The layers of deceit and manipulation raise a chilling spectre of betrayal, painting a picture of a system rotten to its core, where ethics are sacrificed on the altar of convenience and hidden motives.

On 27 February 1996, John Pinnock, the second Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman and the appointed administrator of my arbitration, sent a letter to Laurie James, the President of the then Institute of Arbitrators Australia, with an insidious agenda: to undermine my credibility. In a calculated move, the TIO falsely informed Mr. James that I had made a late-night call to the arbitrator’s wife at 2 AM, a blatant fabrication designed to tarnish my reputation. This deliberate misinformation revealed a disturbing willingness to manipulate the truth for their own purposes (Refer to Chapter 4 - The Seventh Damning Letter).

“Mr Smith has admitted to me in writing that last year he rang Dr Hughes’ home phone number (apparently in the middle of the night, at approximately 2.00am) and spoke to Dr Hughes’ wife, impersonating a member of the Resource Unit.” (File 209 - AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233)

PLEASE NOTE: If I had written to the TIO, as he suggests in his letter to Laurie James, why didn't he provide a copy of my letter?

On 26 September 1997, nineteen months after at John Pinnock (Telecommunications Industry Ombudsman) and Dr Gordon Hughes (the arbitrator to my case) had between them deliberately misinformed Laurie James concerning my claims to Mr James that my arbitration had not been conducted under the ambit of the arbitration agreement (the rules agreed to before we four COT Cases signed our arbitration agreement) Mr Pinnock, under oath formally addressed a Senate estimates committee refer to page 99 COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA - Parliament of Australia and Prologue Evidence File No 22-D), noting,

“In the process leading up to the development of the arbitration procedures – the claimants were told clearly that documents were to be made available to them under the FOI Act.

“Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, the arbitrator had no control over that process, because it was a process conducted entirely outside the ambit of the arbitration procedures.”

In the context of our arbitrations, which were ostensibly conducted under the esteemed authority of the Supreme Court of Victoria, a troubling question arises: why did Dr. Gordon Hughes fail to disclose to the Court that he had no control over the coercive threats being perpetrated by Telstra as acknowledge in Senate Hansard dated 29 November 1994 → Senate Evidence File No 31? This omission suggests a disregard for transparency and raises serious concerns about the integrity of the entire arbitration process. Such a lack of communication implies that the COT Cases were not merely mismanaged but were conducted in a manner that may be perceived as both sinister and corrupt, operating outside the established protections and principles outlined in the Arbitration Act. This troubling reality raises questions about the legitimacy of the outcomes and the ethical conduct of those involved in the proceedings.

After John Pinnock's unsettling acknowledgement to the Senate Committee that the arbitration process was not only flawed but skewed from the very start, my claim—brought to the attention of Laurie James, President of the Institute of Arbitrators Australia, nearly two years ago—was unequivocally validated. So, why did Pinnock remain silent and fail to advise the government to reopen my arbitration process, allowing me to amend my claim? This deliberate inaction by Pinnock and Dr. Hughes has cost my partner, Cathy, and me twenty-eight years of our lives, shackling us to the weight of these grotesque injustices. Their treachery has ensured that we live in a reality stained by corruption, a reality that could have been entirely different.

The chilling reality that John Pinnock's letter to Laurie James was copied 'Cc'd' to Dr Gordon Hughes, as the letter shows, (→ (File 209 - AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233) reveals the depths of their collusion, indicating a desperate need for both him and Dr. Hughes to face public scrutiny for their long-standing cover-up. The deceit embedded in John Pinnock's twisted letter to Laurie James is nothing short of sinister, especially considering that both he and Dr. Gordon Hughes were aware that I never made a call to Dr. Hughes' wife at the unholy hour of 2:00 AM, as the letter deceitfully claims. This flagrant manipulation of the truth underscores a diabolical partnership aimed at silencing me and concealing their despicable misconduct.

The chilling reality that John Pinnock's letter to Laurie James was copied 'Cc'd' to Dr Gordon Hughes, as the letter shows, (→ (File 209 - AS-CAV Exhibit 181 to 233) reveals the depths of their collusion, indicating a desperate need for both him and Dr. Hughes to face public scrutiny for their long-standing cover-up. The deceit embedded in John Pinnock's twisted letter to Laurie James is nothing short of sinister, especially considering that both he and Dr. Gordon Hughes were aware that I never made a call to Dr. Hughes' wife at the unholy hour of 2:00 AM, as the letter deceitfully claims. This flagrant manipulation of the truth underscores a diabolical partnership aimed at silencing me and concealing their despicable misconduct.

The continuation of this Home page can be accessed by clicking on Not Fit For Purpose in the following 12 chapters.

Telstra-Corruption-Freehill-Hollingdale & Page

Corrupt practices persisted throughout the COT arbitrations, flourishing in secrecy and obscurity. These insidious actions have managed to evade necessary scrutiny. Notably, the phone issues persisted for years following the conclusion of my arbitration, established to rectify these faults

Confronting Despair

The independent arbitration consultants demonstrated a concerning lack of impartiality. Instead of providing clear and objective insights, their guidance to the arbitrator was often marked by evasive language, misleading statements, and, at times, outright falsehoods.

Flash Backs – China-Vietnam

In 1967, Australia participated in the Vietnam War. I was on a ship transporting wheat to China, where I learned China was redeploying some of it to North Vietnam. Chapter 7, "Vietnam—Vietcong," discusses the link between China and my phone issues.

A Twenty-Year Marriage Lost

As bookings declined, my marriage came to an end. My ex-wife, seeking her fair share of our venture, left me with no choice but to take responsibility for leaving the Navy without adequately assessing the reliability of the phone service in my pursuit of starting a business.

Salvaging What I Could

Mobile coverage was nonexistent, and business transactions were not conducted online. Cape Bridgewater had only eight lines to service 66 families—132 adults. If four lines were used simultaneously, the remaining 128 adults would have only four lines to serve their needs.

Lies Deceit And Treachery

I was unaware of Telstra's unethical and corrupt business practices. It has now become clear that various unethical organisational activities were conducted secretly. Middle management was embezzling millions of dollars from Telstra.

An Unlocked Briefcase

On June 3, 1993, Telstra representatives visited my business and, in an oversight, left behind an unlocked briefcase. Upon opening it, I discovered evidence of corrupt practices concealed from the government, playing a significant role in the decline of Telstra's telecommunications network.

A Government-backed Arbitration

An arbitration process was established to hide the underlying issues rather than to resolve them. The arbitrator, the administrator, and the arbitration consultants conducted the process using a modified confidentiality agreement. In the end, the process resembled a kangaroo court.

Not Fit For Purpose

AUSTEL investigated the contents of the Telstra briefcases. Initially, there was disbelief regarding the findings, but this eventually led to a broader discussion that changed the telecommunications landscape. I received no acknowledgement from AUSTEL for not making my findings public.

&am

A Non-Graded Arbitrator

Who granted the financial and technical advisors linked to the arbitrator immunity from all liability regarding their roles in the arbitration process? This decision effectively shields the arbitration advisors from any potential lawsuits by the COT claimants concerning misconduct or negligence.<

The AFP Failed Their Objective

In September 1994, two officers from the AFP met with me to address Telstra's unauthorised interception of my telecommunications services. They revealed that government documents confirmed I had been subjected to these violations. Despite this evidence, the AFP did not make a finding.&am

The Promised Documents Never Arrived

In a February 1994 transcript of a pre-arbitration meeting, the arbitrator involved in my arbitration stated that he "would not determination on incomplete information.". The arbitrator did make a finding on incomplete information.

If revealing actions that harm others is viewed as morally unacceptable, why do governments encourage their citizens to report such crimes and injustices? This contradiction highlights an essential aspect of civic duty in a democratic society. When individuals bravely expose wrongdoing, they often earn the title of "whistleblower." This term encompasses a complex reality: it represents the honour and integrity that come with standing up for truth and justice while also carrying the burden of stigma and potential personal consequences, such as workplace retaliation or social ostracism.

In this challenging context, a crucial question arises: Should we celebrate and support those who risk their security and reputation to expose misconduct, thereby fostering a culture of accountability and transparency? Or should we condemn their actions, viewing them as threats to stability and order? The answer to this question can significantly influence the ethics of openness within our communities and shape how society values integrity versus conformity. Ultimately, creating an environment that supports whistleblowers may be essential for nurturing a just and equitable society.

We are in the process of developing twelve captivating chapters, numbered from 1 to 12, for an upcoming documentary that promises to engage and inform. Each chapter is undergoing meticulous refinement to enhance the speech patterns, ensuring that the narrative flows smoothly and resonates with our audience. The statements presented in these chapters have been rigorously edited and verified for factual accuracy, providing a solid foundation that does not require further revision.

To bring our story to life, we will enrich each chapter with evocative images that capture the essence of the narrative. These visuals will serve to deepen the viewer's understanding and emotional connection to the material. I am committed to completing the image editing process by mid-July 2025, ensuring that every detail is thoughtfully curated. With most chapters already in their final edited form, we are on track to create a cohesive and compelling narrative that will leave a lasting impact.

Chapter 1

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens

Chapter 2

Betrayal deceit disinformation duplicity falsehood fraud hypocrisy lying mendacity treachery and trickery. This sums up the COT government endorsed arbitrations.

Chapter 3

Ending bribery corruption means holding the powerful to account and closing down the systems that allows bribery, illicit financial flows, money laundering, and the enablers of corruption to thrive.

Chapter 4

Learn about government corruption and the dirty deeds used by the government to cover up these horrendous injustices committed against 16 Australian citizens. Government corruption within the public service affected most if not all of the COT arbitrations.

Chapter 5

Corruption is contagious and does not respect sectoral boundaries. Corruption involves duplicity and reduces levels of morality and trust.

Chapter 6

Anti-corruption policies need to be used in anti-corruption reforms and strategy. Corruption metrics and corruption risk assessment is good governance

Chapter 7

Bribery and Corruption happens in the shadows, often with the help of professional enablers such as bankers, lawyers, accountants and real estate agents, opaque financial systems and anonymous shell companies that allow corruption schemes to flourish and the corrupt to launder their wealth.

Chapter 8

Corrupt practices in government and the results of those corrupt practices become problematic enough – but when that corruption becomes systemic in more than one operation, it becomes cancer that endangers the welfare of the world's democracy.

Chapter 9

Corruption in government, including non-government self-regulators, undermines the credibility of that government. It erodes the trust of its citizens who are left without guidance are the feel of purpose. Bribery and Corruption is cancer that destroys economic growth and prosperity.

Chapter 10

The horrendous, unaddressed crimes perpetrated against the COT Cases during government-endorsed arbitrations administered by the Telecommunication Industry Ombudsman have never been investigated.

Chapter 11

This type of skulduggery is treachery, a Judas kiss with dirty dealing and betrayal. This is dirty pool and crookedness and dishonest. This conduct fester’s corruption. It is as bad, if not worse than double-dealing and cheating those who trust you.&a

Chapter 12

Absentjustice.com - the website that triggered the deeper exploration into the world of political corruption, it stands shoulder to shoulder with any true crime story.